You may know this, although the vast majority of Americans — including the media writers, politicians and economists — don’t: Money does not exist in any material form.

Money is nothing more than an electronic notation in an electronic balance sheet. You cannot see, touch, taste, smell, or hear money.

That dollar bill in your wallet is a title to a dollar, telling the world that you own a dollar. Just as a car title is not a car, and a house title is not a house, a dollar bill is not a dollar.

The fact that a dollar has no physical existence is what makes Monetary Sovereignty possible.

Because the U.S. dollar has no physical existence, the U.S. government has the unlimited ability to create infinite dollars at the touch of a computer key.

Within the past twelve months, the government has demonstrated this infinite ability by creating, from thin air, something like SIX TRILLION stimulus dollars, without collecting a single extra dollar in taxes.

The fact that dollars are mere balance sheet numbers makes the following article seem somewhat less shocking than it otherwise would.

Why Would Anyone Buy Crypto Art – Let Alone Spend Millions on What’s Essentially a Link to a JPEG File?

Posted on March 16, 2021 by Yves Smith

By Aaron Hertzmann, Affiliate Faculty of Computer Science, University of Washington. Originally published at The ConversationOn March 11, Beeple, a computer science graduate whose real name is Mike Winkelmann, auctioned a piece of crypto art at Christie’s for US$69 million.

The winning bidder is now named in a digital record that confers ownership. This record, called a nonfungible token, or NFT, is stored in a shared global database.

This database is decentralized using blockchain, so that no single individual or company controls the database.

But “ownership” of crypto art confers no actual rights, other than being able to say that you own the work. You don’t own the copyright, you don’t get a physical print, and anyone can look at the image on the web.

There is merely a record in a public database saying that you own the work – really, it says you own the work at a specific URL.

So why would anyone buy crypto art – let alone spend millions on what’s essentially a link to a JPEG file?

It’s a difficult question, only for those who believe money is a physical thing.

But because money has no physical existence, might just as well ask, “Why would anyone give someone a beautiful, physical automobile, containing 10,000 physical parts, in exchange for numbers in a balance sheet?

Before we try to answer both questions, let’s look a bit further at the article:

Some people buy art for their homes, hoping to incorporate it into their living spaces for pleasure and inspiration.

But art also plays many important social roles. The art in your home communicates your interests and tastes. Artworks can spark conversation, whether they’re in museums or homes.

People form communities around their passion for the arts, whether it’s through museums and galleries, or magazines and websites. Buying work supports the artists and the arts.

Let me tell you three short stories about money, value, and art.

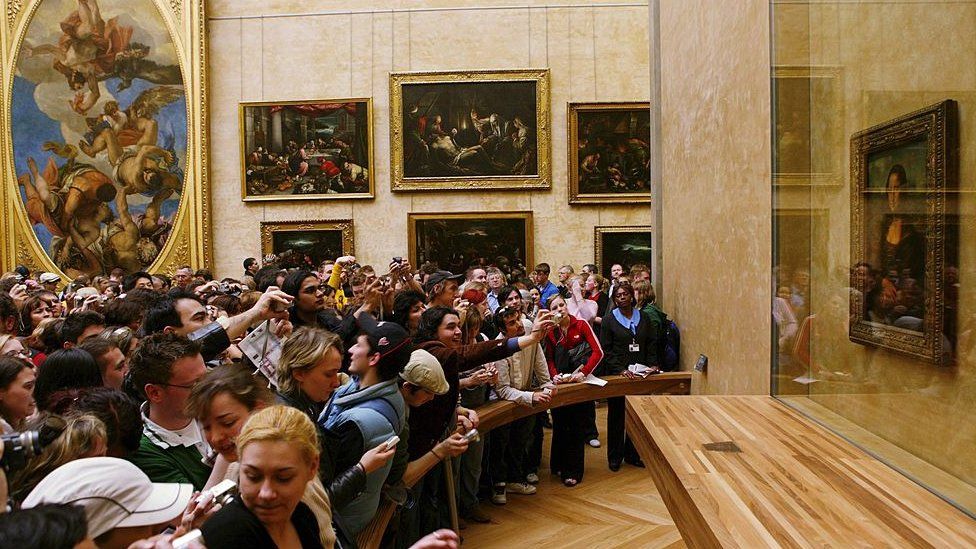

Story #1. Have you been to the Louvre and seen the famous Mona Lisa?

It’s a surprisingly small portrait, and your view is limited by the fact that a rail protects it from a close approach.

Further, most of the time, it is surrounded by a dense crowd of viewers, each of whom is able to spend only a few seconds to look at what arguably is the most famous painting in the world.

In the unlikely event this painting ever were sold, the cost would be in the trillions of euros.

Yet, you could purchase a very good lithographed copy for a few dollars, and you could hang it in your home, and enjoy it for hours on end.

So why would anyone spend millions, billions, or trillions of dollars to own something they could have for next to nothing?

Story #2. Years ago, I bought for my wife (now deceased) a ring, from a cousin (also now deceased) who was a wholesale diamond merchant. He sold to retailers, who sold to the public, so his own buying price was quite low.

The ring had a magnificent center diamond weighing 3 carats, with a diamond on both sides, each weighing 2 carats.

As I recall, the “family” price to me was about $7,000. I since have sold that ring for many times that amount.

But, I could have purchased an essentially identical piece of jewelry, made from cubic zirconia, for about $750, give or take.

Without a jeweler’s loop, no one (but my wife) would have been the wiser.

So why would a fool (me) spend so much on essentially nothing?

Perhaps the most visible form of art collecting today, and the one that drives so much public discussion about art, is the art purchased for millions of dollars – the pieces by Picasso and Damien Hirst traded by the ultrawealthy.

Why were those pieces of are exchanged for so much money?

Finally, I think many people buy art strictly as an investment, hoping that it will appreciate in value.

If you look at the reasons people buy art, only one of them – buying art for your home – has to do with the physical work.

Every other reason for buying art that I listed could apply to crypto art.

You can build your own virtual gallery online and share it with other people online. You can convey your tastes and interests through your virtual gallery and support artists by buying their work.

You can participate in a community: Some crypto artists, who have felt excluded by the mainstream art world, say they have found more support in the crypto community and can now earn a living making art.

While Beeple’s big sale made headlines, most crypto art sales are much more affordable, in the tens or hundreds of dollars. This supports a much larger community than just a select few artists. And some resale values have gone up.

Aside from the visual pleasure of physical objects, nearly all the value art offers is, in some way, a social construct. This does not mean that art is interchangeable, or that the historical significance and technical skill of a Rembrandt is imaginary.

It means that the value we place on these attributes is a choice.

Story #3. It’s not really a story, but a common observation: Millionaires and billionaires love to see their names on things: Hospitals, schools, libraries, sports’ centers, etc. So they give away millions or billions of dollars, just to see what they could have seen for a few dollars or nothing: Their names.

What do they get for their money? Nothing physical.

They could have contributed without insisting that their name be engraved somewhere. They received the same benefit as did the person who bought the crypto art, and the same benefit I received for buying three transparent stones my wife could wear.

And that is the not-so-secret of the balance sheet notation we call “money.” Those arbitrary, non-physical, made-from-thin air dollars have enough value to be traded for . . . traded for what? A couple of transparent stones? A picture?

They all are valuable because we social animals choose to deem them valuable.

You might respond that scarcity is what makes them valuable. But plenty of things are scarce and not valuable. I paint, but my paintings are not valuable, though they are just as scarce as the Mona Lisa.

You might say beauty or artistic talent makes them valuable. But before artists become famous, their paintings are just as beautiful and require just as much talent, but are valued much less.

When someone pays $90 million for a metal balloon animal made by Jeff Koons, it’s hard to believe that the work has that much “intrinsic” value.

Even if the materials and craftsmanship are quite good, surely some of those millions are simply buying the right to say “I bought a Koons. And I spent a lot of money on it.” If you just want an artfully made metal balloon animal, there are cheaper ways to get one.

Conversely, the conceptual art tradition has long separated the object itself from the value of the work. Maurizio Cattelan sold a banana taped to a wall for six figures, twice; the value of the work was not in the banana or in the duct tape, nor in the way that the two were attached, but in the story and drama around the work.

Again, the buyers weren’t really buying a banana, they were buying the right to say they “owned” this artwork.

Depending on your point of view, crypto art could be the ultimate manifestation of conceptual art’s separation of the work of art from any physical object. It is pure conceptual abstraction, applied to ownership.

On the other hand, crypto art could be seen as reducing art to the purest form of buying and selling for conspicuous consumption.

In Victor Pelevin’s satirical novel “Homo Zapiens,” the main character visits an art exhibition where only the names and sale prices of the works are shown. When he says he doesn’t understand – where are the paintings themselves? – it becomes clear that this isn’t the point. Buying and selling is more important than the art.

This story was satire. But crypto art takes this one step further. If the point of ownership is to be able to say you own the work, why bother with anything but a receipt?

The reason art, or anything else — cars, houses, jewelry, etc. — has value is not just its intrinsic value. For most of us, there are cheaper forms of transportation, cheaper forms of shelter, and cheaper stones than what we paid. A scratched and dented car has the same transportation value as does a shiny, untainted car.

We are social animals. These things have value because other people think they have value, and they are willing to exchange other things they think have value to get them.

And that is why money has value.

Money has value because the world thinks it has value. Remember, money has no physical existence. It is just a bookkeeping notation. And that same notation might appear in several places.

It might appear on your bank’s computer, on your computer, or on dozens of other computers. No matter how many computers it appears in, it still is the same money. It still has the same value.

It still seems hard to get used to the idea of spending money for nothing tangible.

Would anyone pay money for NFTs that say they “own” the Brooklyn Bridge or the whole of the Earth or the concept of love? People can create all the NFTs they want about anything, over and over again. I could make my own NFT claiming that I own the Mona Lisa, and record it to the blockchain, and no one could stop me.

But I think this misses the point.

In crypto art, there is an implicit contract that what you’re buying is unique. The artist makes only one of these tokens, and the one right you get when you buy crypto art is to say that you own that work.

Actually, the more important right is to say that you can afford to own the work.

As an investment, crypto-art just seems inconceivable to me that the higher prices reflect true value, in the sense of these works having higher resale value in the long term. As in the traditional art world, there are a lot more works being sold than could ever possibly be considered significant in a generation’s time.

And, in the crypto world, we’re seeing highly volatile prices, a sudden frenzy of interest, and huge sums being paid for things that seem, on the surface, not to have the slightest bit of value at all, such as the $2.5 million bid to “own” Jack Dorsey’s first tweetor even the $1,000 bid on a photo of a cease-and-desist letter about NFTs.

Much of this energy seems to be driven by price speculation. It’s also worth noting that the winner of the Beeple auction seems to be heavily invested in the success of crypto art. The cryptocurrencies that drive crypto art are often considered highly speculative.

Yes, there could be a tulip-bulb bubble at work here. And, where there is no intrinsic value, the possibility of a bubble increases.

But money itself has no intrinsic value. The value of the U.S. dollar is backed by the full faith and credit of the U.S. government. (See: Understanding Federal Debt. Full Faith and Credit.)

But what backs the full faith and credit of the U.S. government. No, not the “amber waves of grain,” or the “purple mountain majesties,” or the “enameled plain.” No creditor can acquire those.

The value of the Mona Lisa, the diamond ring, a mansion, a Rolls Royce car, the full faith and credit of the U.S. government, and the value of the U.S. dollar itself, all are backed by the same thing: Society’s belief that they have value.

Do you believe the dollar, that whispy, non-physical number in a bookkeeping record has value? If so, you are part of the billions of people who also think it has value.

Your dog doesn’t value a dollar. A fish doesn’t value a dollar. Tribes in the Amazon jungle don’t value the dollar.

But billions of people do, simply because other billions of people do. That is how value is determined.

When people claim that the federal government or some agency of the federal government (Social Security, Medicare et al) is in danger of running short of dollars, the ignorance is manifest. How can a government run short of something it creates by waving a magic wand (in the form of a computer key)?

Soon, President Biden will tell us he has to raise taxes in order to “pay for” the trillions being spent for COVID relief. It is utter nonsense. It is terrible, horrible, damaging Big Lie.

It is a lie that punishes America every day, by preventing us from having Medicare for All, Good Education for All, Good Housing for All, Good Food for All, Good Clothing for All, Good Transportation for All, and every other easily affordable (by the federal government) benefit.

The U.S. government not only has the unlimited ability to create dollars from thin air, but it can give those dollars any value it chooses (i.e. prevent or cure inflation.) The government neither borrows nor levies taxes to obtain dollars. It just waves that magic wand.

What is a dollar worth? Whatever its creator and society says it’s worth.

Hey, 69 million of them are worth the ability to claim you own a link to a JPEG file.

And it cost the federal government absolutely nothing to create those 69 million dollars.

In that same vein, if you send me a thousand dollars, I will send you (electronically, of course) a receipt saying you sent me $1,000. You can print it and hang it proudly in your home.

Giving you that receipt will cost me as much as providing free Medicare for All would cost the U.S. government.

Exactly as much.

Rodger Malcolm Mitchell

Monetary Sovereignty Twitter: @rodgermitchell Search #monetarysovereignty Facebook: Rodger Malcolm Mitchell …………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………..

THE SOLE PURPOSE OF GOVERNMENT IS TO IMPROVE AND PROTECT THE LIVES OF THE PEOPLE.

The most important problems in economics involve:

- Monetary Sovereignty describes money creation and destruction.

- Gap Psychology describes the common desire to distance oneself from those “below” in any socio-economic ranking, and to come nearer those “above.” The socio-economic distance is referred to as “The Gap.”

Wide Gaps negatively affect poverty, health and longevity, education, housing, law and crime, war, leadership, ownership, bigotry, supply and demand, taxation, GDP, international relations, scientific advancement, the environment, human motivation and well-being, and virtually every other issue in economics. Implementation of Monetary Sovereignty and The Ten Steps To Prosperity can grow the economy and narrow the Gaps:

Ten Steps To Prosperity:

- Eliminate FICA

- Federally funded Medicare — parts A, B & D, plus long-term care — for everyone

- Social Security for all

- Free education (including post-grad) for everyone

- Salary for attending school

- Eliminate federal taxes on business

- Increase the standard income tax deduction, annually.

- Tax the very rich (the “.1%”) more, with higher progressive tax rates on all forms of income.

- Federal ownership of all banks

- Increase federal spending on the myriad initiatives that benefit America’s 99.9%

The Ten Steps will grow the economy and narrow the income/wealth/power Gap between the rich and the rest.

MONETARY SOVEREIGNTY

Being able to meet all financial obligations is solvency. Maybe we should refer to all of this as Monetary Solvency, since there are no real national borders either, except where land meets water. So Trump was right. If there’s no borders, there’s no states and therefore no sovereignty.

LikeLike

Could not link on to the “Full Faith and Credit URL.

So let’s say the government did pay for a college education. Who would determine what a teacher’s salary should be?

LikeLike

I fixed the link. Thanks for calling my attention to it.

In answer to your question: Use the “Medicare” system, in which a committee determines what Medicare will pay for all procedures. A committee can determine what the government will pay for courses and classes. Individual salaries will be derivative of that.

Alternatively, use the system local governments use for determining what they will pay for grades K-12.

LikeLike