Gap Psychology is the desire to distance oneself from those considered “below” you in any socioeconomic ranking, and to come closer to those above.

You are subject to Gap Psychology, whether you realize it or not.

Think about where you live, who your friends are, where you go to school, the type of job you’ll accept, how you vote, who you marry, and as in the case of the movie, “Parasite,” your relationship with those you employ and those who employ you.

A discussion of Parasite can be found here; some excerpts from that discussion are below:

The Invisible Line

“Parasite” nails the inherent inequality of hiring household help

By Sarah Todd

The South Korean satire-thriller Parasite is emerging as a major contender this awards season.It’s on the Oscars shortlist for best international film, while writer-director Bong Joon-ho received Golden Globe nominations for best director and best screenplay, and the movie’s cast is up for best film ensemble at the Screen Actors Guild awards.

(The movie) focuses on the complex relationships and moral ambiguity that surrounds hiring household help.

For the uninitiated (spoilers ahead!), Parasite tells the story of the Kims, a poor family who connive their way into working (for) the wealthy Parks.

To get on the rich family’s payroll, the Kims must appear more educated and accustomed to rubbing shoulders with the upper class than they actually are.

The son pretends to have a prestigious university degree; the daughter poses as a trained art therapist. The parents invent lengthy employment histories as a highly sought-after driver and housekeeper.

Yet even as the Kims disguise themselves, they must also respect what Mr. Park, the head of the family, refers to repeatedly as “the line”—the boundaries that mark them as employees in a hierarchical relationship, the terms of which are defined exclusively by the Parks.

It’s fine for Mrs. Park to expect the Kims to come to work on their day off to put together a last-minute birthday party for her son. But it’s unacceptable for Mr. Kim to talk too much about himself as he drives his boss home at the end of a long work day.

The Kims may be the wealthy family’s intimates, even confidantes, but they are never to think of themselves as equals.

This dynamic rings true to the real-life experiences of many domestic workers, according to Megan Stack, a journalist and author of the book Women’s Work: A Reckoning With Work and Home.

“Power imbalances tend to manifest most frequently like this,” Stack writes. “The house becomes both an intimate family setting and a job site at the same time. But employers are the ones who have the power, and they end up getting to decide (often without being conscious of it) whether they are approaching the employee in a way that corresponds to an intimate relationship or in a way that corresponds to an employment relationship.

So the employee has to navigate both a faux family relationship and a job where basic labor rights can be granted or withdrawn on the whim of an unreliable manager.”

It’s a job arrangement that depends on a wide gap between haves and have-nots.

Women shouldn’t feel guilty about hiring household help, but that they should push for regulations that ensure domestic workers are earning fair wages and working under non-exploitative conditions.

The movie also exposes the toxicity of the Parks’ expectation that they can pay domestic workers to care for them without caring about the workers in return, or even seeing their employees as fully human.

There is a deep unfairness in the notion that employers get to decide where that line between intimacy and work is drawn—and, usually, it keeps shifting around.

Nannies are asked to be “simultaneously present and absent in children’s lives”—and to be sensitive enough to know when to negate themselves in order to preserve their boss’s feelings.

Parasite makes it impossible for audiences to ignore the uncomfortable ways in which household labor has been constructed to prioritize one group’s emotional life over another—and suggests that money is not all that’s owed to the people who power middle- and upper-class homes.

The income/wealth/power Gap, which stimulates Gap Psychology, always has existed in our lives, always will exist, and indeed must exist in any realistic socio-economic setting. The problem, however, occurs when the Gap becomes too wide, as it always tends to do.

The width of the Gap is determined by the more powerful — i.e., those “above.” Their natural instincts are to widen the Gap, because it is the Gap that makes them superior. (Without Gaps, no one would be superior. We all would be the same.) And the wider the Gaps, the more superior they are.

Thus, over time, a Gap tends to persist or even widen, because that is what the more powerful want.

Then, moral pressure causes a revolution by the lower group and/or an awakening by the upper group.

The Gap temporarily narrows. It becomes “improper” or unlawful. Then, it again begins to widen, as the upper group resumes its resistance.

Typical scenario: A weaker group is bullied by a more powerful group’s leaders. These actions are mimicked by the more powerful group’s followers until the bigotry becomes routine and traditional.

At some tipping point, the bullied group resists and/or the more powerful group’s leaders find virtue, and they declare the bullying to be improper or unlawful.

After a time, some of the more powerful group’s leaders begin to justify and to resume the bullying, and the cycle repeats.

Slavery in America, the Civil War, and its aftermath provide one example. Today, years after blacks received the right to vote, America’s bigots attempt, and often succeed, in making voting more difficult for blacks.

Social Security, launched as a partial cure for poverty, now is under atta ck, as is healthcare and other benefits for the poor.

Another example. I play tennis, and I much prefer to play with those whose skills are at least equal to, and preferably superior to my own. On the surface, this may seem illogical, because I have a much greater chance of winning when I compete with inferior players. Still, I dislike playing with them.

I like to play with the “big boys,” and it doesn’t trouble me at all that the “big boys” may not relish playing with me.

Gap Psychology is everywhere. From your “trophy” (or not-so-trophy) wife, to the size of your house in the “right” neighborhood, to sending your children to the “right” school, to belonging to the “right” club, to your clothing, your jewelry, your car, to having the “right” job, the certificate on your wall, yours and your child’s achievements, to your friends, to being an “A-lister (or not),” even to your accent and the language you use, you live your life guided by Gap Psychology, whether you are willing to admit it or not.

If you are a fan of a team, your emotions watching that team are guided by Gap Psychology. When you see a list of nations, states, or cities, ranked by any positive measure, you want to see your nation, state, or city near the top.

Would you like to be rich? “Rich” is a comparative, not an absolute. You can be rich only if others are poorer. The wider the Gaps below you, the richer you are.

Gap Psychology certainly is not your sole motivator, but it is the single, most powerful motivator in human society, and perhaps in other social animals’ societies, too.

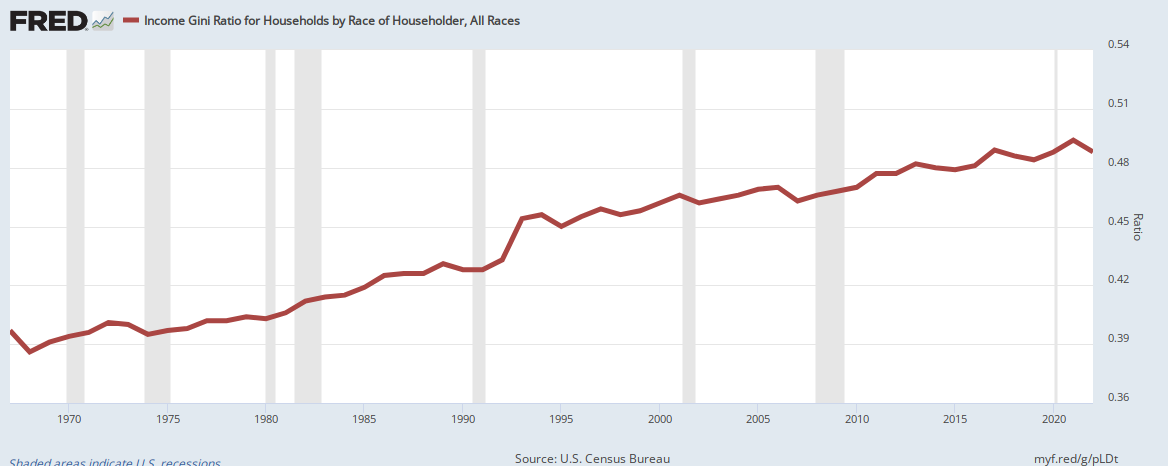

The Gap in America is too wide, and is widening.

But the Gap can be narrowed. Because the U.S. government is Monetarily Sovereign, and so has the unlimited ability to create its own sovereign currency, it also has the unlimited ability to narrow the Gap.

Applying the Ten Steps to Prosperity (below) would narrow the Gap.

Because of Gap Psychology, the very rich do not want the Gap narrowed. But they comprise only 1% of the voting population.

Narrowing the Gap is a job for the 99%. They can’t hope the 1% will save them.

Rodger Malcolm Mitchell

Monetary Sovereignty

Twitter: @rodgermitchell

Search #monetarysovereignty Facebook: Rodger Malcolm Mitchell

…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………..

The most important problems in economics involve:

- Monetary Sovereignty describes money creation and destruction.

- Gap Psychology describes the common desire to distance oneself from those “below” in any socio-economic ranking, and to come nearer those “above.” The socio-economic distance is referred to as “The Gap.”

Wide Gaps negatively affect poverty, health and longevity, education, housing, law and crime, war, leadership, ownership, bigotry, supply and demand, taxation, GDP, international relations, scientific advancement, the environment, human motivation and well-being, and virtually every other issue in economics.

Implementation of Monetary Sovereignty and The Ten Steps To Prosperity can grow the economy and narrow the Gaps:

Ten Steps To Prosperity:

2. Federally funded Medicare — parts A, B & D, plus long-term care — for everyone

3. Provide a monthly economic bonus to every man, woman and child in America (similar to social security for all)

4. Free education (including post-grad) for everyone

5. Salary for attending school

6. Eliminate federal taxes on business

7. Increase the standard income tax deduction, annually.

8. Tax the very rich (the “.1%”) more, with higher progressive tax rates on all forms of income.

9. Federal ownership of all banks

10. Increase federal spending on the myriad initiatives that benefit America’s 99.9%

The Ten Steps will grow the economy and narrow the income/wealth/power Gap between the rich and the rest.

MONETARY SOVEREIGNTY