.

It takes only two things to keep people in chains:

The ignorance of the oppressed

and the treachery of their leaders.

——————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————–

Imagine you have been feeling unusually tired, so you visit your doctor, who performs various tests. Here is the resultant conversation:

Doctor: Based on the results of your tests, you have severe anemia. You don’t have enough healthy red blood cells.

You: What do you recommend?

Doctor: Leeches.

You: But don’t leeches remove blood. How will that help?

Doctor: If you have too many red blood cells, eventually that will cause strokes, heart attacks, embolisms, even death. Excessive red blood cells is not sustainable.

You: But I thought I had too few red blood cells, not too many. Shouldn’t I be taking iron or vitamin B-12 or something?

Doctor. Oh, no. Excessive iron eventually will cause heart attack or heart failure, diabetes mellitus, osteoporosis, hypothyroidism, and a bunch of other symptoms. And too much vitamin B-12 eventually will cause a rare form of acne. Yes, excessive iron and B-12 are not sustainable.

You: When would the adverse effects of adding iron and vitamin B-12 to my diet occur.

Doctor: It’s impossible to say.

You: So what should I do?

Doctor: Leeches.

In summary, your doctor said you have too few red blood cells, then said the usual cures — iron and B-12 — cannot be sustained and will cause many diseases, and instead suggested removing your blood cells via leeches.

Can you draw any parallels with the following excerpt, which essentially expresses the beliefs of today’s economics:

Sustained Budget Deficits: Longer-Run U.S. Economic Performance and the Risk of Financial and Fiscal Disarray

Allen Sinai, Peter R. Orszag, and Robert E. Rubin, Brookings InstituteThe U.S. federal budget is on an unsustainable path. In the absence of significant policy changes, federal government deficits are expected to total around $5 trillion over the next decade.

Such deficits will cause U.S. government debt, relative to GDP, to rise significantly. Thereafter, as the baby boomers increasingly reach retirement age and claim Social Security and Medicare benefits, government deficits and debt are likely to grow even more sharply.

The scale of the nation’s projected budgetary imbalances is now so large that the risk of severe adverse consequences must be taken very seriously, although it is impossible to predict when such consequences may occur.

Let’s pause to examine exactly what a federal deficit is. A federal deficit is the difference between federal tax collections and federal spending.

Thus, a federal deficit is the net number of dollars the federal government adds to the economy, aka the “private sector.”

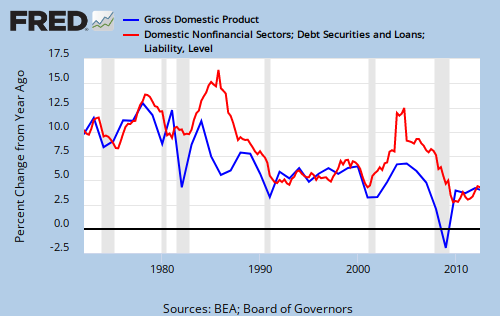

Dollars are the lifeblood of our economy. Our economic growth is measured in dollars. Gross Domestic Product (GDP) is our usual economic measure; it is a dollar measure.

Because GDP is a dollar measure, GDP rarely can grow while the dollar supply is falling

The graph below shows the essentially parallel paths of GDP growth vs. perhaps the most comprehensive measure of the dollar supply growth, Domestic Non-Financial Debt:

Because deficits and GDP growth go hand-in-hand, why do conventional economists argue against deficits? What are the “severe adverse consequences” to which the authors refer?

Again from the Brookings article, here is what the “science” of economics tells you:

Conventional analyses of sustained budget deficits demonstrate the negative effects of deficits on long-term economic growth.

This is what economists say, though the facts speak otherwise, as you easily can see from the above graph.

What school of thought deliberately ignores easily obtainable facts in favor of intuitive belief? No, not science. Religion.

Economics is a religion, dressed in the clothing of a science.

Under the conventional view, ongoing budget deficits decrease national saving, which reduces domestic investment and increases borrowing from abroad.

The authors make the amazing claim that adding dollars to the private sector reduces domestic investment. How giving dollars to consumers and to businesses can reduce investment, never is explained, simply because it makes no sense, whatsoever.

. . . and increases borrowing from abroad.

Obviously, adding dollars to the private sector will not cause you or your business to borrow, so we assume the authors mean the federal government will have to borrow.

But the federal government is Monetarily Sovereign. It has the unlimited ability to create brand new dollars, ad hoc, every time it pays a creditor. It never can run short of dollars, unintentionally.

Not only does the federal government (unlike state and local governments, which are monetarily non-sovereign) not need to borrow, but indeed it does not borrow.

Those T-securities (T-bonds, T-notes, T-bills) which supposedly are evidence of borrowing, actually are evidence of accepting deposits in T-security accounts — similar to bank savings accounts.

The government issues T-securities, not to obtain those dollars it can create forever, but rather to help control interest rates, to provide safe dollar investments, and to provide a basis for the dollar being the world’s reserve currency.

The article then follows with pseudo-scientific gobbledegook, which I will try to explain:

Interest rates play a key role in how the economy adjusts. The reduction in national saving raises domestic interest rates, which dampens investment and attracts capital from abroad.

The Fed, not national saving, arbitrarily controls interest rates via the Fed funds rate. Actually, it is interest rates that increase saving rather than the other way around. Capital coming in from abroad is economically stimulative — a good thing.

The external borrowing that helps to finance the budget deficit is reflected in a larger current account deficit, creating a linkage between the budget deficit and the current account deficit.

The reduction in domestic investment (which lowers productivity growth) and the increase in the current account deficit (which requires that more of the returns from the domestic capital stock accrue to foreigners) both reduce future national income, with the loss in income steadily growing over time.

But, wait. The authors express a concern about the “loss of future national income, ” meaning the economy will lose dollars.

But losing dollars is exactly what happens to the economy when the federal government runs a surplus. It is a federal deficit that adds dollars to the economy.

In short, conventional economists decry deficits that add dollars to the economy, while simultaneously decrying deficits they claim will subtract dollars from the economy.

This is science?

The authors of the article then go off on a magical mystery tour of what deficits will cause:

Substantial ongoing deficits may severely and adversely affect expectations and confidence, which in turn can generate a self-reinforcing negative cycle among the underlying fiscal deficit, financial markets, and the real economy:

-

As traders, investors, and creditors become increasingly concerned that the government would resort to high inflation to reduce the real value of government debt.

The common, nonsense idea is that inflation makes debt easier to pay with cheaper dollars. But so-called federal “debt” consists of T-security deposits, which the government pays off by simply transferring the dollars that exist in T-security accounts back to the checking accounts of T-security holders.

Whether, at the time of redemption, a dollar is “worth” $10 or $0.01 is completely irrelevant. Existing dollars, whatever their worth, are transferred. Period.

-

The fiscal and current account imbalances may also cause a loss of confidence among participants in foreign exchange markets and in international credit markets, as participants in those markets become alarmed not only by the ongoing budget deficits but also by related large current account deficits.

First, to clarify the gobbledegook, there may be a loss of confidence in a certain currency, but there never is a loss of confidence in “foreign exchange markets.”

Foreign exchange rates are determined by inflation, which in turn, is determined by interest rates and by product scarcity. When a nation raises its interest rates, it increases the demand for its currency. It is said to have “strengthened its currency.”

The U.S. has the financial ability to strengthen or weaken its currency at will, or simply to determine exchange rates at will.

- The increase of interest rates, depreciation of the exchange rate, and decline in confidence can reduce stock prices and household wealth, raise the costs of financing to business, and reduce private-sector domestic spending.

Apparently, there are different levels of gobbledegook, because this last paragraph has reached a higher level yet.

“The increase of interest rates” and the “depreciation of the exchange rate” are exact opposites. The effect of increasing interest rates is to increase exchange rates. It’s like saying that increases of demand reduce prices. Total nonsense.

An increase in rates can reduce stock prices, but this does not “reduce household wealth.” Average household wealth is more associated with the total money supply (which is increased by federal deficits), and by the Gap between the rich and the rest (which is narrowed by deficit spending, especially on social programs.)

Incredibly, subsequent paragraphs exceed prevous gobbledegook standards. Here are a few of the “Henny Penny, the sky is falling” excerpts:

- The disruptions to financial markets may impede the intermediation between lenders and borrowers

- . . . potentially substantial increases in interest rates

- . . . become relatively illiquid

- . . . adversely affects the balance sheets of banks and other financial intermediaries;

- . . . reduce business and consumer confidence

- . . . discourage investment and real economic activity

- . . . worsen the fiscal imbalance

- . . . harmful impacts on the economy

- . . . substantially magnify the costs

- . . . asymmetries in the political difficulty of revenue increases and spending reductions

Oh, the list of problems goes on and on, and yet even a modest bit of scientific research shows these problems absolutely do not happen. How can we be so sure?

History.

Back in 1940, when the Henny Penny’s claimed the federal debt was a “ticking time bomb,“ the debt was $40 Billion. And every year thereafter, authors of “learned,” scientific, economics publications have used the “ticking time bomb” example or something similar, to “prove” the federal debt and deficit are “unsustainable.

Today, the federal debt has grown to $14 TRILLION, and we still are sustaining. The ticking time bomb still is ticking, and economists, having learned nothing, still write the same ridiculous articles.

Science changes because of discoveries. Read almost any science book from 100 years ago, and you will find it substantially out of date. And 100 years from now, today’s science books will be obsolete.

What does not change? Religion. The Torah, the Christian Bible, the Koran, all remain quite similar to what they were 100 years ago or 1000 years ago, with only the most minor of linguistic adjustments.

While science is based on evidence, religion is based on belief.

And that is why economics, as currently practiced, is a religion, or at best, a failed science, akin to astrology, phrenology, creationism, homeopathy and a tin foil hat.

Sadly, today, tomorrow, and in the future, you will continue to read the same anti-science about the federal debt. The religious are a stubborn people.

Rodger Malcolm Mitchell

Monetary Sovereignty

Twitter: @rodgermitchell; Search #monetarysovereignty

Facebook: Rodger Malcolm Mitchell

===============================================================================================================================================================

•All we have are partial solutions; the best we can do is try.

•Those, who do not understand the differences between Monetary Sovereignty and monetary non-sovereignty, do not understand economics.

•Any monetarily NON-sovereign government — be it city, county, state or nation — that runs an ongoing trade deficit, eventually will run out of money no matter how much it taxes its citizens.

•The more federal budgets are cut and taxes increased, the weaker an economy becomes..

•No nation can tax itself into prosperity, nor grow without money growth.

•Cutting federal deficits to grow the economy is like applying leeches to cure anemia.

•A growing economy requires a growing supply of money (GDP = Federal Spending + Non-federal Spending + Net Exports)

•Deficit spending grows the supply of money

•The limit to federal deficit spending is an inflation that cannot be cured with interest rate control. The limit to non-federal deficit spending is the ability to borrow.

•Until the 99% understand the need for federal deficits, the upper 1% will rule.

•Progressives think the purpose of government is to protect the poor and powerless from the rich and powerful. Conservatives think the purpose of government is to protect the rich and powerful from the poor and powerless.

•The single most important problem in economics is the Gap between the rich and the rest.

•Austerity is the government’s method for widening the Gap between the rich and the rest.

•Everything in economics devolves to motive, and the motive is the Gap between the rich and the rest..

MONETARY SOVEREIGNTY

From: Sanders Institute

Friend,

Both the House and the Senate have passed versions of a GOP tax plan. According to analyses from the Tax Policy Center, the CBO and numerous economists, both plans overwhelmingly benefit the wealthiest people in this country, and both will result in the loss of health insurance for some 13 million Americans.

Meanwhile, research warns that millions will face higher taxes and a spike in their health insurance premiums in the years ahead. And there isn’t a single credible study that supports the claim that either of these tax plans will deliver the kind of economic growth — with higher wages and substantially more jobs — the GOP is touting to sell their plan.

In response to a plethora of criticism, and to defend their wild growth projections, Republicans recently circulated a letter, claiming to show that the economic community was backing their plan.

What you may not know is that this letter was put together by a corporate advocacy group called the RATE Coalition and, as it turns out, some of the 137 signatories weren’t even economists.

A portion of their letter reads: “Economic growth will accelerate if the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act passes, leading to more jobs, higher wages, and a better standard of living for the American people.”

Let us be clear. This is not what most economists believe. Tax cuts that create economic growth start at the bottom, not at the top.

That is why my colleagues, John T. Harvey, Fadhel Kaboub, and I drafted our own statement and circulated it among professional economists. In the last 48 hours, more than 200 Ph.D. economists have added their names to our open letter.

We hope that you will read what we have to say and pass along our message. It’s not too late to make the current bill into something that could deliver on the promise of more robust growth, high wages and a new era of prosperity for all Americans.

Thank you for staying engaged,

Stephanie Kelton, Professor of Public Policy and Economics at Stony Brook University, and Sanders Institute Founding Fellow

…………………………………………………………………………………………………………..

December 4, 2017

An Open Letter to the U.S. Congress

The tax plan will have disastrous consequences for the American people

Dear Senators and Representatives:

The current tax plan will prove ineffective at best. More likely, it will further the collapse of wages and widen the already dangerous levels of income and wealth inequality that have become so obvious that both political parties referenced them during the 2016 presidential campaign.

Our central problem is not insufficient profits for corporations. Consumers, not employers, are the real job creators and cutting the corporate tax rate won’t jumpstart the economy.

The key to getting businesses to hire and invest is to swamp them with demand for their products, something that is accomplished by raising the incomes of the poor and the middle-class and not those at the very top of the income distribution.

Unfortunately, not only have the former faced stagnating wages and unemployment, but they are burdened by mortgage debt, credit card debt, student debt, and payday loan debt. Little wonder this has been the weakest recovery in the post-World War Two era.

Cut taxes for the poor and the middle class and we will see an increase in wages and the creation of the kind of full-time jobs that we so desperately need.

Cut corporate tax rates and corporations will end up sitting on an even bigger stockpile of cash. Period. There is no reason to believe that any jobs would come back to the United States or that more funds would be invested here.

Firms invest because they expect strong demand for their products, not simply because they have higher profits. Strong demand will only materialize if consumers are empowered with higher wages and relieved of their debt burden.

We, the undersigned economists, stand firmly opposed to the President’s tax plan. Reforms of some sort are not unwarranted, but if our goal is to improve the lives of American workers then this is absolutely not the route to take.

Indeed, it may prove to be disastrous. Tax cuts that create economic growth start at the bottom, not at the top.

It is not too late to make the current bill into something that could spur growth and employment and usher in a new era of prosperity for all Americans.

Sincerely,

John T. Harvey, Professor of Economics, Texas Christian University, TX; Stephanie Kelton, Professor of Public Policy and Economics, Stony Brook University, NY;

Fadhel Kaboub, Associate Professor of Economics, Denison University, OH; James K. Galbraith, Lloyd M. Bentsen Jr. Chair in Government/Business Relations and a Professorship of Government, the LBJ School of Public Affairs, University of Texas, Austin, TX; Aaron Pacitti, Associate Professor of Economics and the Douglas T. Hickey Chair in Business, Siena College, NY; Agnes Quisumbing, PhD Economics, Senior Research Fellow at International Food Policy Research Institute, Washington DC; Alan Aja, Associate Professor and Deputy Chairperson Puerto Rican and Latino Studies, Brooklyn College, NY; Alexander Binder, Assistant Professor of Economics, Finance & Banking, Pittsburg State University, KS; Alexandra Bernasek, Sr. Associate Dean & Professor of Economics, Colorado State University, CO; Alfonso Flores-Lagunes, Professor of Economics, Syracuse University, NY; Allison Shwachman Kaminaga, PhD, Lecturer in Economics, Bryant University, MA; Andrew Barenberg, Assistant Professor of Economics, St. Martin’s University, WA; Andrew Larkin, Emeritus Professor of Economics, St Cloud State University, MN; Anita Dancs, Associate Professor of Economics, Western New England University, MA; Antonio Callari, Professor of Economics, Franklin and Marshall College, PA; Antonio J. Fernós-Sagebien, PhD Economist; Arthur MacEwan, Professor Emeritus of Economics, University of Massachusetts Boston, MA; Avanti Mukherjee, Assistant Professor of Economics, SUNY Cortland, NY; Avraham Baranes, Assistant Professor of Economics, Rollins College, FL; Baban Hasnat, Professor of Economics, The College of Brockport, SUNY, NY; Barbara Wiens-Tuers, Associate Professor of Economics Ermerita, Penn State Altoona, PA; Bernard Smith, Associate Professor of Economics, Drew University, NJ; Brian Werner, PhD Economist at USDA; Bruce Pietrykowski, Professor of Economics, University of Michigan at Dearborn, MI; Cameron Ellis, Assistant Professor of Economics, Temple University, PA; Carol Scotton, Associate Professor of Economics, Knox College, IL; Charalampos Konstantinidis, Assistant Professor of Economics, University of Massachusetts at Boston, MA; Charles Becker, Research Professor of Economics, Duke University, NC; Charu Charusheela, Professor, Interdisciplinary Arts and Sciences, University of Washington, Bothell, WA; Chiara Piovani, Assistant Professor of Economics, University of Denver, CO; Chris Tilly, PhD in Economics and Urban Studies and Planning, Professor of Urban Planning at UCLA, CA; Christopher Brown, Professor of Economics, Arkansas State University, AR; Clara Mattei, Assistant Professor of Economics, New School for Social Research, NY; Dale Tussing, Professor Emeritus of Economics, Syracuse University, NY; Dania Francis, Assistant Professor of Economics, University of Massachusetts at Amherst, MA; Daniel Lawson, Professor of Economics, Oakland Community College, MI; Daniele Tavani, Associate Professor of Economics, Colorado State University, CO; Daphne Greenwood, Professor of Economics, University of Colorado, Colorado Springs, CO; Darrick Hamilton, Associate Professor of Economics and Urban Policy at The Milano School of International Affairs, Management and Urban Policy and the Department of Economics, New School for Social Research, NY; David Eil, Assistant professor of Economics, George Mason University, VA; David Zalewski, Professor of Economics, Providence College, RI; Dell Champlin, PhD economist, Instructor of Economics, Oregon State University, OR; Devin T. Rafferty, Assistant Professor of Economics and Finance, Saint Peter’s University, NJ; Don Goldstein, Emeritus Professor of Economics, Allegheny College, PA; Dorene Isenberg, Professor of Economics, University of Redlands, CA; Douglas Bowles, Assistant Director, Center for Economic Information, University of Missouri at Kansas City, MO; Edith Kuiper, Assistant Professor of Economics, SUNY New Paltz, NY; Edward J Nell, Emeritus Professor, New School for Social Research, NY, and Vice-President, Henry George School of Social Science, Chief Economist, RECIPCO Corp; Eiman Zein-Elabdin, Professor of Economics, Franklin & Marshall College, PA; Elaine McCrate, Associate Professor of Economics and Women’s and Gender Studies, University of Vermont, VT ; Elba Brown-Collier, PhD Economist; Elhussien Mansour, PhD Economist, Senior Financial Analyst, Royal Consulate General of Saudi Arabia, NY; Elizabeth Ramey, Associate Professor of Economics at Hobart and William Smith Colleges, NY; Emily Blank, Associate Professor of Economics, Howard University, Washington DC; Ellis Scharfenaker, Assistant Professor of Economics, University of Missouri – Kansas City, MO; Enid Arvidson, Ph.D. economist, Associate Professor, College of Architecture, Planning and Public Affairs, University of Texas at Arlington, TX; Eric Tymoigne, Associate Professor of Economics at Lewis and Clark College, Portland, OR; Erik Dean, Ph.D., Instructor of Economics, Portland Community College, OR; F. Gregory Hayden, Professor of Economics (retired), University of Nebraska-Lincoln, NE; Farida Khan, Professor of Economics, University of Wisconsin at Parkside, WI; Fatma Gul Unal, Assistant Professor of Economics, Hobart and William Smith Colleges, NY; Firat Demir, Associate Professor of Economics, University of Oklahoma Norman, OK; Flavia Dantas, Associate Professor of Economics, SUNY Cortland, NY; Frank McLaughlin, Associate Professor of Economics (retired), Boston College, MA; Fred Moseley, Professor of Economics at Mount Holyoke College, MA; Frederic Jennings, PhD economist, Economic Consultant, MA; Gary Mongiovi, Associate Professor of Economics and Finance, St. John’s University, NY; Geoffrey Schneider, Professor of Economics, Bucknell University, PA; George DeMartino, PhD economist, Professor at the Josef Korbel School of International Studies, University of Denver, CO; Gerald Epstein, Professor of Economics, University of Massachusetts Amherst, MA; Glen Atkinson, Foundation Professor of Economics Emeritus, University of Nevada, Reno, NV; Haider A. Khan, John Evans Distinguished University Professor, Professor of Economics, University of Denver, CO; Haimanti Bhattacharya, Associate Professor of Economics, University of Utah, UT; Haydar Kurban, Associate Professor of Economics, Howard University, Washington DC; Hector Saez, PhD Economist, Faculty in Community Economic Development, Chatham University, PA; Howard Stein, Professor in the Department of Afroamerican and African Studies (DAAS) and the Department of Epidemiology at the University of Michigan, MI; Hyun Woong Park, Assistant Professor of Economics, Denison University, OH; Ilene Grabel, Professor of Economics in the Josef Korbel School of International Studies at the University of Denver, CO; James G. Devine, Professor of Economics, Loyola Marymount University, CA; James Sturgeon, Professor of Economics, University of Missouri – Kansas City, MO; Jeffrey S. Zax, Professor of Economics, University of Colorado Boulder, CO; Jennifer Olmsted, Professor of Economics, Drew University, NJ; Jim Peach, Regents and Chevron Endowed Professor of Economics, Applied Statistics, and International Business, New Mexico State University, NM; Joelle Leclaire, Associate Professor of Economics and Finance, SUNY Buffalo State, NY.; Johan Uribe, Assistant Professor of Economics, Denison University, OH; John Dennis Chasse, PhD Economist; John Hall, Professor of Economics, Portland State University, OR; John F. Henry, Professor of Economics (retired), California State University, Sacramento, CA; John Sarich, Economist at New York City Department of Finance and Cooper Union, NY; John Willoughby, Professor of Economics, American University, Washington DC; Jon Wisman, Professor of Economics at American University, Washington DC; Jonathan Cogliano, Assistant Professor of Economics, Dickinson College, PA; Jonathan Millman, Lecturer in Economics at University of Massachusetts at Boston, MA; Jonathan Wight, Professor of International Economics, University of Richmond, VA; Jose Caraballo, Assistant Professor of Economics, University of Puerto Rico, PR; Joseph Vavrus, Assistant Professor of Economics, University of Redlands, CA; Julie Nelson, Professor of Economics at the University of Massachusetts Boston, MA; Julio Huato, Associate Professor of Economics, Francis College, NY; June Lapidus, Associate Professor of Economics, Roosevelt University, IL; Karl Petrick, Assistant Professor of Economics, Western New England University, MA; Katherine Moos, Assistant Professor of Economics at the University of Massachusetts Amherst and Economist at the Political Economy Research Institute, MA; Kazim Konyar, Professor of Economics, California State University, San Bernardino, CA; Kimberly Christensen, Professor of Economics, Sarah Lawrence College, NY; Korkut Erturk, Professor of Economics, University of Utah, UT; Lance Taylor, Arnhold Professor Emeritus, New School for Social Research, NY; Laurence Krause, Associate Professor and Chair of Economics, SUNY Old Westbury, NY; Laurie DeMarco, Principal Economist Federal Reserve System, Washington DC; Leanne Roncolato, Assistant Professor of Economics, Franklin and Marshall College, PA; Linda Loubert, Associate Professor and Interim Chair of Economics at Morgan State University; Linwood Tauheed, Associate Professor of Economics, University of Missouri-Kansas City, MO; Lorenzo Garbo, Professor of Economics, University of Redlands, CA; Maggie R. Jones, Economist at US Census, Washington DC; Maliha Safri, Associate Professor of Economics, Drew University, NJ; Marc Tomljanovich, Professor of Economics and Business, Executive Director of Business Programs, Director, Wall Street Semester Program, Drew University, NJ; Marilyn Power, Professor Emerita of Economics, Sarah Lawrence College, NY; Mark Maier, Professor of Economics, Glendale Community College, CA; Mark Paul, Postdoctoral Associate at the Samuel DuBois Cook Center on Social Equity, DukeUniversity, NC; Mark Setterfield, Professor of Economics, New School for Social Research, NY; Marlene Kim, Faculty Staff Union President and Professor Department of Economics, University of Massachusetts Boston, MA; Mary King, Professor of Economics, Portland State University, OR; Mathew Forstater, Professor of Economics, University of Missouri Kansas City, MO; Mayo Toruno, Professor Emeritus, California State University, San Bernardino, CA; Mehrene Larudee, Associate Professor of Economics, Hampshire College, MA; Michael Hudson, Professor of Economics, University of Missouri in Kansas City, MO, and Research Scholar at the Levy Economics Institute of Bard College, NY; Michael J. Murray, Associate Professor of Economics, Bemidji State University, MN; Michael Meeropol, Professor of Economics (retired), Wester New England University, MA; Michael Nuwer, Professor of Economics, SUNY Potsdam, NY; Michalis Nikiforos, Research Scholar at the Levy Economics Institute, NY; Mitch Green, PhD economist, Bonneville Power Administration, OR; Mona Ali, Assistant Professor of Economics, SUNY New Paltz, NY; Nancy Bertaux, Professor of Economics & Sustainability, Xavier University, OH; Nancy Folbre, Professor Emerita of Economics at the University of Massachusetts Amherst, MA; Nancy Rose, Professor of Economics, California State University, San Bernardino, CA; Nasrin Shahinpoor, Professor of Economics, Hanover College, IN; Nathaniel Cline, Assistant Professor of Economics, University of Redlands CA; Neva Goodwin, Co-Director of the Global Development And Environment Institute, Tufts University, MA; Nicholas Reksten, Assistant Professor of Economics, University of Redlands, CA; Nicholas Shunda, Associate Professor of Economics, University of Redlands, CA; Nina Banks, Associate Professor of Economics, Bucknell University, PA; Nurul Aman, Senior Lecturer in Economics, University of Massachusetts at Boston, MA; Omar S. Dahi, Associate Professor of Economics, Hampshire College, MA; Patrick Walsh, Associate Professor of Economics, St. Michael’s College, VT; Paul Smolen, Vice President Fox Smolen and Associates (formerly economist at the Public Utility Commission of Texas), TX; Paula Cole, Teaching Assistant Professor of Economics, University of Denver, CO; Pavlina R. Tcherneva, Chair and Associate Professor of Economics, Bard College, NY; Peter Bohmer, Economics Faculty, Evergreen State College, WA; Peter Eaton, Associate Professor of Economics, Director of the Center for Economic; Information, University of Missouri at Kansas City, MO; Peter Dorman, Professor of Political Economy, Evergreen State College, WA; Philip Harvey, Professor of Law and Economics, Rutgers University, NJ; Praopan Pratoomchat, Assistant Professor, School of Business and Economics, University of Wisconsin Superior, WI; Pratistha Joshi, Postdoc Scholar at Global Development and Environment Institute, Tufts University, MA; Radhika Balakrishnan, Professor of Women’s and Gender Studies, Rutgers University, NJ; Raechelle Mascarenhas, Associate Professor of Economics, Willamette University, OR; Ramaa Vasudevan, Associate Professor of Economics, Colorado State University, CO; Randy Albelda, Graduate Program Director and Professor of Economics, and Senior Research Fellow, Center for Social Policy, University of Massachusetts at Boston, MA; Reynold F. Nesiba, Professor of Economics, Augustana University, SD; Richard D. Wolff, Professor of Economics Emeritus, University of Massachusetts, Amherst, MA, and currently visiting Professor in the Graduate Program in International Affairs of the New School University, NY; Richard McGahey, PhD in economics, former Executive Director of the Congressional Joint Economic Committee; Robert Blecker, Professor of Economics, American University, Washington DC; Robert Pollin, Distinguished Professor of Economics and Co-Director of the Political Economy Research Institute, University of Massachusetts-Amherst, MA; Robert Scott III, Professor of Economics and Finance, Monmouth University, NJ; Robin L. Bartlett, Professor of Economics, Denison University, OH; Rodney Green, Professor, Chair and Executive Director, Center for Urban Progress Department of Economics, Howard University, Washington DC; Ross M. LaRoe, Associate Professor of Economics Emeritus, Denison University, OH; Rudiger von Arnim, Associate Professor of Economics, University of Utah, UT; Sarah Jacobson, Associate Professor of Economics, Williams College, MA; Savvina Chowdhury, Ph.D., Economics Faculty, Evergreen State College, WA; Scott Carter, Associate Professor of Economics, University of Tulsa, OK; Scott Fullwiler, Assistant Professor of Economics, University of Missouri at Kansas City, MO; Shaianne Osterreich, Associate Professor of Economics, Ithaca College, NY; Shakuntala Das, Assistant Professor of Economics, SUNY Potsdam, NY; Sheila Martin, Director of the Population Research Center and of the Institute of Portland Metropolitan Studies, Service and Research Centers, Portland State University, OR; Sohrab Behdad, John E. Harris Professor of Economics, Denison University, OH; Spencer Pack, Professor of Economics, Connecticut College, CT; Sripad Motiram, Associate Professor of Economics, University of Massachusetts Boston, MA; Stacey Jones, PhD Economics, Senior Instructor of Economics, Seattle University, WA; Stephanie Seguino, Professor of Economics, University of Vermont, Burlington, VT; Stephen Bannister, Assistant Professor of Economics, University of Utah, UT; Steven Pressman, Professor of Economics, Colorado State University, CA; Sujata Verma, Professor of Economics at Notre Dame de Namur University in Belmont, CA; Susan Feiner, Professor of Economics and Women and Gender Studies, University of Southern Maine, ME; Tara Natarajan, Professor of Economics, St. Michael’s College, VT; Ted Schmidt, Associate Professor of Economics, SUNY Buffalo State, NY; Teresa Ghilarducci, Professor of Economics, New School for Social Research, NY; Thea Harvey-Barratt, Faculty in Economics, Bard College at Simon’s Rock, MA

LikeLiked by 1 person

Good one, that letter.let’s hope fpr some comprehension.

On a slightly different note I believe that the Central Bankers go along with the politicians and nod in agreement with whatever they say, to keep the peace so to speak but they know the reality too.

However when it suits them, the pollies and central bankers have no qualms about spending up big regardless of the rhetoric. They just don’t want Joe Public to get that message and will go to extremes with any policies to deny it.

Take the GFC bailout. None of that shows up in the annual accounts.It would smash them if it did. The bill paid to save the banks etc came to $29TRILLION!

That’s just ONE off-balance sheet sum.

I also have heard that disaster relief is directly forthcoming from the central bank also. Here in Oz the PM said we would give Aceh $2 Billion for tsunami relief after the 2004 earthquake in Indonesia. Same again for bushfires and floods. These are too catastrophic for insurance companies.

There are hundreds of billions spent off balance sheet for the military. A short list was sent to me- including Veterans pensions [21 million recipients] Then the health care costs for them, the Cost of secret operations, the cost of the MENA wars, and so on.

What do you know about all this?

LikeLike

Its too difficult to balance the economy as like the daily balanced diet, the circumstances and public interest never can be fixed!

LikeLike

The two pillars of conservatism are Family Values and Deficit (or Debt) reduction. They are what Republicans stand for.

Family Values are exemplified by the pu**y-grabber and the Alabama child molester the pu**y-grabber supports.

Deficit (or Debt) reduction is exemplified by the trillion dollar GOP tax bills.

O.K., so maybe the Family Values and Deficit (or Debt) reduction pillars have crumbled, and Republicans no longer stand for them.

Now, they stand only for the flag.

LikeLike

Rodger Thank you for this. I will be forwarding to interested parties.

If you dig into the details of this narrative, you will find that the “crowding out” belief is the foundation for the belief in the decrease in national savings, the higher interest rates, and so on. Once this assumption is removed, the entire edifice falls apart.

And if you dig into the nuts and bolts of their belief in “crowding out’ – you find that it boils down to: “In the deficit financing process, the government takes savings from Agent A (in exchange for a T-security) and gives this money to Agent B. Since Agent B typically spends at least part of this payment, there is a reduction overall in non-T-security savings – and therefore “crowding out.”” Sounds logical and heads all nod. However, what this narrative overlooks is that the money Agent B spent ended up with Agent C and so on. It can not be consumed. or “used up”. At the end of the day, the amount of non-Teasury savngs in the overall system is unchanged and crowding out is not possible. And, of course, the increase in T-securities represents an increase in overall private sector savings.

Since this is very straightforward argument, I write to these “mainstream” economists – provide this insight and politely ask “Is this correct? If not, what am I missing”. As you would expect, I usually get silence. Those that do respond to me don’t address the question and instead state their beliefs. When I then kindly ask the latter group to address my question – they then turn silent.

Ny “joke” is that apparently the developed world is being run on an assumption that does not recognize that there are two sides to a transaction!

But we carry on. After all, itt only took one to reveal that the emperor had no clothes . Thanks.

LikeLike

Yes, it’s always a mystery how adding dollars to the economy can “crowd out” anything. The reverse would be that taking dollars out of the economy via increased taxes, somehow would be stimulative.

I guess if the government stopped spending, we would have an economic boom.

LikeLike