The U.S. military has a motto: The difficult we do immediately. The impossible takes a little longer.

I suggest a motto for the science of economics: “The easy we make impossible, but it takes forever.”

I say that because of my 25 years critiquing economics articles, and most recently because of an article titled, “Do Budget Deficits Cause Inflation?”

The answer to the question is, “No, not for Monetarily Sovereign nations,” and the article comes to that “No” conclusion. Except:

- It never differentiates between Monetarily Sovereign governments (which create and control the value and supply of the money they use) and monetarily non-sovereign governments (cities, counties, states, euro nations, nations that use another nation’s currency, and nations that peg their currency to another nation’s currency}.

- It never mentions shortages of critical goods and services, most commonly oil, food, and labor, which are the real causes of inflation.

- It complexifies a straightforward solution: To cure a problem, eliminate the cause of the problem. In the case of inflation, the cause is shortages. To cure inflations, eliminate the shortages.

Here are some examples from “Do Budget Deficits Cause Inflation?”, by Keith Sill.

In 2004, the federal budget deficit stood at $412 billion and reached 4.5 percent of gross domestic product (GDP).

Though not at a record level, the deficit as a fraction of GDP is now the largest since the early 1980s.

Moreover, the recent swing from surplus to deficit is the largest since the end of World War II.

Comment: The deficit as a fraction of GDP is irrelevant to inflation. Federal deficits are beneficial because they add GDP growth dollars to the economy.

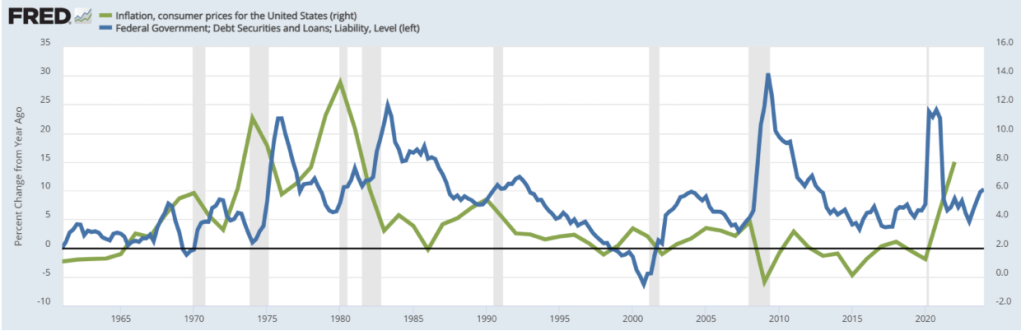

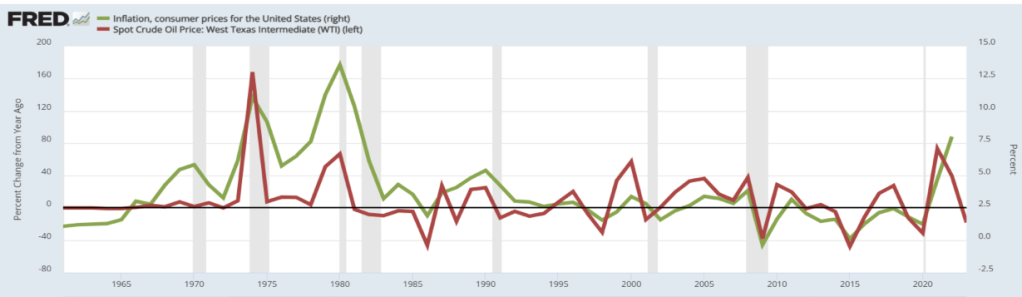

Federal surpluses take dollars from the economy, causing depressions and recessions. Mr. Sill could have answered the title question with two simple graphs:

Inflation is caused by shortages of critical goods and services, most often oil, food, and labor.

The flip side of deficit spending is that the amount of government debt outstanding rises: The government must borrow to finance the excess of its spending over its receipts.

Comment: The federal government, being Monetarily Sovereign, never borrows. Why would it? It has the infinite ability to create its sovereign currency, the U.S. dollar, at virtually no cost (aka, “seigniorage”).

Further, unlike state/local government taxes, which fund state/local spending, federal taxes do not fund federal spending.

Federal taxes are destroyed upon receipt, while state and local tax dollars remain in the economy’s private banks. To finance all its spending, the federal government creates new dollars ad hoc.

It does this regardless of taxes collected. Even if federal tax collection totaled $0, the government could continue spending forever.

For the U.S. economy, the amount of federal debt held by the public as a fraction of GDP has been rising since the early 1970s. It now stands at a little over 37 percent of GDP.

The debt/GDP fraction is meaningless. It has no predictive or analytical power and does not tell anything about an economy’s health.

Do government budget deficits lead to higher inflation? When looking at data across countries, the answer is: it depends. Some countries with high inflation also have large government budget deficits. This suggests a link between budget deficits and inflation.

Yet for developed countries, such as the U.S., which tend to have relatively low inflation, there is little evidence of a tie between deficit spending and inflation.

Mr. Sill falsely equates “developed” with Monetary Sovereignty. However, there are “developed” nations – for example, Italy, France, Greece, etc. that are monetarily non-sovereign. They use the euro.

Why are budget deficits are associated with high inflation in some countries but not in others? Government deficit spending is linked to the quantity of money circulating in the economy through the budget restraint, i.e. the relationship between resources and spending.

Money spent has to come from somewhere: In the case of local and national governments, from taxes or borrowing.

But, national governments can also use monetary policy to help finance the government’s deficits.

I believe that Mr. Sill’s use of “resources” means the amount of money a government can spend, which it gets from taxes or borrowing.

Since he doesn’t differentiate among Monetarily Sovereign, monetarily non-sovereign, and “nationally,” his comments are either partially or totally wrong. First, a reminder about the differences between monetary policy and fiscal policy:

- Monetary policy involves changing the interest rate and influencing the money supply.

- Fiscal policy involves the government changing tax rates and spending levels to influence aggregate economic demand. (“Aggregate demand” is Gross Domestic Product at a specific time.)

Here are the sources of confusion:

1. Raising interest rates causes prices to rise. The cost of every product includes the cost of interest. Amazingly, this is the Fed’s tool to combat inflation. The Fed’s theory seems to be that raising prices will reduce demand, causing a recession that supposedly will cure inflation.

In short, the Fed causes inflation to cure inflation while claiming to hope a recession doesn’t occur but secretly relies on recession to cure inflation. (Clear?)

Of course, a result can also be stagflation, a combination of recession and inflation, at which point Fed Chairman Jerome Powell, having no solutions, will hide in his closet and pray. (The cure for stagflation is federal deficit spending to obtain and distribute the scarce products while adding growth dollars to the economy.)

2. As the issuer of its money, only a Monetarily Sovereign government can change interest rates by fiat. It sets the lowest rate on its Treasury Securities.

Because a monetarily non-sovereign government is not an issuer of money, it cannot unilaterally change interest rates. It must rely on markets or the issuer of its money.

For example, Italy cannot arbitrarily raise interest rates on euro-based loans. It uses the euro but is not the issuer.

3. Monetarily Sovereign governments don’t borrow their own currency. The above-mentioned Italy, being monetarily non-sovereign, borrows euros.

In short, Sill, an economist at the Fed (!), is confused about what different kinds of governments can do. Next, he confuses households with our Monetarily Sovereign government:

Budget constraints are a fact of life we all face. We’re told we can’t spend more than we have or more than we can borrow.

The U.S. government “has” infinite dollars, so it does not borrow dollars. Those federal T-securities are not a form of borrowing, which is what a monetarily non-sovereign government does when it needs money.

Rather than providing the U.S. government with dollars, T-securities:

- Provide a safe parking place for unused dollars — safer than any other storage place (i.e., bank accounts, safe deposit boxes, etc.) The government never touches those dollars. They remain the property of the depositors.

- Assist the Fed in controlling interest rates by setting a floor rate.

In that sense, budget constraints always hold: They reflect the fact that when we make decisions, we must recognize we have limited resources.

See the confusion? “We” and the Italian government have limited resources (money), but the U.S. government does not. It has unlimited money. Next, Mr. Sill expressly shows us his confusion between federal finance and personal finance:

Imagine a household that gets income from working and from past investments in financial assets. The household can also borrow, perhaps by using a credit card or getting a home-equity loan.

The household can then spend the funds obtained from these sources to buy goods and services, such as food, clothing, and haircuts.

It can also use the funds to pay back some of its past borrowing and to invest in financial assets such as stocks and bonds.

The household’s budget constraint says that the sum of its income from working, from financial assets, and from what it borrows must equal its spending plus debt repayment plus new investment in financial assets.

Not one word of the above applies to the U.S. government.

The government does not borrow or use dollars obtained from any source. It creates ad hoc all the funds it spends. Any income the federal government receives is destroyed upon receipt. (See: “Does the U.S. government really destroy your tax dollars?“)

The only federal budget constraint is not a budget constraint at all. Federal agencies routinely exceed budgets. The restraint is whatever Congress and the President say it is at any given moment.

Congress and the President have the unlimited ability to create dollars and stimulate the economy, plus a strong, though not unlimited, ability to obtain and distribute the scarcities causing inflation.

Mr. Sill continues with an explanation that is irrelevant to federal financing.

The household’s sources of funds and spending are all accounted for, and the two must be equal. The household may use borrowing to spend more than it earns, but that funding source is accounted for in the budget constraint.

If the household has hit its borrowing limit, fully drawn down its assets, and spent its work wages, it has nowhere else to turn for funds and would, therefore, be unable to finance additional spending.

I have no idea what Mr. Sills hoped to accomplish by giving household finances as his explanation for federal finances. The two are fundamentally opposite.

Here, Mr. Sills makes sure to show you that he doesn’t understand the difference between the federal government’s Monetary Sovereignty and your household’s monetary non-sovereignty:

Just like households, governments, face constraints that relate spending to sources of funds.

Governments can raise revenue by taxing their citizens, and they can borrow by issuing bonds to citizens and foreigners. In addition, governments may receive revenue from their central banks when new currency is issued.

Governments spend their resources on such things as goods and services, transfer payments such as Social Security to its citizens, and repayment of existing debt.

Central banks are a potential source of financing for government spending, since the revenue the government gets from the central bank can be used to finance spending in lieu of imposing taxes or issuing new bonds.

No, the U.S. government is not “just like households. It does not raise revenue by taxing you. It doesn’t borrow from the central bank. It doesn’t have an existing debt to repay.

And it finances its spending not with taxes or bonds but by creating new money ad hoc. Who says so, Mr. Sill? Your former bosses:

Former Fed Chairman Alan Greenspan: “A government cannot become insolvent with respect to obligations in its own currency. There is nothing to prevent the federal government from creating as much money as it wants and paying it to somebody. The United States can pay any debt it has because we can always print the money to do that.”

Former Fed Chairman Ben Bernanke: “The U.S. government has a technology, called a printing press (or, today, its electronic equivalent), that allows it to produce as many U.S. dollars as it wishes at essentially no cost. It’s not tax money… We simply use the computer to mark up the size of the account.”

Mr. Sill’s article continues for many more paragraphs, so I will just quote one more thought:

There may be limits on the government’s ability to borrow or raise taxes. Obviously, if there were no such limits, there would be no constraint on how much the government could spend at any point in time.

Congress and the president are the only constraints on federal spending. Unlike your checking account, There are no financial constraints. That is why net spending (spending vs. taxing) has risen to $32 trillion.

Certainly governments are limited in their ability to tax citizens. (That is, the government can’t tax more than 100 percent of income.) But are governments constrained in their ability to borrow?

Monetarily non-sovereign governments are constrained by their full faith and credit, i.e., their credit rating. Monetarily Sovereign governments have no need to borrow, so there is no constraint.

Indeed they are. Informally, the value of government debt outstanding today cannot be more than the value of the government’s resources to pay off the debt.

The U.S. government has the infinite ability to pay for anything. Just ask Fed Chairmen Greenspan and Bernanke.

How do governments pay their current debt obligations? One way is for the government to collect more tax revenue than it spends. In this case, the surplus can be used to pay bondholders.

Wrong. All a federal surplus does is reduce Gross Domestic Product, i.e., cause a recession or depression.

Another way to finance existing debt is to collect seigniorage revenue and use that to pay bondholders.

Half right, half wrong. “Collect seigniorage” is a fancy way to say “print money.”

Seigniorage is the difference between the face value of dollars and the cost of creating them, which comes close to zero. However, holders of U.S. Treasury bonds are paid in two ways: Seigniorage pays the interest, and the principal is paid by returning the bondholder’s deposit.

Finally, the government can borrow more from the public to pay existing debt holders.

Wrong again. The federal government does not borrow, though monetarily non-sovereign governments do borrow.

SUMMARY

It is discouraging to read an article written by the Senior Vice President of Research and Director of the Real-Time Data Research Center for the Federal Reserve that displays so little understanding of Monetarily Sovereign finance.

The article claims that federal finance is similar to personal finance, but it does not demonstrate any knowledge of the vast differences.

Cities, counties, states, businesses, and euro nations can run short of money. The federal government cannot, and a key figure in the Federal Reserve seems to not understand that.

The answer to the title question is, “No, deficits do not cause inflation. Inflation is caused by shortages of key goods and services, most often oil, food, and labor.

Deficit spending can cure inflation by paying for scarce goods and services and ending shortages.

Rodger Malcolm Mitchell

Monetary Sovereignty Twitter: @rodgermitchell Search #monetarysovereignty Facebook: Rodger Malcolm Mitchell; MUCK RACK: https://muckrack.com/rodger-malcolm-mitchell

……………………………………………………………………..

The Sole Purpose of Government Is to Improve and Protect the Lives of the People.

MONETARY SOVEREIGNTY

what a pleasure to read your stuff. I live in the south west interior of BC, am an old (very so ) social democrat and you and the whole MMT /Levy institute, Billy Mitchell collections are the voices of sensibility….but of course that’s just a peep in the cacaphonic bullshit of those protecting the financing of operations of private capital, and private objectives.

I have had a few glasses of wine in response to a long article on the Ukrainian conflict, and general fatigue arising from the thought of the lunatic Trump winning the next election and governing the biggest military force on earth about 49 miles south of my home. The sane thought gets a big hurrah from those struggling for good sense. which makes little sense..but there you go.

jh best wishes

LikeLike

Thanks, John. I share your fatigue. I’m 89.

LikeLike