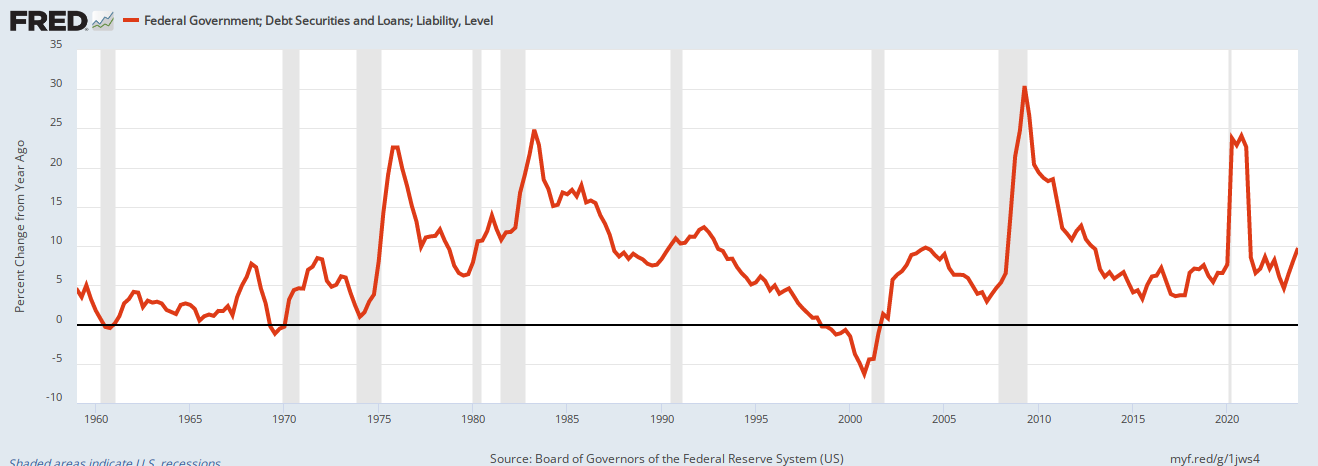

“Worse”? Why is an increase in the so-called “federal debt” (that isn’t federal and isn’t debt) bad? When you read the article, you’ll find that they never say. They just assume it.A million simulations, one verdict for economy: Debt danger ahead Bhargavi Sakthivel, Maeva Cousin, and David Wilcox, Bloomberg News

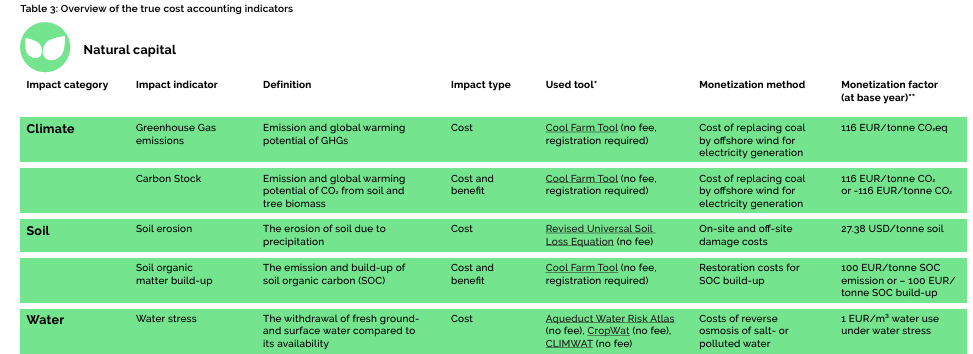

In its latest projections, the Congressional Budget Office warned that U.S. federal government debt will increase from 97% of GDP last year to 116% by 2034—higher than in World War II. The actual outlook is likely worse.

What “burden”? And on whom is the “burden”? Here are seven reasons why the so-called “federal debt” isn’t federal, isn’t debt, and isn’t a burden on anyone. 1. The federal government is Monetarily Sovereign. It has the infinite ability to pay its bills. Even if the government owed the “federal debt,” it instantly could create the dollars to pay it off.Rosy assumptions underpin the CBO forecasts released earlier this year, covering everything from tax revenue to defense spending and interest rates. When you factor in the market’s current view on interest rates, the debt-to-GDP ratio rises to 123% in 2034.

Then assume — as most in Washington do — that ex-President Donald Trump’s tax cuts mainly stay in place, increasing the burden.

Statement from the St. Louis Fed: “As the sole manufacturer of dollars, whose debt is denominated in dollars, the U.S. government can never become insolvent, i.e., unable to pay its bills. In this sense, the government is not dependent on credit markets to remain operational.”

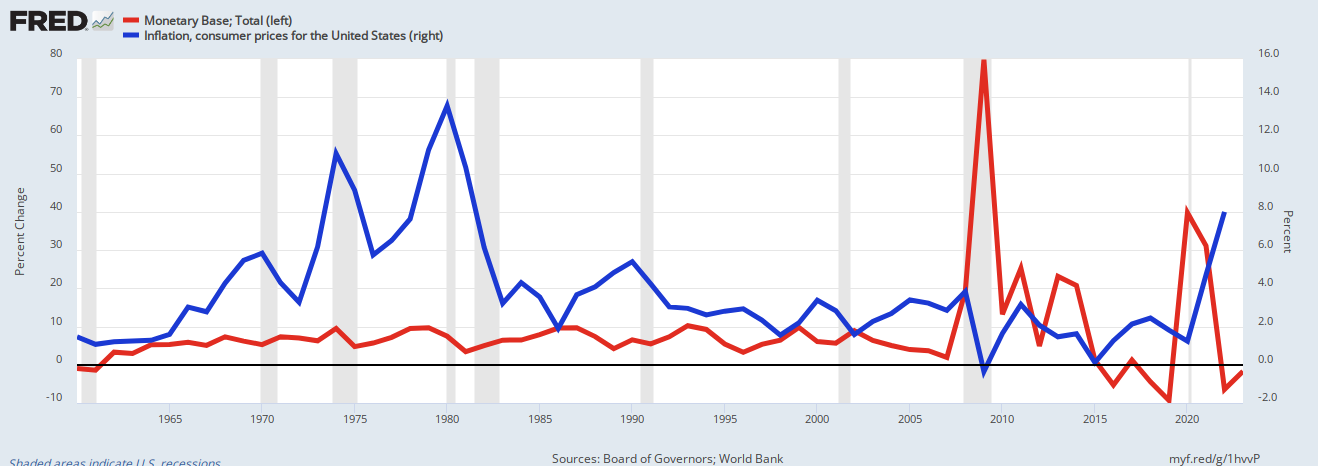

Quote from former Fed Chairman Ben Bernanke when he was on 60 Minutes: Scott Pelley: “Is that tax money the Fed is spending?” Ben Bernanke: “It’s not tax money… We simply use the computer to mark up the size of the account.”

2. The so-called “federal” debt isn’t federal. It is the total of deposits into Treasury Security accounts, the contents of which are wholly owned by the depositors. The federal government doesn’t use those deposits for spending. They sit in the account, earning interest, until maturity, when the government transfers them to the owners’ checking accounts. Because the government doesn’t take ownership of the dollars, the government doesn’t owe the dollars. These accounts resemble bank safe deposit boxes where the contents are not bank debt. They are merely held for safekeeping. Thus, as with safe deposit boxes, the contents of T-security accounts are neither federal nor debt. Even if the “debt” (deposits) were trillions of dollars, that would mean trillions were sitting in Treasury Security accounts, waiting to be returned, which could be accomplished by the touch of a computer key. 3. The debt does not burden the government (it has the infinite ability to pay) or taxpayers (who are never asked to pay for those deposits). 4. The deposits have nothing to do with Gross Domestic Product (GDP), a federal plus non-federal spending measure. Even if the “Debt”/GDP ratio were 100, 1000, or 10,000, this would have nothing to do with the government’s ability to return the dollars in T-Security accounts. If you go to the Debt/GDP ratio by country, you will see a long list of nations and their Debt/GDP ratios. Examine those ratios; you cannot tell anything about the nations’ finances. The ratio says nothing about a nation’s ability to pay what it owes, its economic safety, or its money. It tells you nothing about the past, the present, or the future. It is a classic Apples/Audis comparison, signifying nothing. Sadly, even that country comparison website falsely states, “(The ratio) typically determines the stability and health of a nation’s economy and offers an at-a-glance estimate of a country’s ability to pay back its current debts.” Wrong. The ratio does neither of those things. For a Monetarily Sovereign nation like the U.S., UK, Canada, China, Japan, et al., the ratio says nothing about the stability and health of a nation’s economy or its ability to pay its current debt. Whether federal “Debt” (that isn’t debt) grows faster or slower than GDP means nothing.A normal human being would define “unsustainable” as something that cannot be continued. Apparently, Bloomberg describes it as an increase. “Unsustainable” is a favorite word for “debt” fear-mongers because it absolves them of the requirement to explain what cannot be sustained. The U.S. federal debt has increased from about $40 billion in 1940 to about $30 trillion this year (an astounding 75,000% increase), and fear-mongers have told you it’s a “ticking time bomb.” It has been ticking for 84 years, and still no problems. The prognosticators seem not to learn from failure.With uncertainty about so many variables, Bloomberg Economics has run a million simulations to assess the fragility of the debt outlook. In 88% of the simulations, the results show the debt-to-GDP ratio is unsustainable — defined as an increase over the next decade.

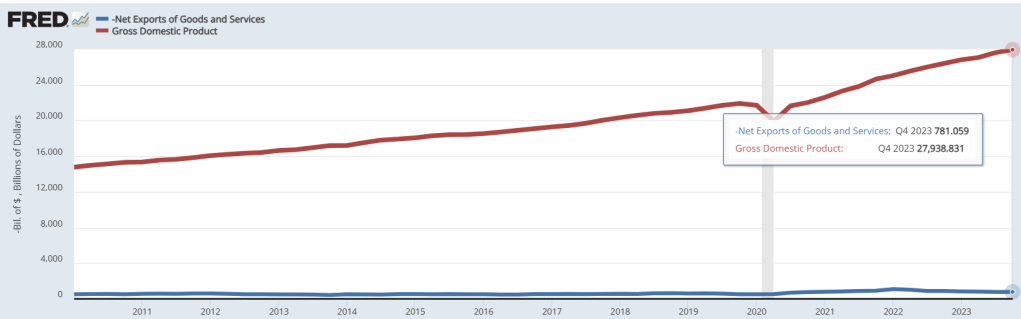

Our Monetarily Sovereign government has infinite fiscal sustainability and can manage any debt-serving costs. In fact, the more interest the federal government pays, the more GDP increases.The Biden administration says its budget, which includes a series of tax hikes on corporations and wealthy Americans, will ensure fiscal sustainability and manageable debt-servicing costs.

GDP=Federal Spending + Nonfederal Spending + Net Exports.

Economic growth benefits from federal interest payments.I do not know why Janet Yellen would promulgate such ignorance or lies. The U.S. has infinite fiscal sustainability and can comfortably pay any interest.“I believe we need to reduce deficits and stay on a fiscally sustainable path,” Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen told lawmakers in February. Biden administration proposals offer “substantial deficit reduction that would continue to hold interest expense at comfortable levels.

But we would need to work together to achieve those savings,” she said.

Alan Greenspan: “A government cannot become insolvent concerning obligations in its own currency. There is nothing to prevent the federal government from creating as much money as it wants and paying it to somebody. The United States can pay any debt it has because we can always print the money to do that.”

To paraphrase the old saying, “There are lies, damned lies, and claims about the federal debt.” Here is what deep spending cuts accomplish:The trouble is that delivering such a plan will require action from a Congress that’s bitterly divided on partisan lines.

Republicans, who control the House, want deep spending cuts to bring down the ballooning deficit without specifying precisely what they’d slash.

Democrats, who oversee the Senate, argue that spending contributes less to debt sustainability deterioration, with interest rates and tax revenues being the key factors.

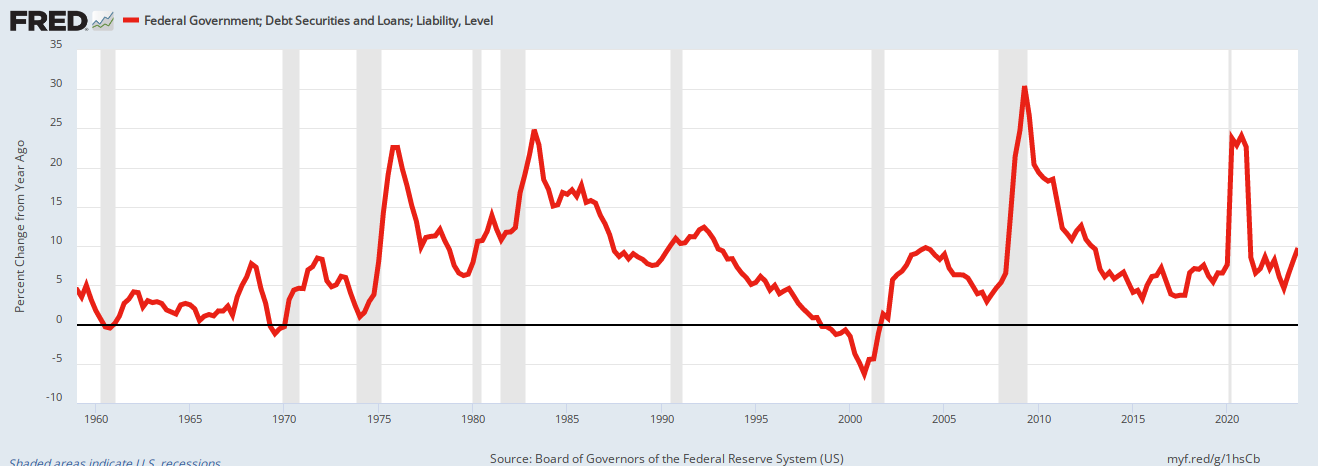

Here is what deficit cuts accomplish:U.S. depressions to come on the heels of federal surpluses. 1804-1812: U. S. Federal Debt reduced 48%. Depression began in 1807. 1817-1821: U. S. Federal Debt reduced 29%. Depression began in 1819. 1823-1836: U. S. Federal Debt reduced 99%. Depression began in 1837. 1852-1857: U. S. Federal Debt reduced 59%. Depression began in 1857. 1867-1873: U. S. Federal Debt reduced 27%. Depression began in 1873. 1880-1893: U. S. Federal Debt reduced 57%. Depression began in 1893. 1920-1930: U. S. Federal Debt reduced 36%. Depression began in 1929. 1997-2001: U. S. Federal Debt reduced 15%. Recession began 2001.

The public understands that federal spending helps the economy. One wonders why the “experts” don’t.Neither party favors squeezing the benefits provided by significant entitlement programs.

The credit-rating agencies have downgraded the U.S. credit, not because of high debt but because Congress threatened not to pay its bills with that ridiculous, useless “debt ceiling.” Congress always has the ability to pay its bills by creating dollars ad hoc. However, credit ratings will fall unnecessarily when Congress threatens creditors due to ignorance or political malevolence.Ultimately, it may take a crisis — perhaps a disorderly rout in the Treasuries market triggered by sovereign U.S. credit-rating downgrades or a panic over the depletion of the Medicare or Social Security trust funds — to force action.

That’s playing with fire.

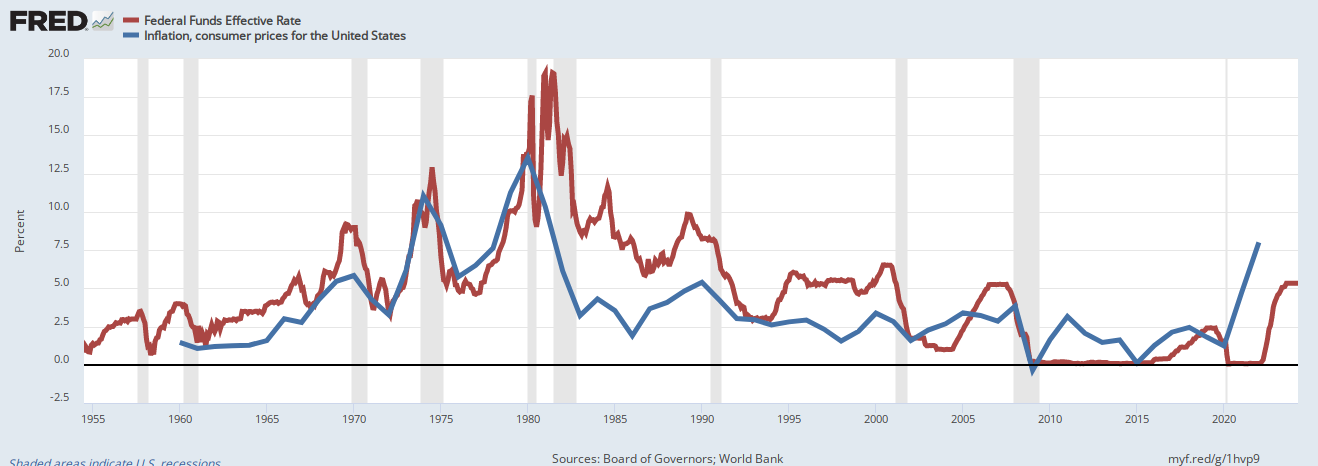

The federal government had no trouble pressing those computer keys that paid the interest. Further, the government didn’t need to pay higher interest; it set the bottom interest rate, and if there was no threat to paying, that will be the rate. For years following the “Great Recession of 2008, federal deficits increased massively, and interest rates stayed near zero. The government and Federal Reserve have the tools to control spending and interest rates.Last summer provided a miniature foretaste of how a crisis might begin. Over two days in August, a Fitch Ratings downgrade of the U.S. credit rating and an increase of long-term Treasury debt issuance focused investor attention on the risks.

Benchmark 10-year yields climbed by a percentage point, hitting 5% in October — the highest level in over a decade.

Yes, “it would take a lot” — a lot more than deficit spending, which, though massive, has not caused the “unsustainability” that the Henny Pennys fret about.Shaking investor confidence in U.S. Treasury debt as the ultimate safe asset would take a lot.

If it evaporated, though, the erosion of the dollar’s standing would be a watershed moment, with the U.S. losing access to cheap financing and global power and prestige.

Hmmm. Extending tax cuts (which allows the private sector to spend more money) would cost 1.2% of GDP each year—strange mathematics.By law, the CBO is compelled to rely on existing legislation. That means it assumes the 2017 Trump tax cuts will expire in 2025. However, even President Joe Biden wants some of them extended.

According to the Penn Wharton Budget Model, permanently extending the legislation’s revenue provisions would cost about 1.2% of GDP each year starting in the late 2020s.

What?? Discretionary spending will increase with inflation but not keep pace with GDP. If I read that correctly, the author warns that GDP will grow faster than inflation. And that’s a bad thing??The CBO also must assume that discretionary spending, which Congress sets each year, will increase with inflation rather than keep pace with GDP.

Borrowing costs are determined by the Fed, which (wrongly) believes raising interest rates (which increases the prices of everything you buy) is a good way to fight inflation! If you can figure that one out, let me know. I can’t.Market participants aren’t buying the benign rates outlook, with forward markets pointing to borrowing costs markedly higher than the CBO assumes.

Which is meaningless.Bloomberg Economics has built a forecast model using market pricing for future interest rates and data on the maturity profile of bonds. Keeping all the CBO’s other assumptions in place shows debt equaling 123% of GDP for 2034.

All it means is that our Monetarily Sovereign government will create more growth dollars and add them to GDP. Is that supposed to be a problem? Mathematically, increases in federal spending increase economic growth.Debt at that level would mean servicing costs reach close to 5.4% of GDP — more than 1.5 times as much as the federal government spent on national defense in 2023, comparable to the entire Social Security budget.

The federal government does not borrow. T-bills, T-notes, and T-bonds do not represent borrowing. They represent deposits into Treasury Security accounts — money the federal government neither needs nor touches. The purpose of those accounts is not to provide spending money to a Monetarily Sovereign government but to provide a safe place to store unused dollars. This stabilizes the dollar.Heavyweights from across the political spectrum agree the long-term outlook is unsettling.

Fed Chair Jerome Powell said earlier this year that it was “probably time—or past time” for politicians to start addressing the “unsustainable” path of borrowing.

Ooooh! “Stochastic sustainability analysis.” And they did it a million times. How many of those times included the fact that the Monetarily Sovereign U.S. government never can run short of dollars to pay its bills and interest? Not yesterday, not today, not tomorrow, not ever? “stochastic” means: “Having a random probability distribution or pattern that may be analyzed statistically but may not be predicted precisely.”Former Treasury Secretary Robert Rubin said in January that the nation is in a “terrible place” regarding deficits.

From the realm of finance, Citadel founder Ken Griffin told investors in a letter to the hedge fund’s investors Monday that the U.S. national debt is a “growing concern that cannot be overlooked.”

Days earlier, BlackRock Inc. Chief Executive Officer Larry Fink said the U.S. public debt situation “is more urgent than I can ever remember.”

Ex-IMF chief economist Kenneth Rogoff says while an exact “upper limit” for debt is unknowable, challenges will arise as the level keeps going up.

Rogoff’s broader point is well taken: forecasts are uncertain. To mitigate this uncertainty, Bloomberg Economics has run a million simulations on the CBO’s baseline view—an approach economists call stochastic debt sustainability analysis.

But the ratio means nothing. It tells you nothing about “sustainability.” More importantly, the proof of abject ignorance comes with those last few words: “crisis-prone Italy.” OMG. They are too ignorant to understand the differences between a Monetarily Sovereign entity and a monetarily non-sovereign entity. Italy is monetarily non-sovereign. It can run short of euros. The U.S. is Monetarily Sovereign. It cannot run short of dollars (unless Congress continues with the foolish debt-limit nonsense.) It’s like claiming that birds can’t fly because elephants can’t fly.Each simulation forecasts the debt-to-GDP ratio with a different combination of GDP growth, inflation, budget deficits, and interest rates, with variations based on patterns seen in the historical data.

In the worst 5% of outcomes, the debt-to-GDP ratio ends in 2034 above 139%, which means the U.S. would have a higher debt ratio in 2034 than crisis-prone Italy did last year.

I assume she’s talking about buyers of T-securities. Surely she knows that:The Treasury chief herself acknowledged in a Feb. 8 hearing that “in an extreme case,” there could be a possibility of borrowing reaching levels that buyers wouldn’t be willing to purchase everything the government sought to sell. She added that she saw no signs of that now.

- The federal government doesn’t need to sell T-securities. They don’t provide the government, as a dollar creator, with anything. They provide dollar users with safe storage.

- If the government had a yen to sell more T-securities, it could always raise interest rates.

This is what ignorance causes. It is an unnecessary battle over a meaningless number to reach a fruitless conclusion. And these are the geniuses we elect to Congress.Getting to a sustainable path will require action from Congress. Precedent isn’t promising. Disagreements over government spending came to a head last summer when a standoff over the debt ceiling brought the U.S. to the brink of default.

The deal to halt the havoc suspended the debt ceiling until Jan. 1, 2025, postponing another clash over borrowing until after the presidential election.

A fictional “debt crisis” (the U.S. federal government unable to create dollars?) has nothing to do with the dollar being the leading “reserve currency.” A reserve currency is just money banks keep in reserve to facilitate international trade. Though the U.S. dollar is a leader, other currencies are reserve currencies, depending on geography: The euro, the Canadian dollar, the Mexican peso, China, Japan, Australia, etc. all produce currencies that banks keep in reserve. There is no magic in being a reserve currency. And it does nothing to prevent a “debt crisis.It’s hard to imagine a U.S. debt crisis. The dollar remains the global reserve currency. The annual and unseemly spectacle of government shutdown brinksmanship typically leaves barely a ripple on the Treasury market.

This has nothing to do with any “debt crisis” or the Debt/GDP ratio.Still, the world is changing. China and other emerging markets are eroding the dollar’s role in trade invoicing, cross-border financing, and foreign exchange reserves.

It’s not federal; it’s not debt, and it’s not a problem.Foreign buyers make up a steadily shrinking share of the U.S. Treasuries market, testing domestic buyers’ appetite for ever-increasing volumes of federal debt.

The federal government doesn’t need to issue T-securities. It creates all its dollars by spending them. The spending comes first, and then it creates dollars.And while demand for those securities has lately been supported by expectations for the Fed to lower interest rates, that dynamic won’t always be in play.

Given that the U.S. government has the infinite ability to create dollars, the endless ability to pay interest, the limitless ability to control interest rates paid by Treasuries, and the infinite ability to pay for anything, anytime, that sounds like the fiscal house is in good order. Because the debt-GDP ratio is meaningless, the following paragraphs are purely for entertainment purposes and should not be taken seriously. I have bolded the more humorous parts:Herbert Stein, head of the Council of Economic Advisers in the 1970s, observed that “if something cannot go on forever, it will stop.” If the U.S. doesn’t get its fiscal house in order, a future U.S. president will confirm the truth of that maxim. And if confidence in the world’s safest asset evaporates, everyone will suffer the consequences.

Jamie, Phil, and Viktoria have invented two definitions of “sustainability.” One is debt/GDP increases, which have been going on for over 80 years and have caused nothing. The other is interest expense, which the government has the endless ability to pay, is controlled by the Fed, and adds to GDP growth. Apparently, Jamie, Phil, and Viktoria don’t know we’ve passed those road signs, but we are still sustaining. Folks, you have been fed a steady, 80+ years diet of garbage, the purpose being to convince you the government can’t afford to give you benefits. The rich know better, so they get all the tax benefits. The media are bribed to feed you garbage by advertising dollars and ownership. The economists are bribed via contributions to schools and promises of lucrative employment in think tanks. The politicians are bribed by campaign contributions and employment after they leave office. Sadly, the public eats the garbage, so the people struggle while the rich laugh. Ignorance is costly. Rodger Malcolm Mitchell Monetary Sovereignty Twitter: @rodgermitchell Search #monetarysovereignty Facebook: Rodger Malcolm MitchellMethodology Bloomberg Economics uses the latest long-term CBO projections’ baseline fiscal and economic outlook—including the effective interest rate, primary budget balance as a percent of GDP, inflation as measured by the GDP deflator, and real GDP growth rate—as a starting point for the analysis. To calculate the debt-to-GDP ratio using market forecasts for rates, we substitute forward rates as of March 25, 2024, and project future effective rates on federal debt based on a detailed bond-by-bond analysis. To forecast the distribution of probabilities around the CBO’s baseline debt-to-GDP view, we conduct a stochastic debt-sustainability analysis: —We estimate a VAR model of short- and long-term interest rates, primary balance-to-GDP ratio, real GDP growth rate, and GDP deflator growth using annual data from 1990 to 2023. The covariance matrix of the estimated residuals is then used to draw one million sequences of shocks. —We use data on the maturities of individual bonds to map short- and long-term interest-rate shocks to the effective interest rate paid on U.S. federal debt. —Using this model, Bloomberg Economics considers two definitions of sustainability. First, we check if the debt-to-GDP ratio increases from 2024 to 2034. Second, we examine if the average inflation-adjusted interest expense, scaled by nominal GDP, over the ten years from 2025-2034 is less than 2%.——— (With assistance from Jamie Rush, Phil Kuntz, and Viktoria Dendrinou.)

……………………………………………………………………..

The Sole Purpose of Government Is to Improve and Protect the Lives of the People..

MONETARY SOVEREIGNTY