Once again, the so-called “debt ceiling” is in the news. The Republicans, who traditionally favor limiting federal spending, now support increasing it. The Democrats, who traditionally favor increased federal spending, now advocate for limiting it.

So, as of this writing, we are headed toward a stalemate, which threatens America’s economy.

The Basic Problem: Inflation

Money was created as a store of value and a medium of exchange. It is the basis of economics.

The earliest form of “standard money” appeared between 3000 and 2000 BCE in Mesopotamia, among the Sumerians and Babylonians. They utilized silver, measured by weight in shekels, as a standard of value for trade and record-keeping, even before the invention of coins. In Egypt, grain, metals, and other commodities served as units of account.

By around 2500 BCE, a form of money as a unit of account and medium of exchange was already in use.

Since then, nations have faced recessions, depressions, and stagflation; however, the primary concern in economics is inflation—the decrease in the value of a nation’s currency.

Money is an artificial construct of value. A dollar bill is simply printed paper, just like a check. Neither possesses intrinsic value, and both can be easily created. The concern is that creating too much money will lead to a reduction in its value.

To prevent inflation, governments try to limit their ability to create money.

Gold and silver are permanently available in physical form and somewhat scarce, so linking money to these elements (gold and silver standards) was a means of restricting the creation of money.

Gold Standard and the Debt Limit

The debt limit serves as a modern equivalent to the historical gold standard. While the two concepts have different impacts, both aim to limit the government’s ability to create money.

If not for the fear of inflation, neither a gold standard, a silver standard, nor a debt limit would have been invented.

Under a gold standard, each unit of currency (dollar, pound, franc, etc.) was pegged to a fixed weight of gold. The U.S. Gold Standard Act of 1900 set 1 troy ounce of gold to be equal to, $20.67. People could, in theory, redeem paper money for gold at that fixed rate.

The government couldn’t create new money freely; it had to maintain sufficient gold reserves to back it.

If a government runs large deficits and needs to spend heavily, it risks losing gold reserves because creditors or foreign nations might demand repayment in gold. Additionally, “breaking the peg” could trigger panic, bank runs, and a loss of confidence.

In practice, deficit spending was tightly constrained by gold holdings. Countries often had to raise interest rates, cut spending, or deflate their economies to protect reserves.

Gold standards and other physical currency pegs limit economic growth. This limitation is both their purpose and their shortcoming.

When the economy grows faster than the supply of gold, it leads to deflation, meaning there isn’t enough money relative to the amount of goods available. Moreover, if gold is depleted—such as when it’s sent overseas to cover trade deficits—countries are forced to reduce credit and spending, even during recessions.

This is why the gold standard worsened the Great Depression: the U.S. and Europe focused on defending gold reserves instead of stimulating their economies.

The U.S. suspended gold convertibility for domestic purposes in 1933.

Following World War II the Bretton Woods system was established, which pegged various currencies to the U.S. dollar. The dollar, in turn, was pegged to gold at a rate of $35 per ounce.

In 1971, President Nixon ended gold convertibility by “closing the gold window.” Since that time, the U.S. dollar has become fiat money, meaning it is not backed by any physical commodity but rather by U.S. law and the “full faith and credit” of the U.S. government.

The years spent dealing with the challenges of the gold and silver standards have ultimately been in vain. Today, inflation is no greater a problem since those standards have been abolished. Additionally, we have not experienced a depression since the end of the gold standard.

The debt ceiling is a legal limit set by Congress on the total amount of money that the U.S. Treasury can borrow to fulfill existing obligations.

The stated purpose is to control borrowing. It was originally intended (in 1917, with expansion in 1939) to give Congress oversight of federal borrowing while allowing the Treasury to issue debt without constant, individual approval.

Supporters claim it forces Congress to confront federal deficits and spending levels. Also, it allows legislators to make a public statement about debt, deficits, or fiscal responsibility.

In reality, the debt ceiling does not control new spending. Rather, it restricts the payment of existing obligations. Spending levels and taxes are set by Congress through separate budget and appropriations laws. Once those laws are passed, the Treasury is obligated to pay the bills.

The debt ceiling creates a risk of default. Once the ceiling is reached, the Treasury cannot issue new debt, even though it must meet legally required obligations such as Social Security, interest on the debt, Medicare, military pay, and contracts. This situation forces the use of “extraordinary measures,” and if it continues for too long, it could lead to a U.S. default.

Additionally, the debt ceiling has become a political tool. In recent decades, political parties have used debt ceiling votes to advance unrelated policy goals.

Most economists view the debt ceiling as economically unnecessary and politically hazardous. It does not actually limit future debt, as spending and tax laws determine that. Instead, it introduces an unnecessary risk of default that can destabilize markets and increase U.S. borrowing costs.

The United States is unique in having a separate debt limit; few other advanced economies impose such a restriction, as they allow borrowing to flow automatically based on budget decisions.

In summary, while the stated purpose of the debt ceiling is to promote fiscal restraint, its actual effect is often a result of political posturing that can have serious economic consequences.

Major Debt Ceiling Crises

Congress raised the debt ceiling several times during President Eisenhower’s presidency.

Even then, this effort has been more about political strategy than actual debt control. While Republicans have aimed to project a fiscally more conservative image, the ceiling continued to rise under both parties.

1979 – “Technical Default”: A clerical error, plus temporary cash-flow issues, caused a brief delay in paying Treasury bills. Investors demanded higher yields afterward—showing even the hint of default costs taxpayers.

1995–96 – Clinton vs. Gingrich: The Republican House, led by Speaker Newt Gingrich, refused to raise the ceiling without big spending cuts. Result: Two government shutdowns. The ceiling was eventually raised with no major long-term cuts.

2011 – Obama vs. House Republicans: The Republicans refused to raise the ceiling unless Obama agreed to major deficit reduction. Outcome: The U.S. came within days of default. The “Budget Control Act” imposed automatic spending caps (sequestration).

S&P downgraded the U.S. credit rating for the first time in history due to political dysfunction. As a result, stock markets fell and borrowing costs rose.

2013 – Obama Again: Another showdown over Obamacare and spending. The Treasury used “extraordinary measures” for months. The ceiling finally was suspended—but markets were rattled, with short-term Treasury yields spiking.

2013 – Obama Again: Another confrontation over Obamacare and spending. The Treasury employed “extraordinary measures” for several months. The ceiling was ultimately suspended, but markets were unsettled, causing short-term Treasury yields to spike.2013 –

2019 – Trump: A bipartisan deal suspended the debt ceiling for two years. Republicans largely dropped opposition to debt increases when they controlled the White House.

2021–2023 – Biden Era: Republicans initially refused to raise the ceiling; Mitch McConnell allowed a temporary extension at the last minute.

2023: With Republicans controlling the House, Speaker Kevin McCarthy negotiated a deal with Biden. The deal capped some discretionary spending growth for 2 years. Treasury had been within days of running out of money.

Notice the pattern? The stated purpose always is to “control debt and deficits,” but the actual outcome is that the debt ceiling always is raised or suspended (78 times since 1960), the so-called “debt” continues to rise, and the economy continues to grow.

Meanwhile, the side effects are market turmoil, higher borrowing costs, political theater, and in 2011, a credit downgrade.

Other advanced countries do not have this issue. In those countries, borrowing authority is automatically granted through the budget process.

The U.S. debt ceiling is unique because it creates artificial crises without altering fiscal reality.

Even the fundamental beliefs are wrong.

I. The Federal Government Does Not Borrow Dollars.

Federal finances are not like personal finances.

The federal government uniquely is Monetarily Sovereign. It has the unlimited ability to create dollars simply by pressing computer keys. It never unintentionally can run short of dollars.

Even if the federal government collected $0 taxes, it could continue spending trillions upon trillions of dollars, forever.

The notion that the government “borrows” comes from the semantic misunderstanding of the words “notes.” “bills,” and “bonds.” In the private sector, those words signify debt. But in the federal sector, they merely are forms of money, like “dollar bill” and “federal reserve note.”

II. Federal Deficit Spending Is Necessary for Economic Growth

Federal deficits inject growth capital into the economy. While the federal government has unlimited currency, the economy needs a steady inflow of dollars for expansion.

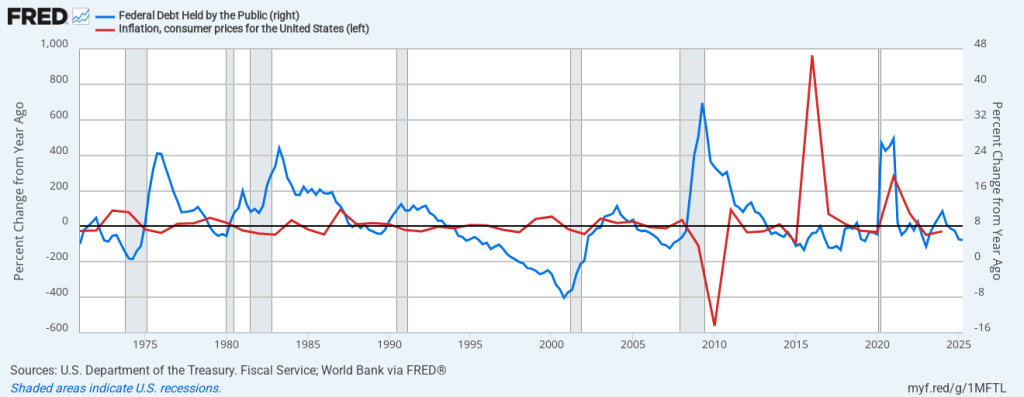

If federal deficits were economically harmful, one would not expect to see the graph above, which shows the economy’s growth paralleling the growth of deficits.

The reason is clear. GDP=Federal Spending + Nonfederal Spending + Net Exports.

III. Federal Deficit Spending Does Not Cause Inflation

“Following World War the Bretton Woods system was established…” > World War II

Whew! Longer than usual gap between RMM/MS posts. Happy to have you back.

LikeLike

Thanks, Steve

LikeLike

I last wrote about the unconstitutionality of the debt ceiling in 2023, one of 3 such articles, on opednews.com: https://www.opednews.com/populum/page.php?f=Updated-Debt-No-More-How-Banks_Constitution-In-Crisis_Constitution-The_Constitutional-Amendments-230526-519.html

The debt ceiling is unconstitutional not because Congress can’t set a limit on its own borrowing. It can enact any rule it wants to, no matter how silly. But it forces the president to pick and choose what to spend remaining funds upon, among expense ALREADY AUTHORIZED BY CONGRESS. That is the key thing, or at least it used to be until we got a president who thinks he can ignore the expressed will of congress and spend or not spend as he sees fit. The debt ceiling only encourages this misguided thinking, but unless SCOTUS or congress, including a few Republicans who recover their lost spines, insist the president “faithfully execute the law” including expenditures approved by congress, we won’t get constitutional spending.

LikeLike