Do You Keep A Diary?

I regret not having kept a diary. There is so much I have forgotten. Had I begun, say, at age 7, I could look back now and learn so much about myself.

Think about it. You find biographies interesting, but who really are you most interested in? YOU.

And yet, every year you age, memories disappear. A few may remain hidden but will be retrieved later. The vast majority are gone forever.

What a terrible loss. Your past is stripped away from you, never to be reclaimed. It’s as though you have a permanent case of Alzheimer’s, that every day, eats away at your brain.

Now, at 90, only the tiniest fraction of me remains, and I have no way to recover what’s lost.

I strongly recommend that every child be given a diary around the age of seven or eight. The child should be assured that no one will be allowed to read their diary, and they can hide it in a secret place of their choosing.

Siblings or others who violate this rule should understand they will face serious consequences.

Even before this age, parents might consider keeping a diary FOR the child to introduce the idea, and then give it to them as a precursor to their own diary.

Even if my parents had done so, I still would not have strong, independent memories of my life before five years of age — perhaps just vague shadows and hints — because infantile amnesia means my brain was restructuring, and certain kinds of memories are lost forever.

Memories that survive from early childhood often are fragmented, emotionally charged, or later reconstructed into false memories.

The causes are both neurobiological and cognitive: The hippocampus (key for episodic memory) is immature in the first few years of life.

Early memories may exist in implicit form (skills, habits, emotional responses) rather than explicit episodic form (narratives you can consciously recall).

The development of language around age 2–5 helps children encode memories in a way that can be recalled later.

I believe (can’t be certain) I remember from kindergarten (when I was five) being instructed to take my blanket from a cupboard, unroll it, lay it on the floor, and lying upon it, take a 20-minute nap.

I can visualize it, though it well may be a false visualization.

I also can visualize, at about the same age, looking down at my newborn sister lying in her crib, and marveling at her tiny fingers and toes. I remember mere curiosity rather than any emotional attachment to her as a sister. Rather, it was her as a little object that I shouldn’t break. Brotherly love would come later.

Around age five or so, the brain begins its shift from infantile implicit (tied to emotion, motor patterns, or routine memory networks) to more adult-like explicit memory networks.

So even a sad or reflective 7-year-old usually cannot reliably retrieve pre-5 memories; what he reports may be influenced by later knowledge, family stories, or imagination.

My regret at not having begun a diary is slightly offset by the suspicion that I might have lied.

Lying to one’s diary is actually more common than you may realize, and psychologists have studied it in different ways.

Self-image management: Individuals often seek to portray themselves favorably, even if only to themselves. Writing “I exercised today” when you didn’t, or “I handled that situation gracefully” when you didn’t, is a form of self-aggrandizing storytelling.

Memory reconstruction: Memory is malleable. When we recall events, we often unconsciously embellish, omit, or reinterpret them. A diary can be a mix of memory and aspiration.

Emotional regulation: Some people exaggerate or understate feelings to either feel better or to avoid confronting uncomfortable truths. Writing “I’m fine” when you aren’t can provide temporary emotional relief.

Studies of personal journals and diaries show that a significant number of entries contain self-deception or omissions, not only outright lies. Psychologists note that people often shape their narrative in ways that help them cope, not always strictly documenting facts.

The frequency may vary: For example, a lying-to-others survey shows a small proportion telling many lies and a large proportion telling none or few. By analogy, some diarists may rarely “bend the truth”, others may do so regularly.

A paper—“Diaries as Technologies for Sense making and Self transformation in Times of Vulnerability” —analysed long term online diaries (over 11–20 years) and described how diary writing serves for “sense making” and personal transformation, not just pure factual record keeping.

Imagine the freedom and honesty I might feel if I knew my diary was completely private. The slightest chance of its discovery, even postumous, would make me pause, but it’s such an intriguing thought.

Our legacy truly matters, even if we can’t witness its impact. This desire to connect and leave a mark speaks volumes

“We live in the minds of others without knowing it.” — Cooley’s “Looking Glass Self”

We constantly imagine how we will be remembered, even in contexts where we logically shouldn’t care. Though we won’t be around to feel the effects, we still care about our symbolic immortality and want our life to “add up” to something.

Psychologists call this legacy motivation, and it is universal across cultures.

A diary is private — but physical. It is written as if no one will read it, but preserved as if someone might. The mere existence of the object means it could outlive you — and therefore could judge you. Even dead, your story could embarrass you.

There’s an evolutionary and existential component:

We evolved in small groups where reputation influenced survival — even after death (your kin carried consequences). Many people hold implicit intuitions of the afterlife or unseen evaluation, even if explicitly non-religious. The future feels like a place where a version of “us” still exists — in others’ minds.

Much of human behavior is driven by a refusal to accept the finality of death. So yes — on some level, humans are not fully convinced that death is the end of their narrative.

Consider Donald Trump. He is elderly, seemingly unwell, eats poorly, and has a high-stress job. He easily could die within the year, if not the decade. Yet, he wants a Nobel Prize and a new stadium in Washington named after him.

Why? He may not live to enjoy these “prizes.” Not being overtly religious, he may even disbelieve in the afterlife. So what does he want? Momentary glory or something more?

We tell lies not just to avoid shame or to receive glory now, but also to avoid shame and to receive glory in a future we won’t even experience.

I’m 100% positive I will have no awareness after death. I’d bet my life on it. (Ha) But I can’t bear the thought of my children or grandchildren reading some of that stuff.

I’m not as good as my loved ones may believe, nor as bad as those who don’t like me believe. The problem is, I don’t care about the latter, but I deeply care about the former.

The potential audience affects truthfulness.

I really wish I had started a diary when I was young and continued it until now and beyond. I’d love to read about and remember the person I was as a grade-schooler, a teen, a college student, a husband, a father, a businessman, a retired man, and a grandfather.

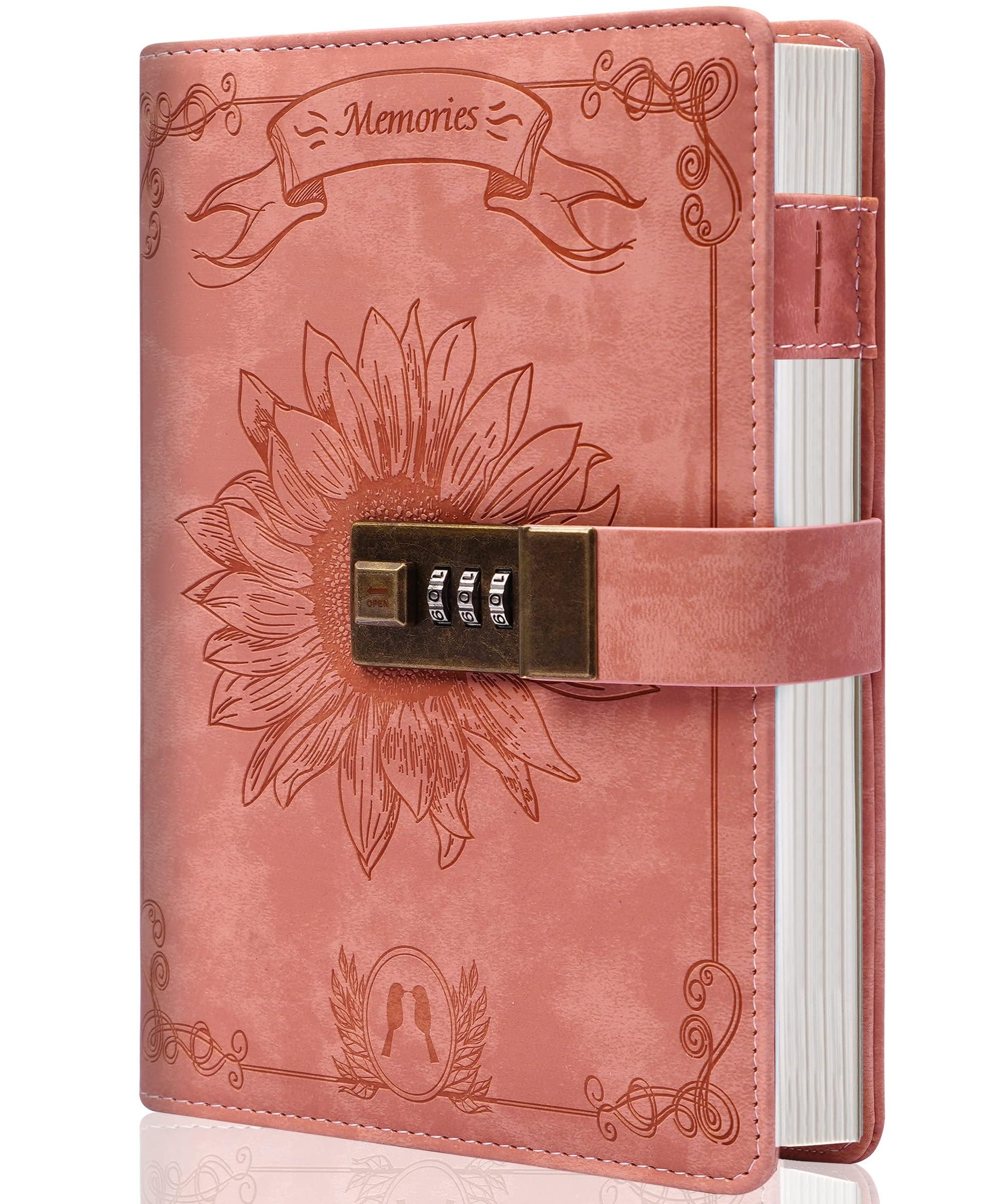

My advice: If you know any young people — even in their thirties or forties (young to me) — give them a diary, one with a combination lock, and encourage them to use it as honestly as they are able.

This holiday, I plan to give a diary to every young person in my family.

They will appreciate it, especially years later.

Rodger Malcolm Mitchell

Twitter: @rodgermitchell

Search #monetarysovereignty

Facebook: Rodger Malcolm Mitchell;

MUCK RACK: https://muckrack.com/rodger-malcolm-mitchell;

……………………………………………………………………..

A Government’s Sole Purpose is to Improve and Protect The People’s Lives.

MONETARY SOVEREIGNTY