Metaphysics has a bad reputation.

The mere mention of it brings forth images of wild-eyed psychopaths explaining with pseudo-scientific jargon, how alien species have been hovering over Area 51, causing COVID with a space ray while turning our children into insects.

The term “metaphysics” is generally interpreted to include topics that, due to their generality, lie beyond the realm of physics and its focus on empirical observation.

If something purported to be scientific yet “beyond the realm of physics,” it certainly is worthy of doubt. Yet, it is a prime source for creative thinking that yields accepted scientific findings.

Here are excerpts from an article in a respected scientific magazine, New Science.

How metaphysics probes hidden assumptions to make sense of reality All of us hold metaphysical beliefs, whether we realise it or not. Learning to question them is spurring progress on some of the hardest questions in physicsBy Daniel Cossins, 23 June 2025

“A lot of people think it’s a complete waste of time,” says philosopher Stephen Mumford at the University of Durham, UK, author of Metaphysics: A very short introduction. “They think it’s all just arguing over pointless questions, like, classically, how many angels could dance on the head of a pin?”

It isn’t difficult to see why. Classical metaphysics – the term comes from the Greek “meta”, meaning beyond – does ponder some bizarre-sounding questions. What is a table, for instance? What form of existence do colours have?

In addition, it does so through reasoning alone, with tools such as “reductio ad absurdum” – a mode of argumentation that seeks to prove a claim by deriving an absurdity from its denial. It is a far cry from the empirical knowledge scientists pursue through observation and experiment.

But the idea that metaphysics is all just abstract theorising with no basis in reality is a misconception, says Mumford: “Metaphysics is about the fundamental structure of reality beyond the appearances. It’s about that part of reality that can’t be known empirically.”

Indeed, as modern science has expanded its reach into territories that were once seen as the purview of metaphysics, such as the nature of consciousness or the meaning of quantum mechanics, it has become increasingly clear that one can’t succeed without the other.

“In many cases, metaphysical beliefs are the fundamental bedrock upon which empirical knowledge is built,” says Mumford.

Take causation – the idea that effects have causes – which we all believe despite the fact that causal connections aren’t observable. “Basically, the whole of science is premised on this metaphysical notion of causation,” he says.

These days, scientists routinely grapple with all manner of other concepts that are deeply infused with the metaphysical. From chemical elements, space and time to the concept of species and the laws of nature themselves – plus loads more.From the many worlds interpretation to panpsychism, theories of reality often sound absurd. Here’s how you can figure out which ones to take seriously

We have a choice, says Mumford. We can either scrutinise our metaphysical beliefs for their coherence or ignore them. “But in the latter case, we’re just assuming them unreflectively,” he says.

One of the most striking cases in which science and metaphysics collide is quantum mechanics, which describes the world of atoms and particles. It is a hugely successful scientific theory, yet when grappling with its meaning, physicists must confront metaphysical questions, like how we should interpret quantum superpositions, the apparent ability of a quantum system to exist in multiple states simultaneously.

Here, all we have are competing interpretations of what is actually going on that won’t submit to experimental testing, and it is becoming clear that progress will be impossible without confronting our hidden assumptions.

“In the end, you can’t do physics without metaphysics,” says Eric Cavalcanti at Griffith University in Brisbane, Australia.

In light of my previous metaphysical explorations concerning concepts like “free will,” “consciousness,” “space,” “dark energy,” and “time,” I humbly present to you “Everything: Gravity, Change, and the Glass Hammer.”

The “glass hammer” is my analogy for something unthinkable yet transparent — something that one might dismiss on first thought, and then think, “Wait a second. What if . . . “

Have you ever wondered, “What is everything made of?

You know that things are made of molecules, which are made of atoms. Atoms consist of electrons, neutrons, and protons, with protons being made of quarks. You feel confident in all that. But what is the fundamental substance of all these components?

Even more basic particles? Pure energy? Strings? Rings? Information? They all have been suggested by physicists, philosophers, and dreamers.

The peculiarities of quantum mechanics, which assert that a single object can exist in multiple locations at the same time, communicate faster than the speed of light, and that merely knowing something can influence that very thing, raise intriguing questions. These counterintuitive claims seem to pave the way for even more surprising concepts.

So here is one.

Perhaps the more interesting question isn’t about what everything is made of, but rather what influences everything. In other words, what is the universal cause behind every effect that exists everywhere? Is there one. A myriad?

I can visualize two concepts that seem to meet the test of universal cause: Gravity and Change. They are everywhere and they affect everything.

GRAVITY

Gravity seems to act like a force, but it isn’t a force. It’s the structure of space itself. Gravity creates space paths that tell mass where to move. Even in the absence of mass still exists. That curve—that geometry—is the substrate of everything else.

No particle escapes gravity. No field ignores it. No galaxy forms without it. No clock ticks unless space has shape. No place in the universe is devoid of gravity. It may not only be what things are made of so much as what gives things the property of existence.

CHANGE

Change also is what everything experiences. Just as gravity is everything, change is everywhere.

Nothing comes into existence without change. A thought is a change in the brain. Time is change ordered into sequence. Causality is change linked with explanation. Consciousness is the process of change, sensed. Quantum entanglement is a change expressed through correlation.

Change isn’t a side effect. It’s the “engine” of existence. Without change, there’s no becoming, no interaction, no perception, no event.

Without change, gravity is just fixed geometry. Without gravity, change is an empty promise.

But can change exist as a separate entity? It seems counterintuitive. If the universe were completely empty, could there be change?

THE FOUNDATION BENEATH THE FOUNDATION

Here’s a possibility: The Gravity Field is the “universal structure.” The Change Field is the “universal animator,” Everything else—particles, thoughts, time—is how structure responds to activity and how activity shapes structure.

So when we ask, “What is everything made of?”, the answer cannot be a specific thing. It must be a principle, a relation, or a rule so fundamental that it precedes any other occurrence.

That’s why the search for the ultimate answer always becomes metaphysical—not because it’s mystical, but because it has to reach below the level where “physics” even begins.

GRAVITY IS EVERYTHING If your search for universality includes parsimony—building the most complexity from the fewest tools—this is a strong starting point: Gravity shapes the possible. Change generates the actual.

Everything else just rides the line following them.

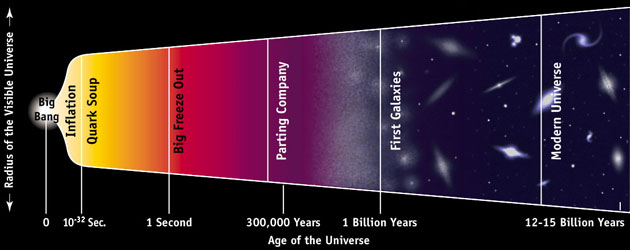

Visualize this: At or just before the singularity explosion you know as the “Big Bang—perhaps one Planck second before time as we know it—the first thing to exist was the change field.

Not matter, not energy, not even space, but the pure relational fact that something will not be the same from one moment to the next.

From this primordial flicker, the gravity field emerges as the first structure builder, the first geometry, the first form that gives shape to change.

Gravity doesn’t push or pull in the usual sense; it sculpts. It tells the changing “what” where to go. All else—particles, forces, time, space, and even consciousness—arise as complex echoes of that foundational field pairing: Change as cause, Gravity as form.

From the overlap of two fields, two metaphysical primitives merge, and the entire universe unfolds.

Can you see it? Before anything—before time, space, matter, or energy—there was only stillness. A frozen singularity, timeless and changeless, containing no structure, no motion, no direction.

Without the Change field, nothing happens. Without Gravity, nothing holds. Together, they animate the universe. Perhaps, like the graviton, there’s a hypothetical particle—a “chronon”—not just measuring Change, but enabling it. Without it, the cosmos remains a blank slate.

We come to the hard problem of imagining how Change could be a standalone. How could Change exist before there is any THING that can change?

But I see Change as not an inevitable part of existence. I can imagine that singularity, or whatever it was, existing for millennia without Change. I can visualize the possibility of an electron that never changes until something gives it “permission” or the “command” to change.

I can imagine change as a field that, when combined with the gravity field, initiates the evolution of the universe.

AN ANALOGY

We often picture the Big Bang as an explosion—a furious, fiery instant when the universe bursts into being. But what if it wasn’t an explosion at all? What if it was an intersection?

Not of matter, or even energy—but of two fundamental, pre-physical fields: one representing change, and the other, structure—what we now call gravity.

Imagine a universe before time. Not a moment before, but a condition without motion, without process—only potential.

In this frozen realm, two great fields exist. One, the Gravity Field, shaped but inert, a vast topology of possible forms. The other, the Change Field, is dynamic in nature but without a canvas to act upon.

Separately, neither produces reality. But at the instant they intersect, time begins. The coupling of change with structure triggers motion, energy, and evolution—a cosmos.

To visualize this, consider a simple metaphor: The moire pattern.

When the patterns exist separately, they do nothing. But move them even slightly, and the most astounding patterns suddenly emerge. Watch how the patterns change faster than the merger itself.

In fact, through time, the pattern moves faster and faster. Does that remind you of dark energy?

In a similar way, the intersection of the Change Field and Gravity Fields may have emerged across an entire volume of proto-space instantaneously. From within the universe, it would appear to expand faster than light—not because anything traveled superluminally, but because the rules of existence themselves had shifted.

It explains how the universe could expand faster than light, while containing light.

There was no “before” the intersection because time had not yet been written into the structure. The Big Bang was not a fireball—it was the first place geometry was set in motion.

What followed—particles, forces, even consciousness—may be the natural unfolding of that single event: the moment change met gravity and the universe became real.

Sometimes, metaphysics is necessary to explain what physics cannot. You may need to squint or rely on your peripheral vision to see it. (See: New Scientist Magazine: How metaphysics probes hidden assumptions to make sense of reality)

Metaphysical speculation is a good creative exercise as long as you don’t go too far down the rabbit hole. But, of course, this leaves open the question, “What is too far down?”

An object being in two places at the same time? You, changing an object simply by knowing it? Instant communication over a distance of light years?

Rodger Malcolm Mitchell

Twitter: @rodgermitchell

Search #monetarysovereignty

Facebook: Rodger Malcolm Mitchell;

MUCK RACK: https://muckrack.com/rodger-malcolm-mitchell;

……………………………………………………………………..

A Government’s Sole Purpose is to Improve and Protect The People’s Lives.

MONETARY SOVEREIGNTY

changing an object simply by knowing it?

What changes occur to the object? So, a ball of steel changes when I know its weight? My understanding changes, but the ball of steel is untouched.

LikeLike

You’re in good company. Einstein famously said, “I like to think the moon is there even if I am not looking at it.”

This statement captures Einstein’s realist discomfort with the Copenhagen interpretation of quantum mechanics, which suggests that unmeasured phenomena don’t have definite properties until they are observed. Einstein strongly rejected the idea that reality depends on observation, hence his famous objection: “God does not play dice with the universe.”

In contrast, Bohr and others argued that quantum properties are undefined until measured—a deeply probabilistic, non-deterministic view that Einstein disliked.

So while the moon quote may not have been formally published by Einstein, it accurately reflects his philosophical stance on objective reality existing independently of observation.

LikeLike

Objectivity and subjectivity can’t be separated. Everything must pass through human scrutiny. The general idea is to bring them as close as possible to agreement through experimentation, reality vs. what we think is reality.

LikeLike

August 8, 2025

13 min read

Physicists Can’t Agree on What Quantum Mechanics Says about Reality

https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/physicists-divided-on-what-quantum-mechanics-says-about-reality/?utm_source=Klaviyo&utm_medium=email&utm_campaign=TIS_080825&utm_term=what%20quantum%20mechanics%20says%20about%20reality&_kx=09ioRVvFs6cIBTEk3Yt-_6P9BcnLS3IYdcERGLooM0U.WEer5A

A survey of more than 1,000 physicists finds deep disagreements in what quantum theories mean in the real world

By Elizabeth Gibney & Nature magazine

Quantum mechanics is one of the most successful theories in science — and makes much of modern life possible. Technologies ranging from computer chips to medical-imaging machines rely on the application of equations, first sketched out a century ago, that describe the behaviour of objects at the microscopic scale.

But researchers still disagree widely on how best to describe the physical reality that lies behind the mathematics, as a Nature survey reveals.

At an event to mark the 100th anniversary of quantum mechanics last month, lauded specialists in quantum physics argued politely — but firmly — about the issue. “There is no quantum world,” said physicist Anton Zeilinger, at the University of Vienna, outlining his view that quantum states exist only in his head and that they describe information, rather than reality. “I disagree,” replied Alain Aspect, a physicist at the University of Paris-Saclay, who shared the 2022 Nobel prize with Zeilinger for work on quantum phenomena.

To gain a snapshot of how the wider community interprets quantum physics in its centenary year, Nature carried out the largest ever survey on the subject. We e-mailed more than 15,000 researchers whose recent papers involved quantum mechanics, and also invited attendees of the centenary meeting, held on the German island of Heligoland, to take the survey.

The responses — numbering more than 1,100, mainly from physicists — showed how widely researchers vary in their understanding of the most fundamental features of quantum experiments.

As did Aspect and Zeilinger, respondents differed radically on whether the wavefunction — the mathematical description of an object’s quantum state — represents something real (36%) or is simply a useful tool (47%) or something that describes subjective beliefs about experimental outcomes (8%). This suggests that there is a significant divide between researchers who hold ‘realist’ views, which project equations onto the real world, and those with ‘epistemic’ ones, which say that quantum physics is concerned only with information.

The community was also split on whether there is a boundary between the quantum and classical worlds (45% of respondents said yes, 45% no and 10% were not sure). Some baulked at the set-up of our questions, and more than 100 respondents gave their own interpretations (the survey, methodology and an anonymized version of the full data are available online).

“I find it remarkable that people who are very knowledgeable about quantum theory can be convinced of completely opposite views,” says Gemma De les Coves, a theoretical physicist at the Pompeu Fabra University in Barcelona, Spain.

Nature asked researchers what they thought was the best interpretation of quantum phenomena and interactions — that is, their favourite of the various attempts scientists have made to relate the mathematics of the theory to the real world. The largest chunk of responses, 36%, favoured the Copenhagen interpretation — a practical and often-taught approach. But the survey also showed that several, more radical, viewpoints have a healthy following.

Asked about their confidence in their answer, only 24% of respondents thought their favoured interpretation was correct; others considered it merely adequate or a useful tool in some circumstances. What’s more, some scientists who seemed to be in the same camp didn’t give the same answers to follow-up questions, suggesting inconsistent or disparate understandings of the interpretation they chose.

LikeLike