.

It takes only two things to keep people in chains:

The ignorance of the oppressed

and the treachery of their leaders.

——————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————–

In a May, 2010 talk at the University of Missouri, Kansas City, I said, “Because of the Euro, no euro nation can control its own money supply. The Euro is the worst economic idea since the recession-era, Smoot-Hawley Tariff. The economies of European nations are doomed by the euro.”

My reason was something that should have been obvious to anyone with even a smattering of knowledge about economics. Every euro nation was forced to surrender the single most valuable asset any nation can have: It’s Monetary Sovereignty.

A Monetarily Sovereign (MS) government has complete control over its own sovereign money. An MS government can control the supply and the value of its money. It can pay any debt denominated in its sovereign currency. It can create its sovereign currency at will, simply by paying bills.

An MS government never can run short of its sovereign currency, never can be “burdened” by debt, never can find debt “unsustainable,” and never needs to ask anyone (taxpayers or lenders) for infusions of its sovereign currency.

The U.S. government, for instance, has absolute power over the dollar, which gives lie to all the debt “Henny Penny’s” who for at least 77 years, have claimed the federal deficit and debt are in some vague way a threat to the government or to American taxpayers.

So it was with guilty but pleasurable feelings of “I told you so,” that once again I publish excerpts from an article that appeared in the “Naked Capitalism blog:

Why Does the Euro Area Have Such Low Growth and High Unemployment?

Posted on November 11, 2017 by Yves Smith

By Philip Arestis, Professor of Economics at the University of the Basque Country, Spain and Malcolm Sawyer, Professor of Economics, University of Leeds. Originally published at Triple CrisisSince the euro was adopted as a virtual currency in 1999 (and the exchange rates between the currencies of the then 11 countries fixed en route to adopting the euro), growth among the euro-area countries has been lacklustre.

The euro-area annual growth rate was just under 2% in 2002 to 2007, followed by 0.3% in 2008, -4.5% in 2009, then 2% in 2010, and an average of 0.8% 2011 to 2016. Over the period 1999 to 2016, the average was 1.1%.

Unemployment declined through to 2007 down to 7.5%, then rose in the aftermath of the financial crises and the effects of fiscal austerity programmes to 12% in 2013, and has gently declined since to 10% in 2016 and likely to come close to 9% at the end of October 2017.

There are notable disparities between different countries’ experiences, with Italy’s growth 1998 to 2016 being an annual average rate of 0.2%, and unemployment in Greece over 23% and Spain close to 20% in 2016.

We pause to examine the term, “fiscal austerity,” which I bolded for your convenience. It is a term that describes a government’s efforts to limit or reduce its deficits and debt.

Fiscal austerity is inevitable, even mandatory, for all monetary non-sovereign nations.

In America, city, county, and state governments, all being monetarily non-sovereign, continually must practice fiscal austerity, lest they eventually be unable to pay their bills.

No monetarily non-sovereign government can survive long-term on taxes alone. All monetarily non-sovereign governments require money coming in from outside their borders.

U.S. cities survive by borrowing, by trade surpluses, and by receiving dollars from county and state governments. County and state governments survive the same way, and additionally by receiving dollars from the federal government, which the federal government provides by running deficits vs. the states.

The Monetarily Sovereign federal government can survive forever, even while running deficits, and even while collecting $0 in taxes.

The euro nations are much like U.S. cities, counties, and states, all of which require euros coming in from outside their borders, just to survive, let alone to grow economically.

But from where will these additional euros come? They can come from borrowing (which is limited by the need to repay), net exports (though not all nations can be net exporters), or from the European Union (which requires that the EU itself run deficits).

Gross Domestic Product = Government Spending + Non-government Spending + Net Exports

Increasing any of the three factors — government spending, non-government spending, or net exports — requires an increased supply of money. This formula tells you a growing economy requires a growing supply of money.

Mathematically, it is impossible for an economy to grow while its money supply shrinks.

This all boils down to one absolute truth: The long-term survival of monetarily non-sovereign governments requires input from one or more Monetarily Sovereign governments, which in turn, requires the MS governments to run deficits.

The launch of the single currency had a whole range of political forces behind it, but was viewed as enhancing economic integration and giving some boost to trade between member countries.

“Boosting trade” always was the public excuse to the euro. But trade does not grow the overall money supply; it only transfers money from one nation to another.

Because a growing money supply is necessary for a growing economy, intra-EU trade does not grow the overall EU economy.

Many of the “structural reforms” have detrimental effects on inequality and productivity. “Reforms” attacking the level of minimum wages and undermining the position of trade unions exacerbate inequality.

“Reforms” attacking employment protection and security of employment do not help to foster training and innovation. Indeed, “structural reforms” were promoted to reduce “structural unemployment” and yet it is notable that the rate of “structural unemployment” in 2016 was 8.9%, compared with an average of 9.0% in the period 1992-2001, and 9.1% over 2002=2011.

Those favoring austerity always title their actions “Reforms.” Thus today, in America, we have “tax reform,” the ostensible purpose of which is to reduce (beneficial) deficits and debt, but which really is designed to increase the Gap between the rich and the rest.

The operations of the euro area (and the Economic and Monetary Union) are hampered by restrictive fiscal policies which strive for balanced budgets.

The attempt at a uniformity of fiscal policy (with the common aim of a “balanced structural budget”) cannot take into account the differing needs of countries for infrastructure investments nor does it take into account the differing economic circumstances of countries.

Balanced budgets also do not take into account the fact that government deficits add money to the private sector. When any government entity, whether Monetarily Sovereign or monetarily non-sovereign, runs a surplus, the private sector it serves runs a deficit — which is recessive.

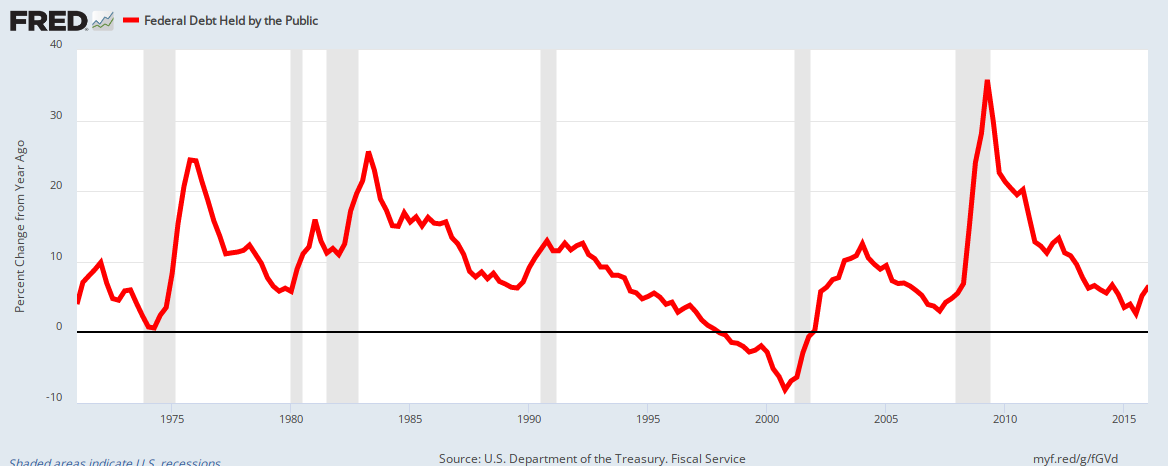

In America,for instance, economic growth has required not just deficits, but deficit growth. Reductions in deficit growth have led to recessions, while increased deficit growth has cured recessions.

The adoption of the euro took place without any thought to the current-account imbalances between the member countries, and without any perspective on the sustainability of those imbalances.

Translation: Some euro nations had net exports of goods and services (i.e. imports of euros) and so, prospered. The others had net imports of goods and services (exports of euros), so suffered.

The current-account imbalances grew in the first decade of the euro, with associated capital flows between countries. In the second decade of the euro, current-account deficits were drastically reduced as internal deflation brought imports down.

But the underlying pattern of imbalances has not been resolved, and countries with high unemployment seeking a return to prosperity will face severe constraints from their current-account position.

Translation: The net-import, monetarily non-sovereign nations have no way to stimulate their economies by growing their money supply.

The austerity policy agenda (from the Stability and Growth Pact, the “fiscal compact,” etc., with the drives for balanced budgets), the pursuit of “structural reforms,” and the failures to address the current account constraints on euro-area member countries have all contributed to the lacklustre economic performance.

In Summary:

Austerity (i.e. the reduction of deficits and debt), reduces the growth of a nation’s money supply, which in turn, reduces economic growth, and even leads to recessions and depressions.

1804-1812: U. S. Federal Debt reduced 48%. Depression began 1807.

1817-1821: U. S. Federal Debt reduced 29%. Depression began 1819.

1823-1836: U. S. Federal Debt reduced 99%. Depression began 1837.

1852-1857: U. S. Federal Debt reduced 59%. Depression began 1857.

1867-1873: U. S. Federal Debt reduced 27%. Depression began 1873.

1880-1893: U. S. Federal Debt reduced 57%. Depression began 1893.

1920-1930: U. S. Federal Debt reduced 36%. Depression began 1929.

1997-2001: U. S. Federal Debt reduced 15%. Recession began 2001.

Monetarily non-sovereign governments are forced into austerity by their inability to create the money they use.

Monetarily Sovereign nations have the unlimited ability to create their own sovereign currency, but may intentionally be taken into austerity by government malfeasance on behalf of the rich.

Keep this in mind as Congress and the President debate tax “reform,” health care “reform,” and other so-called fiscal “reforms,” that are designed to widen the Gap between the very rich and you.

Deficit reduction guarantees economic death.

Rodger Malcolm Mitchell

Monetary Sovereignty

Twitter: @rodgermitchell; Search #monetarysovereignty

Facebook: Rodger Malcolm Mitchell

………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………..

THE WAY THINGS ARE:

•All we have are partial solutions; the best we can do is try.

•Those, who do not understand the differences between Monetary Sovereignty and monetary non-sovereignty, do not understand economics.

•Any monetarily NON-sovereign government — be it city, county, state or nation — that runs an ongoing trade deficit, eventually will run out of money no matter how much it taxes its citizens.

•The more federal budgets are cut and taxes increased, the weaker an economy becomes..

•No nation can tax itself into prosperity, nor grow without money growth.

•Cutting federal deficits to grow the economy is like applying leeches to cure anemia.

•A growing economy requires a growing supply of money (GDP = Federal Spending + Non-federal Spending + Net Exports)

•Deficit spending grows the supply of money

•The limit to federal deficit spending is an inflation that cannot be cured with interest rate control. The limit to non-federal deficit spending is the ability to borrow.

•Until the 99% understand the need for federal deficits, the upper 1% will rule.

•Progressives think the purpose of government is to protect the poor and powerless from the rich and powerful. Conservatives think the purpose of government is to protect the rich and powerful from the poor and powerless.

•The single most important problem in economics is the Gap between the rich and the rest.

•Austerity is the government’s method for widening the Gap between the rich and the rest.

•Everything in economics devolves to motive, and the motive is the Gap between the rich and the rest..

MONETARY SOVEREIGNTY

It has occurred to me your graph above of the recessions/depressions since 1804, has a big problem. It cannot be the US federal debt reduction that causes them. As you write, the Federal Debt is the investor savings accounts held in the Fed. So how do we say its budget surplusses that lead to recession? Federal debt reduction is like a tax cut. It adds to non government savings. Or am I missing something?

LikeLike

Excellent comment.

Indeed, the deficit and the debt are two different things — but not unrelated things.

By law, the federal government must sell T-securities (i.e. accept deposits in T-security accounts) to equal the net total of deficits. So from a legal standpoint, and not because of any fiscal connection, deficits “cause” debt.

If the total debt increases from one year to the next, the amount of that increase must equal the “deficit.” If the debt decreases, the amount of decrease equals the “surplus. Thus, a graph showing year-to-year changes in debt actually demonstrates deficits (or surpluses).

You are correct that changes in debt do not lead to recessions, but changes in debt reflect changes in deficits, which do lead to recessions.

Federal debt reduction is nothing like a tax cut. A tax cut increases the money supply. Reducing the debt requires reducing the deficit, which would reduce the money supply.

I’m not sure whether I’ve made this clear. If you have further questions, don’t hesitate to express them.

LikeLike

Thanks. I understand the deficit and surplus figures are annual ones, reset each year. They can’t increase from year to year, save in the accounting records. The government has/doesn’t have any money of its own. So government debt is just deposits from investors. I see no link between them, unless the bond sales failed to match the deficit, which I haven’t heard of? [Not all nations have that requirement of selling bonds to match deficits, although the EU does for Britain].

So it’s just smoke and mirrors all due to the misunderstanding of what government debt is?

LikeLike

Yes, that one misunderstanding is the root of all ignorance about federal financing.

LikeLike

OK, that’s what I was wanting to clear up. Still, using Gov debt as a yardstick just continues the problem.

LikeLike

PS have you seen John T Harvey’s piece in Forbes on “Trump’s disastrous tax plan” well worth reading; https://www.forbes.com/sites/johntharvey/2017/11/08/disastrous-trump-tax-plan/#21b680484dd3

LikeLike