Mitchell’s laws: The more budgets are cut and taxes inceased, the weaker an economy becomes. To survive long term, a monetarily non-sovereign government must have a positive balance of payments. Austerity = poverty and leads to civil disorder. Those, who do not understand the differences between Monetary Sovereignty and monetary non-sovereignty, do not understand economics.

==========================================================================================================================================

Debt hawks have a predictable argument. First they say the deficit and debt are “unsustainable” (a favorite word). When you challenge them to define “unsustainable,” they say the federal government will not be able to continue servicing a growing debt “forever’ (another favorite word).

When you tell them a Monetarily Sovereign nation has the unlimited ability to create its sovereign currency, so can service any debt of any size, they switch positions. They then claim that money “printing” (yet another favorite word) causes inflation. Finally, they mention Weimar Republic and Zimbabwe, two nations whose hyper-inflation caused money creation and not the other way around.

Let’s ignore the fact that the federal government does not “print” money. It creates dollars by the act of paying its bills. The Treasury does print dollar bills, but they aren’t money; they are evidence of dollar ownership.

Instead, let’s get to the point, which can be summarized in three questions:

1. Will federal dollar creation cause inflation?

2. Are low interest rates stimulative?

3. Is inflation a greater threat than recession?

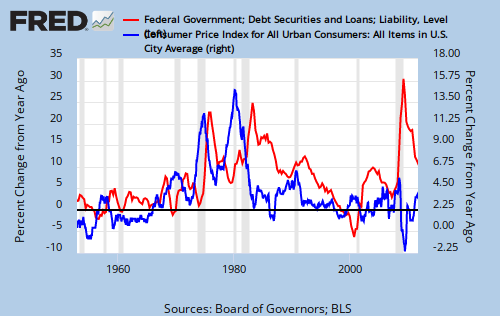

The first question can be addressed by the following graph.

The red line shows the federal deficit; the blue line shows the Consumer Price Index. As you can see, for at least the past sixty years (!) there has been zero relationship between federal deficit spending and inflation. This is discussed in greater detail at: Oil causes inflation.

As for whether inflation is a greater threat than recession, we already are in, and have been in, a recession. Millions of people are suffering from joblessness and poverty. By contrast, inflation remains about what the Fed wants it to be: 2% – 3%. So you tell me which is the greater threat.

I mention this because of an article that appeared in today’s Washington Post. Here are some excerpts:

Fed Inflation Hawks Warn More Stimulus Could Fuel Prices

By Sam GustinAre inflation hawks preparing to take flight? That’s the sense one gets reading comments made by two U.S. central bank officials Tuesday, including Dallas Fed President Richard Fisher, who said that corporate chiefs have been sounding the alarm about an increase in prices thanks to the Fed’s easy money policy.

Fisher’s latest remarks are sure to fuel a growing debate about whether the Fed should embark on another round of monetary stimulus, especially in light of last month’s lackluster jobs report.

Fisher said that he’s heard from business leaders who are concerned that the Fed’s easy money policy could raise inflation, which would increase prices for companies just as they’re trying gain a solid footing.

“I’m just reporting what I hear on the street, which is a real concern that with our expanded balance sheet, we are just a little bit in an ember of what could become an inflationary fire,” Fisher said in comments cited by Bloomberg.

He said business leaders are telling him, “Please, no more liquidity.”

This is economics? What he’s heard on the street? And are business leaders really begging for no more stimulus? Gimme a break. It’s total BS.

Separately, Minneapolis Federal Reserve Bank President Narayana Kocherlakota said that the threat of inflation means that the central bank will likely have to begin to reverse its easy money policy as early as the end of the year.

“Conditions will warrant raising rates some time in 2013 or, possibly, late 2012,” Kocherlakota said in comments cited by Reuters.

That puts Kocherlakota at odds with the policy-making Federal Open Market Committee, which has said since January that it plans to keep interest rates low through 2014.

Confused nonsense. Low interest rates are not stimulative. (See: The low interest rate/GDP fallacy)

In fact, the opposite is true. Low rates hinder economic growth. Ask anyone holding CD’s, bonds or Treasuries.

So yes, by all means, raise interest rates.

Fisher and Kocherlakota are well-known inflation hawks, which means they tend to worry more than other policy-makers about the risk that inflation poses to the economy.

So it’s not surprising that Fisher, in particular, would voice business leaders’ concerns that inflation could make buying the materials — or inputs — they need to run their companies more expensive.

And that answers it. These guys mistakenly fear inflation more than recession (Think of what affects them personally, with their guaranteed, recession-proof salaries.)

And they mistakenly believe federal spending is the cause of inflation. And they mistakenly believe low interest rates are stimulative. And they mistakenly base policy on what someone says on the street.

Considering these are “experts,” is it any wonder the public is confused?

Fisher is the more hawkish of the pair. He’s called the idea of more monetary stimulus a “fantasy of Wall Street,” while Kocherlakota has allowed that “if the outlook for inflation fell sufficiently and/or the outlook for unemployment rose sufficiently, then I would recommend adding accommodation.”

Here’s where the real confusion emerges. Yes, monetary policy, (usually focused on interest rates), is a fantasy for economic growth, although interest rates do control inflation.

But fiscal policy (usually focused on deficit spending), is reality. Deficits are stimulative and the lack of deficits is recessionary and deflationary.

Bottom line:

1. Low interest rates are not stimulative; high rates are stimulative.

2. High rates fight inflation.

3. Federal deficit spending has not caused inflation for 60 years, though deficit spending is stimulative.

So to grow the economy without inflation, raise interest rates and increase deficit spending. And by all means, don’t listen to debt-hawks. They hate the word “debt,” without knowing why; they don’t understand Monetary Sovereignty; and they ignore economic reality.

Rodger Malcolm Mitchell

http://www.rodgermitchell.com

![]()

==========================================================================================================================================

No nation can tax itself into prosperity, nor grow without money growth. Monetary Sovereignty: Cutting federal deficits to grow the economy is like applying leeches to cure anemia. Two key equations in economics:

Federal Deficits – Net Imports = Net Private Savings

Gross Domestic Product = Federal Spending + Private Investment and Consumption + Net exports

#MONETARY SOVEREIGNTY

In a perfect world, the Fed’s inflation target would be one percent, which would force them to keep interest rates high.

Incidentally, Japan has raised its inflation target. This exemplifies why America still has the world’s largest economy: our strongest economic competitors have even more wrongheaded policies than us.

LikeLike

Tyler, you bring up an interesting point. Where did 2%-3% come from? My speculation is they want to be sure there is some inflation, and since inflation control is not precise, they want to be sure they don’t dip to 0% or lower.

If they had perfect control, they might well make 1% the target.

Rodger Malcolm Mitchell

LikeLike

Perhaps, a chart is worth a million words.

The red line shows the federal deficit; the blue line shows the Consumer Price Index.

What an interesting chart !

N.B. At the beginning of the shaded area denoting a recession (the red line) the federal deficit starts to increase and then

peaks at the end.

Could this mean,” increase in the federal deficit eventually brings an end to recession”?

N.B. Prior to any recession (the blue line) the consumer index is increasing in its relationship over the federal deficit.

Could this mean ,”increase in the Consumer Price Index with an increase in the gap between the CPI and the federal deficit

may cause a recession?

LikeLike

Carmen, regarding your first question, I called attention to this in the very first post on this blog. It’s at https://rodgermmitchell.wordpress.com/2009/09/07/introduction/

Look at item #4. Recessions are preceded by periods of declining deficit growth, and cured with increases in deficit growth. That is a fundamental tenet of Monetary Sovereignty. (By the way, depressions are preceded by periods of federal surpluses, which also is shown in that first post.)

You also are correct that inflations seem to introduce recessions. When the cost of goods and services rises and the availability of dollars rises more slowly, people can buy less, which leads to recession.

LikeLike

RMM,

I think there is an issue that you ignore. Sure, during a balance sheet recession low interest rates are not stimulative because there are not enough credit worthy borrowers AND there is not enough aggregate consumer demand for the low interest rates to have an effect.

But, during “boom” (or bubble?) times… wouldn’t low rates be stimulative? It seems there would be plenty of credity worth borrowers and aggregate consumer demand that, when couple with low interest rates, those low interest rates would indeed be more stimulative than higher interet rates? Do you disagree?

If you agree, then it’s not really fair to say that low interest rates are not stimulative because it depends on the current economic environment. i.e. during a recession they may not be, but during a procession they would be (can the word “procession” be used here?)

LikeLike

JK,

The actual facts dispute the theory.

If you look at the post I referenced above (“The low interest rate/GDP fallacy”) you’ll see that in fact, low rates are not associated with high GDP growth. Quite the opposite.

I suspect the reason is that low rates require the federal government to pay less interest, thereby pumping fewer dollars into the economy.

Rodger Malcolm Mitchell

LikeLike

RMM : “I suspect the reason is that low rates require the federal government to pay less interest, thereby pumping fewer dollars into the economy.””

Surely, a Monetary Sovereignty could circulate all the currency that it wishes without paying any interest at all.

So,as Ellen Brown says,Why do we continue that stupid practice of paying interest on our own money?

LikeLike

Right. The stupid practice is issuing T-securities, which no longer have a purpose.

LikeLike

It seems like you’re arguing that a correlation is a causation…

For example, could it be that low interest rates are “associated” with lower GDP growth precisely because the Fed lowers interest rates when GDP is sluggish. Likewise, the Fed increases interest rates when the GDP is booming and they are worried about inflation. Meaning, yes.. there is a positive correlation between the two, but the question remains: which would causes the other one to move in the same direction?

If a lowering of interest rates is followed by decreased GDP growth, then your claim seems right on. But if a lowering of interest rates follows sluggish GDP growth, then it seems your argument doesn’t make sense.

I read the link that you posted (The low interest rate/GDP fallacy) and it appears that the red line, GDP growth, typically dips first.. and the blue line, the federal funds rate, follows with a positive correlation: when GDP falls, then the FFR begins to fall; and when GDP rises, then the FFR begins to rise.

Doesn’t that suggest the opposite of what you’re saying is true?

LikeLike

Sorry,,, the one paragraph should read:

If a decreasing FFR is followed by GDP decreasing, then your claim seems right. But if a decreasing GDP is followed by the FFR decreasing, then it seems yoru argument doesn’t make sense”

Again, it seems like the FFR “follows” GDP. Wouldn’t that suggest the opposite of what you’re saying?

LikeLike

JK,

Yes, the Fed tries to anticipate inflation by raising rates. The Fed also tries to stimulate the economy by lowering rates. The problem: Inflation doesn’t necessarily correlate with GDP growth: http://research.stlouisfed.org/fredgraph.png?g=6p6

So the Fed uses one tool to deal with two separate, often unrelated problems.

You are correct that coincidence is neither cause nor correlation. One of the difficulties has to do with timing, i.e., how long it takes for a cause to have an effect.

LikeLike

Even more importantly. “I choose to interpret the episode as illuminating a blind spot in traditional economic thinking.”

http://physics.ucsd.edu/do-the-math/2012/04/economist-meets-physicist/

“…we do not share the view of many of our economics colleagues that growth will solve the economic problem, that narrow self-interest is the only dependable human motive, that technology will always find a substitute for any depleted resource, that the market can efficiently allocate all types of goods, that free markets always lead to an equilibrium balancing supply and demand, or that the laws of thermodynamics are irrelevant to economics.”

LikeLike

Good article, worth reading.

The blind spot is the definition of “growth” and of “Product” (in GDP). Assuming we achieve a future, stable population (which I believe will occur), what will “economic growth” mean?

Economic growth will not require that each of us has more clothing, more food, more houses and more toys. There will be a transformation in how “growth” is defined, and I anticipate it will have to do with a satisfying lifestyle, not a “more” lifestyle.

Clothing, food, housing and toys will be better, however “better” is defined.

The clearly biased author of your recommended piece (Notice how it is the economist who is coughing and choking), has fallen into the classic futurist trap: Assuming everything, including definitions, will remain the same, then projecting from there.

I almost laughed out loud, when the author said, ” . . . today’s supercomputer eats 50,000 times as much as a person does, so there is a big gulf to cross.” He gave the solution to his own problem. The human brain is far more powerful than any supercomputer and uses far less energy. Who is to say tomorrow’s quantum computer can’t surpass that?

Bottom line: Based on today’s definitions of “growth” and “Product,” some wish us to create less and to consume less, i.e. adopt a more austere lifestyle. Aside from the psychological impossibility of holding all humankind to a style adopted by, for instance, the Amish, would that really solve the problem?

Would an entire world of Amish change the dire, energy/entropy predictions of the physicist? I think not.

The long term salvation of the world is not to surrender all that smacks of progress, and return to a tribal existence, but rather to use the brains we were given to create a sustainable progress.

Rodger Malcolm Mitchell

LikeLike

Sheila Bair sees inflation as the greater threat: http://www.washingtonpost.com/opinions/fix-income-inequality-with-10-million-loans-for-everyone/2012/04/13/gIQATUQAFT_print.html

LikeLike