Those, who do not understand the differences between Monetary Sovereignty and monetary non-sovereignty, do not understand economics.

================================================================================================================================================================================================================

Thirteen months ago, I published a post titled, “Is federal money better than other money.” I believed it was one of the more interesting posts in this long series, because it showed that while reduced federal debt growth led to recessions, increased non-federal debt growth also led to recessions.

At the time, the data stopped at February, 2002. I now have brought the data forward, and am republishing. These new data support the previous findings.

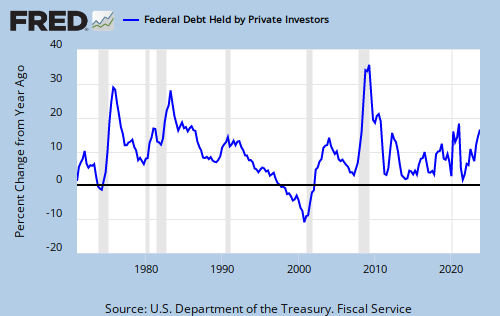

In other posts on this blog, we have discussed how reductions in federal debt growth, as shown by the following graph, “Federal Debt Held By Private Investors,” immediately precede recessions. This comes as no surprise, since a growing economy requires a growing supply of money, and deficit spending is the federal government’s method for adding money to the economy.

Clearly, federal debt/money growth is essential to keep us out of recessions. Yet, when we look at “Debt Outstanding Domestic Nonfinancial Sectors” which includes not only Federal debt, but also outstanding credit market debt of state and local governments, and private nonfinancial sectors (tan line), we do not see the same pattern.

In fact, when we subtract federal debt from total debt, leaving only state, local and private debt, we see the opposite pattern. Recessions follow increases in state, local and private debt!

STATE, LOCAL AND PRIVATE DEBT, PERCENT CHANGE FROM YEAR AGO

Now in one sense, money is money. Your buying on your credit card creates debt/money, just as federal deficit spending creates debt/money. Presumably, both should have the same stimulative effect on the economy. They do, but not long term. Why?

Because, unlike the federal government, you, your business and local governments cannot create new money endlessly to service your debts. Your debts can pile up to the point where you must liquidate them by paying them off or by going bankrupt. When non-federal debts become too large, a growing number of people, states, cities and businesses must pull back and stop further borrowing, i.e. stop creating money, or even destroy money by paying off loans. When that happens, we have a recession.

(As an aside, this is one reason the early stimulus efforts had so little effect. People used the stimulus money to pay off loans, so while the federal deficit spending created money, the loan pay-downs destroyed it. Debt reduction destroys debt/money.)

During the recession, and for a short time after, we tend to cut back on our personal borrowing and liquidate debt/money. Then we begin to resume borrowing, more and more, until again, we hit our personal limits and cut back, causing yet another recession. The sole prevention of this cycle, which averages about 5 years in length, is to make sure that federal deficit spending grows sufficiently to offset periodic money destruction by the private sector.

In summary, federal deficit spending is good for the economy, always good, endlessly good (up to the point of inflation). Private and local government spending/borrowing also is good, but not endlessly. Unlike the federal government, the private and local-government sectors eventually reach a point where debt is unaffordable and unsustainable.

To prevent recessions, the government continuously must provide stimulus spending, then provide added stimulus spending to offset the periodic reduction of money creation by the private sector.

__________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

These data call into question the popular belief that encouraging bank lending stimulates the economy. While short-term effects may be positive, long-term bank lending seems to lead to recessions, as servicing loans becomes ever more onerous for the monetarily non-sovereign sectors. In contrast, Federal deficit spending easily is serviced by the government, and therefore is preferable to private borrowing as a stimulus.

__________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Rodger Malcolm Mitchell

http://www.rodgermitchell.com

![]()

==========================================================================================================================================

No nation can tax itself into prosperity, nor grow without money growth. Monetary Sovereignty says: Cutting federal deficits to grow the economy is like applying leeches to cure anemia.

MONETARY SOVEREIGNTY

Excellent post. I agree.

LikeLike

Nice work bill. Very helpful. Like you mention the currency issuer plays a critical role during the bust periods. The underlying cause of the boom/bust cycle is the poor structure of our banking system. Our banking sector needs to be structured for transparency and stability to remove systemic risk. All the stuff warren talks about like not letting private banks sell off their loans and requiring real assets as collateral. You do that baby and we gots ourselves a winner

LikeLike

Thanks Dollar,

There is a Bill Mitchell and a Rodger Mitchell, and though both understand Monetary Sovereignty, ne’er the twain has met. Yet.

I suspect there is an even more fundamental problem than bank sector structure. The data seem to show that non-federal borrowing inevitably grows until it becomes unsustainable, at which time we have a recession.

Perhaps, tougher loan requirements might help, though.

Rodger Malcolm Mitchell

LikeLike

Roger – of course your not Bill my mistake

Hell yeah the data shows it…all Wall Street has been doing is making bubbles. Moral hazard is introduced to non-federal borrowing as soon as the banks can sell of their loans.

LikeLike

Oh that’s funny… I’ve visited verbose Bill before, but this is my first visit to concise Rodger’s blog. Good post, sir.

“I suspect there is an even more fundamental problem than bank sector structure.”

The problem is in the money itself, isn’t it? In the balance between money created by the private sector, and money created by the ‘monetary sovereign’?… The factor cost of private-sector money is borne fully by the private sector. The factor cost of the government money is only fractionally borne by the private sector.

It is cost, I think, that underlies the unsustainability of debt growth.

ArtS

LikeLike

The Arthurian,

In reality, federal money creation costs the private sector nothing. Taxes don’t pay for federal deficit spending, which is how the government creates money.

The point of the post was that while federal T-securities are unnecessary and infinitely sustainable, private sector borrowing is only minimally sustainable. When it reaches its limits, it reverses, and we have a recession — unless federal spending picks up the slack.

Unfortunately for America, Congress equates federal finances with personal finances, thereby guaranteeing continual recessions and personal suffering. Even sadder: The public believes it must suffer. Some sort of universal guilt complex, perhaps.

Rodger Malcolm Mitchell

LikeLike

Hi, Rodger. That was a quick reply!

“Taxes don’t pay for federal deficit spending”

Maybe, but I’m not there yet. Anyway, I have something else:

Your third graph contrasts Federal debt (red, blue) to Non-Federal debt (tan), displayed as percent change from year ago.

That’s fine.

Your fourth graph takes the percent change in total debt, and subtracts from it the percent change in federal debt. You are showing me a difference in percent changes, which is not the same as the percent change in a difference in debt.

Perhaps that’s what you intended, but it strikes me as odd. And it isn’t “STATE, LOCAL AND PRIVATE DEBT, PERCENT CHANGE FROM YEAR AGO” as the graph is labeled.

Here is a FRED of percent change in debt minus debt. Not as striking as yours, but it still shows downtrends starting before recessions.

Note the difference in the Y-Axis label, as compared to yours.

If I am out of line, step on me.

ArtS

LikeLike

Rodger,

Interesting post.

My Dad used to say the fractional-reserve banking system( the expansion of bank credits created as a multiple of deposits) simply does not work in reverse.

So that, as the beginning of the debt-deflation cycle cancels a fractionally-reserved (debt-based) deposit, the result is a contraction that is measured by the division of (opposite of multiplier) the credit-based assets serving as the money supply.

Thus, fractional-reserve banking is inherently, if not genetically, both pro-cyclical and parasitic.

But only to real people.

Thanks.

LikeLike

Your dad was correct, which is what the data in this post show.

I should mention that the so-called “fractional-reserve” system does not exist. Banks create reserves by lending, and if ever a bank is short of reserves, it simply borrows from the Fed or from other banks. No bank runs out of reserves.

The system more properly is called “fractional-capital.” That is the limiting factor.

That detail does not negate your Dad’s observation, however.

Rodger Malcolm Mitchell

LikeLike

Hey Rodger,

Roger that.

Our ultimate debate will be over whether the role of government ought to be to act through the price of the monopoly currency or the quantity of the monopoly currency, I believe.

But, in the meantime, my response vid to another MMTer on the endogenous money issue.

http://www.youtube.com/user/EconomicStability#p/a/u/2/9NUmpY854fg

It got cut short a minute. – being in reply to his video reply to ours on Turning Around a Balance Sheet Recession.

Towards monetary sovereignty – where ALL money is created by the sovereign’s government.

Best.

Joe

LikeLike

Art,

Federal taxes pay for nothing. State and local taxes pay for state and local spending. That is one difference between Monetary Sovereignty and monetary non-sovereignty.

Using the Warren Mosler scoreboard analogy. A scoreboard is “point sovereign.” It has the unlimited ability to post points. It never runs out of points. So it doesn’t use points taxed from players or spectators. Even if strangely, it did levy a “points tax,” it wouldn’t use those points. It would just destroy them, just as the federal government destroys tax dollars.

The U.S. is Monetarily Sovereign. It has the unlimited ability to create dollars. It never can run out of dollars. Having no need for tax dollars, it destroys them.

You are correct that a difference in percentage changes is different mathematically from the percentage difference in changes. There are many ways to show the data, some more visual than others. (It brings to mind the chestnut, “Figures don’t lie, but liars figure.”)

Here is a graph getting rid of all percentages and just showing absolute differences in changes — not quite a dramatic, but making the same point: Decreases in federal debt and increases in non-federal debt lead to recessions.

And here is a graph showing the percentage change in the absolute differences between total debt and federal debt:

Again, the same point: Federal debt, good. Non-federal debt, temporarily good, but leading to recessions.

Rodger Malcolm Mitchell

LikeLike

Hi Rodger,

Have you studied China in this same respect? I’d be very curious to see how the fact that they are somewhat pegged by a band, limits them in anyway, and if the effects (if there are any) are soon to be felt, how it could effect other countries that trade with china etc.

cheers

LikeLike

Have not studied China. However, being what amounts to a dictatorship, they can be as Monetarily Sovereign as they wish to be.

LikeLike

It would seem though they are doing the right thing though, they are raising rates in light of higher inflation

LikeLike

There is something perverse about the way mainstream economics worries (panics?)about the debt that doesn’t matter – Federal Government, yet has been blase about the debt that does matter – private – the massive build up of which has caused the current crisis, because of a belief in the impossiblity of rational markets misallocating debt. Even worse, it looks like most “rescue” attempts are aimed at re-starting the sort of private borrowing that has gotten us into this mess.

My takeaway from this, is that federal governments should spend more so that the private sector doesn’t have to borrow so much, and hopefully curtail the tendency for private banks towards usuring the population.

LikeLike

I like your takeaway.

The perversity you mention is even worse than you said. The old-line economists actively support efforts to increase private borrowing, while actively supporting efforts to decrease federal deficit spending.

What could make less sense than that?

Rodger Malcolm Mitchell

LikeLike

It makes perfect sense. Debt-fueled consumerism is exactly what TPTB needs to turn people into slaves.

LikeLike

TPTB – The Powers That Be

Saving people insufficiently acquainted with plutocracy conspiracy theorists from having to google the acronym. (This does not imply that there isn’t such a conspiracy.)

LikeLike

joebhed,

“Our ultimate debate will be over whether the role of government ought to be to act through the price of the monopoly currency or the quantity of the monopoly currency, I believe.”

Government does both. It determines the quantity by its spending. It determines the price through interest rates.

Also, as I explained earlier, even a 100% reserve requirement would not limit bank lending. Heck, even a 200% reserve requirement wouldn’t do it. Bank lending is not limited by reserves. So-called ‘fractional reserve” lending does not functionally exist. A bank with zero reserves could lend billions, depending on its capital.

Let’s say a bank has zero reserves, and there is a 100% reserve requirement. It lends $1,000. Instantly, that $1,000 becomes part of its reserves. So the bank meets the 100% requirement.

Then let’s say, the borrower writes a check, and some of that $1,000 disappears from the banks reserves. No problem. The bank gets what it needs from the Fed window, from other banks or from the public. I myself owned a company that lent banks millions of dollars every night (for reserves), and reclaimed the money in the morning.

The only thing that limits bank lending is bank capital. So let’s forget about reserves. They are meaningless.

Now, if the point of that video was to say that banks should not lend anything, we have a problem. Where should new businesses get money? From private lenders? Perhaps, but then private lenders merely would be doing bank business, and you’re right back where you started.

Or if that’s not your point, what is?

The point of my post is that federal deficit spending creates long-term growth, while bank lending can create short term growth, but must be supplemented by federal spending when the bank loans come due.

Rodger Malcolm Mitchell

LikeLike

OK, Rog, I’ll bite.

Thanks for watching, though.

I thought the point of the video was clear enough that under full-reserve banking, banks could lend their entire savings/investment deposit portfolio – so banks could lend today’s entire bank-credit based money supply – MINUS the amounts that depositors identify as demand deposits. They can lend no more than that.

Is there a problem?

I think government does neither now.

The private Fed’s OMC operations attempt to determine the non-inflationary quantity of money by setting target interest rates – poorly.

How does the government determine the money supply through its spending? What about bank credit expansion, or contraction?

Having read Modern Money Mechanics over 30 years ago, I have always known that banks DO true up their required reserve positions – always have.

Either cash, inter-bank or Regional-bank collateral borrowings.

The legal requirements for reserves have not gone away, only been watered down through deregulation over that time in what counts in the numerator and what counts in the denominator.

Please see: http://www.federalreserve.gov/monetarypolicy/0693lead.pdf

If you’re telling me that some regulation exists that exempts bank examiners from ensuring that the existing reserve maintenance requirement is met by reserve true-up, then please tell me what that is.

The fact that there are many ways to achieve the requirement today does not make the reserve requirement non-existent.

Under fractional-banking, everything from 0.1 percent to 99.99 percent reserve requirement requires there be a reserve on bank examiner day.

Were reserve requirements over 100 percent, that would disallow the lending of depositors’ money and be unnecessarily deflationary.

Where did you show how banks with a full-reserve requirement could increase the money supply beyond its savings base? I missed it.

Or I don’t understand it.

By full-reserve banking I mean as contained in the Kucinich Bill,, or in Irving Fisher’s 100 Percent Money book or in his central banking proposals for full-reserves from many economics textbooks, notably in Chapter 10 of L. Ritter’s Money and Economic Activity(Houghton/Mifflin)

Thanks.

LikeLike

The fact that banks “true up” to reserves is irrelevant to the point I made. The reason bank lending is not limited by reserves is because banks can get all the reserves they want, any time they want.

It’s like saying bank lending is limited by the amount of water in the ocean. Banks never run short of reserves. If they need reserves, they get all they want from the Fed, from other banks or from the public.

That is why a 100% reserve requirement would not limit lending. Even a 200% reserve requirement would not limit lending. Reserves are freely available to the banks. What kind of limit is reserves, if reserves themselves are available in unlimited amounts???

That “true-up” you mentioned is merely a balance sheet operation that does not limit lending. It’s just end-of-day accounting reconciliation.

So what is the limiting factor for lending? Bank capital.

Also, you asked, “How does the government determine the money supply through its spending? What about bank credit expansion, or contraction?”

Federal spending increases the money supply as does bank lending. The difference is, bank lending must be repaid. Fed spending does not need to be repaid. When bank lending is repaid, it leads to recessions, unless federal spending picks up the slack.

Rodger Malcolm Mitchell

LikeLike

The limiting factor is bank capital only if there are regulations limiting lending to a multiple of that.

The market limit is the number of borrowers in good standing available who are prepared to take bank loans on the price currently offered.

So it is the price of reserves, not the quantity, that matters since it partially influences the current price of loans on offer.

One of the reasons the Fed can expand its balance sheet as much as it wants is that it is not limited by capital regulations and its ‘borrower’ (the Treasury) is always in good standing by the simple fact that it owns the central bank. And the ‘price’ of money doesn’t matter in this instance because whatever the Fed charges the Treasury comes back to the Treasury in bank profit. The price to the Treasury is always zero.

So that’s another way of showing that central bank money is effectively Free.

LikeLike

Sorry, Roger, you are way off base here.

I guess we should pursue the issue, for clarification.

Your claim that “ banks can get all the reserves they want, any time they want. “ is ONLY true under a fractional-reserve banking system

But you ask this question – “What kind of limit is reserves, if reserves themselves are available in unlimited amounts??? ”.

The question, Roger, should be “ARE, or ARE NOT, reserves available in unlimited amounts under a full-reserve banking system?”.

The answer is they are not.

I am a little surprised at your misunderstanding of full-reserve banking.

I gave three bases for full-reserve banking, and your conceptual here – oceans full of reserve water – is antithetical to all of them.

You are using the “fractional-reserve” system as a basis for what happens in a full reserve system. Does NOT compute, sorry.

Under a full-reserve system, bank lending IS CONSTRAINED to its savings-deposit base, as full-reserve banking can only happen AFTER all bank-credit (fractionally-reserved) demand deposit money has been monetized into “real” money.

Again, if you read the Kucinich Bill, you could see that the “water in the ocean” statement here is pure folly.

Again, if you read Fisher’s 100 Percent Money book, the same.

Again, if you read Chapter 10 of Ritters book, on Central Bank Reserve Requirements, the same.

And, if you read the 1939 Program for Monetary Reform, written by six of the most prominent academic economists at the time, and publicly supported by over 400 economists, the same.

You can’t just parley the MECHANICS of the fractional-reserve banking system into a fully-reserved system just because you say so. It does not work that way. Oceans full of water notwithstanding.

There would be no such thing as going out and acquiring reserves.

Everybody’s reserves equals everybody’s deposits.

The ONLY way to get more reserves is, DA DAH, get more real money.

This of course does broach the question: Then from where does additional money come for growing the economy?

The provision of new money, of course, becomes a government prerogative.

As in, monetary sovereignty.

Thanks.

LikeLike

Joebhed,

I guess I should begin by questioning a program proposed back in 1939 and endorsed by 400 economists and by politicians. Today, we have thousands of economists and politicians who endorse the ridiculous notion that the federal debt is too large, so you know my opinion of these people. If they understood economics, I would not be writing this blog.

Anyway, you are correct if, and only if, banks are not allowed to obtain reserves from the discount window, from other banks or from the public. Were that to be the case, bank lending would not be restricted even to 100% of reserves, but to far less than 100%.

Because banks cannot control the amount of their reserves (the depositors do), full reserve banking automatically would devolve to a reverse form of fractional reserve banking.

Today, banks lend 10 times reserves, and under a full reserve system banks probably would lend no more than 1/2 reserves — so bank lending could be reduced to 1/20th of its current level or less.

What is the goal? To limit bank lending? If so, why? The amount of bank lending was not the problem. It was the quality of bank lending that precipitated the recession. Bad mortgages would not be eliminated or even reduced by full-reserve banking.

Far better for bundling and reselling of mortgages to be outlawed, and for banks to assume responsibility for their own loans.

By the way, what does this mean: “. . . demand deposit money has been monetized into “real” money”?

Rodger Malcolm Mitchell

LikeLike

Thanks, Rodger.

Let’s start off with the last question first,.

What does monetization of demand deposits mean – then why is it important to understand?

In order to transition TO full-reserve banking, you first need a mechanism to transition FROM fractional-reserve banking.

That mechanism is monetization, in the real sense of the word.

In Fractional-reserve banking, as in the Fed’s Modern Money Mechanics publication, it is the “demand-deposits” that end up being multiplied into new bank-credit money – requiring reserves. Only the Demand Deposits.

IOW, Savings Account deposits are, by definition, 100 percent reserved, as they represent already-created real money being saved. There is only one claim on savings deposits, not multiples, thus no money “multiplier” is in effect, needing repair to achieve stability.

Thus, the removal of all risk to the banking system, the currency system and the national economy(TBTF) is enabled by transitioning the “bank-credit” money (money created by multiplying demand deposits) into real money.

It is monetized by the central bank, nationalized under Treasury (Kucinich)

On that date certain, ALL monies become real monies.

These principles have been laid out at least since Soddy and Fisher when money was printed currency tied to gold. Thus the “monetization” back then was through the printing of currency to replace the non-currency M1.

Today, with electronic money, the methods are simpler, requiring only the legislative mandate for the transition.

Please see

SEC. 402. REPLACING FRACTIONAL RESERVE BANKING WITH THE LENDING OF UNITED STATES MONEY.

of HR 6550, the Kucinich Bill, for further explanation.

If you understand that, Rodger, then your other points are more easily addressed.

Such as, yes, if they had ADOPTED the 1939 Plan, we would HAVE monetary sovereignty, and we could both be off sailing somewhere.

Yes, depositors determine bank balance sheets, and therefore loan policies, putting depositors in greater control of the banking system – more Co-op Banks, more Credit Unions.

Banks COULD lend up to ALL of their non-demand deposits, but WOULD not for one reason; we would not be dependent upon banks for a money supply, only for loans. Your statement about 1/20th shows a remaining lack of understanding the function of reserves WITHOUT fractional reserve banking. Think about it a little more. Banks could only lend real money, but they could lend ALL of their real money without restriction. Maturity-matching would become the hallmark of sound banking.

What is the goal? Economic, financial and monetary stability is the goal. It is achieved by removing the pro-cyclical nature of fractional-reserve banking from the national economy. You should really read the 1939 Program to understand the sound economics behind its proposal. Then you can criticize it all you want, for good reason.

Thanks.

Joe

LikeLike

“The provision of new money, of course, becomes a government prerogative.”

No it doesn’t because they would lose control of the monetary policy interest rate.

If there is demand for borrowing then the scare deposits will be bid up to crazy levels and the economy will collapse due to the interest rate imbalance or a lack of credit for investment.

So the government then has to supply liquidity to maintain the credit flow – just as it does now at pinch points

And most importantly it assumes nobody cheats. Anybody who understands the history of coin clippers and why fractional reserve came about in the first place knows that everybody cheats if they can – particularly bankers.

I doubt that full reserve is any easier to police than fractional reserve or no reserve.

LikeLike

Hey Neil,

With all due respect here, I fundamentally disagree.

That’s my point.

If you read my first or second comment to Rodger, I said that ULTIMATELY we would argue over whether the interest rate mechanism or the money supply mechanism would prevail in a real sovereign money system.

Your comment proves my point.

Yes, I am a monetarist, and a monetary nationalist, thus seeking monetary sovereignty through the nationalization of the money system, not the banking system.

There is no need for the government to control interest rates, assuming an adequate supply of money in existence to achieve GDP potential.

There would be no bidding-up war on interest rates by bankers, there would be a bidding- down war on interest rates by borrowers.

Money would not come into existence as a debt – it would come into existence to provide the means of exchange for the national economy’s product.

The centrally-controlled monetary policy interest rate is a relic to fractional-reserve banking. It becomes as unnecessary as it is ineffective.

Why are there scarce deposits? ALL money is deposited UPON CREATION.

Create enough money to achieve GDP potential and scarcity becomes an ineffective tool for economic manipulation.

Why is there a lack of credit? Because you assume so?

The government DOES supply liquidity – that becomes its main monetary authority function. Have you read the Kucinich Bill?

Have you read Dr. Yamaguchi’s work on modeling the transition to debt-free money?

Your doubts about full reserve banking seem very ill-founded. There is no reserve requirement with full-reserve banking.

We re-define the legal contract between depositor and banker.

Banks are prevented from creating money – PERIOD.

Banks are only legally allowed to lend money they have in their accounts – PERIOD.

The government is responsible for creating the money for its national economy and it manifests through the budgeting process.

Please have a view of this video: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=oWEhKcsofQ4

It’s Not a Deficit, It’s New Money.

It’s aimed at progressives and neo-chartalists.

Then, let’s chat.

Thanks.

joe

LikeLike

Joe, If a bank lends 100% of its deposits, then depositors start to take money from their accounts, what does the bank do?

Rodger Malcolm Mitchell

LikeLike

Rodger,

Thanks.

Banks pay no interest for, and cannot lend, demand deposits.

Banks must pay interest for, and can lend, non-demand(term) deposits.

All term deposits are CD-like in nature.

There is a contract that the money belongs to the bank for its use for a term certain(maturity), but there would be provision (Penalty) for early withdrawal type of thing.

Thus my comment that sound banking will be marked by maturity matching.

IF a savings depositor withdraws its money to a checking account, then the bank only needs to make it up if it has lent 100 percent of its term deposits – again highly unlikely as money is created(deposited) without debt. Otherwise, it uses its un-lent deposits, or by borrowing from across the street.

Either way, non-demand deposit money is always LENT to the bank.

Either way, the amount of money in savings and investment accounts is always known as a matter of magnitude, assuming the monetary authority is doing its job.

Again, the depositors are much more in control of the banking system than at present.

The diversity of depositors should result that manipulation of that power is never a problem.

Hopefully, this shows why the arcane interest rate control is totally unnecessary as a monetary policy tool.

Today, there is more debt than money.

Tomorrow, there will be more money than debt.

Thus, the natural interest rate becomes zero.

Have you seen Dr. Bernd Senf’s work on The Deeper Roots of the World Financial Crisis?

Clue: Yes, it’s the private, non-sovereign, debt-money system.

Thanks.

LikeLike

Every form of money is a form of debt.

Rodger Malcolm Mitchell

LikeLike

Every generalization is wrong.

LikeLike

Can you name a form of money that is not debt?

Rodger Malcolm Mitchell

LikeLike

Coins, perhaps?

“the coins in your pocket are legal tender and yet were not issued against debt. They’re minted by the US Government, backed only by the gilt-edged credit of the American people, no one is paid interest on it and they don’t add a penny to the statutory debt.” — beowulf

LikeLike

Getting too small to read!!

Can I name a form of money that is not debt?

I distinguish between money I have to pay interest on, and money I don’t have to pay interest on.

In a footnote, Keynes wrote: “we can draw the line between “money” and “debts” at whatever point is most convenient for handling a particular problem.” So Keynes was willing to admit that money is debt. But he also understood the importance of distinguishing between the two.

The difference is cost: The cost of interest.

Yes, I can give it a name. Money that circulates without interest cost is “money”. Money that circulates *with* interest cost is “credit”. The record of credit in use is “debt”.

Cost is the key.

LikeLike

Love it.

I said every form of money is debt and I receive a “clever” message that every generalization is wrong. So I ask the clever guy to name a form of money that is not debt, and I receive a bunch of double talk about Keynes saying it is and also isn’t, plus invented nonsense about paying interest.

Let’s see if I can make this simple enough. On page http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Money_supply there is a list of types of money. Which of those is not debt?

Note to Joe: Fiat money would have no value, were it not debt. Think about it before you tell me again about Kucinich.

(If I seem a bit testy lately, it’s because I’ve been getting dopey responses from closed-minded people who would rather argue than think. Guys, I’m not impressed. Please don’t just make stuff up.)

Rodger Malcolm Mitchell

LikeLike

Unless I do not understand what you mean by debt free money, all the following should prove that debt free money is rea:

colonial script

company script

allied military currency

spartan iron money

roman leather money

cowry shells

tool money

wampum

tally sticks

continental currency

greenbacks

LETS

emergency stamp script…..the worgl for example

nazi labor treasury certficates

most if not all stamped metal coins in history

salt

cows

isle guernsey money

Value of money is subjective whether it be gold, credit or cow dung. Money is a purely social construct based.

LikeLike

Barter can be debt-free. But money is a replacement for barter. It’s intrinsic value generally is less than its money value.

So what gives money its value? What gives a dollar its value? Answer: Full faith and credit. A dollar bill is a federal reserve note.. The words “bill” and “note” designate debt (as in T-bill and T-note). It is a piece of paper that says the holder is owed full faith and credit by the federal government.

See: https://rodgermmitchell.wordpress.com/2011/06/20/why-a-dollar-bill-is-not-a-dollar-and-other-economic-craziness/

Rodger Malcolm Mitchell

LikeLike

Rodger,

If that statement about all money is debt was meant for me, then I’m inclined to say, like endogenous money – So What?, but rather I’ll just say that had the 1939 Program been advanced, no money would be debt-based.

But since Bretton Wodds, GATT and their successors, ALL money is a debt.

Or you can’t play here.

So what?

If we reform the money system along the lines in the Kucinich Bill, then again, all money will be based on national economic wealth.

Debt-free at issuance.

And that repairs the problems identified in Dr. Senf’s truly amazing work.

LikeLike

Sorry, it’s not a silver bullet

100% reserve banking just ends up like 0% reserve banking except that the central bank has to ‘monetise’ the entire loan book rather than handing over an insurance certificate.

At the moment the power to create money is delegated to the banks based on regulations of capital adequacy. It’s a distributed system that responds rapidly to the changing needs of the economy.

There is very little operational difference between the two structures. In a sovereign money system with a fiat currency the central bank can always deal with a maturity transformation disaster.

You put the bank into administration, make sure the bank investors take the full loss, refund the insured depositors, sell the good bits that are left to other market participants and write off the bad bits.

The problem in the recent collapse is that the central bank and the government didn’t realise they were monetarily sovereign.

LikeLike

A money form that is not debt? What about common stock? People with capital including skills and labor could form a company and issue common stock. That common stock could then be accepted for the goods and services of the company. I don’t see any debt.

Also, government fiat can be issued debt free unless you argue that the debt is owed by the taxpayers.

LikeLike

Stock is not money. Just because something has value doesn’t make it money.

Government fiat is a debt of the government. The government owes the holder of dollars full faith and credit. I’ll quote from a previous post: Why a dollar bill is not a dollar

Rodger Malcolm Mitchell

LikeLike

Rodger,

On the 9th you said, “In reality, federal money creation costs the private sector nothing.”

If that is true, then federal money is not debt.

On the wiki chart, each of the categories is a “line” Keynes might have drawn, dividing money from debt. Money is on the left. Debt is on the right. As one moves from left to right, the factor cost of money increases.

This graph also shows the Keynesian distinctions:

Thank you for noticing that my thinking is sometimes original. I am quite good at it.

ArtS

LikeLike

Rodger,

To be clear here, because I feel a digression afoot.

Way above you mentioned the other Mitchell, Prof. Bill.

Among the neo-Chartalists, Bill advocates very strongly on his blog for debt-free money.

Please realize that Bill’s oft-suggested direct government payments of deficits to meet public purpose goals(full-employment) without issuing debts means that the pushing of the keystroke that deposits those balances in bank accounts of people and businesses that receive government services happens without creating any debts. It is debt-free money creation as we mean it in our reform proposals.

Also Warren Mosler proposed the same for a Trillion Euro bailout over a year ago on his blog. In response to a question I put to him – No, there would be no debt issuance.

As i said, today, due to Bretton Woods and other international financial constrictions, that Bill would also call unnecessary and voluntary constraints, all money IS debt.

But, so what?

LikeLike

“Afoot”? Cripes, I’ve just lost a century.

Anyway, I too favor not issuing T-securities. I said so 15 years ago. But that does not change the fact that all money is debt, and must be debt. There cannot be debt-free money, though there is no need for federal issuance of T-securities — two totally different concepts.

Rodger Malcolm Mitchell

LikeLike

Rodger,

Again, I’ll bite.

I gave two examples of MMTers who advocate the issuance of debt-free money. There are several others I know of.

As do we at the Kettle Pond Institute.

I did so because you often use MMT theory in your work.

Understanding that should be adequate to promote the acceptance, of the concept of debt-free money.

Your guys support it – up to a point.

As far as that goes, you know I am critical of MMTers because it does not go far enough.

IF you say that all money must be debt, then you need to talk to Bill and Warren, because under their proposals there is no basis for that claim.

They both propose creating money without debt.

What stands behind the T-bill now would be what stand behind the debt-free issued dollar – the full faith and credit of the GOVUS and the full potential of its national economy.

Google up The Muscle Shoals Project, Henry Ford and Thomas Edison.

You say you agree that a monetarily sovereign government should not issue debt.

So then, how should the sovereign issue its money?

Please explain the separation line that you see for these two concepts of sovereign money.

Thanks.

LikeLike

Joe,

You are mixing two separate ideas:

Idea 1. There is no need for a Monetarily Sovereign government to create T-securities and exchange them for currency (aka “borrow). I agree with Bill and Warren on this. (Since I wrote it 15 years ago, should I say they agree with me?) A Monetarily Sovereign government cannot borrow its own currency.

Idea 2. All dollars are a form of debt. The government owes the holder of a dollar bill full faith and credit, which I describe at Why a dollar bill is not a dollar Important that you read this.

Look at all the forms of money listed at http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Money_supply. Each is a debt of some entity. Bank accounts are debts of banks. Money market accounts are debts of money markets.

Every form of money is a debt. There is no such thing as debt-free money. Debt gives fiat money its value.

Rodger Malcolm Mitchell

LikeLike

Rodger

I read that. It’s another place where you use Mosler.

It says that IN A DEBT_BASED money system, all money is a debt.

Why would you think I disagree with that?

As I’ve sent you my vid link where I discuss where GREENBACKS(debt-free money) get their value, what you can readily see is that its from the same place as the debt-based money– the government’s full faith and credit (even with electronic money) and the resources available to the national economy.

If you followed the Muscle Shoals link, it is said thusly:

“If our nation can issue a dollar bond, it can issue a dollar bill. The element that makes the bond good makes the bill good. The difference between the bond and the bill is that the bond lets the money brokers collect twice the amount of the bond and an additional 20 per cent, whereas the currency pays nobody but those who directly contribute to Muscle Shoals in some useful way.”

” …. if the Government issues currency, it provides itself with enough money to increase the national wealth at Muscles Shoals without disturbing the business of the rest of the country. And in doing this it increases its income without adding a penny to its debt.”

So, Roger, IF THERE’S NO DEBT ISSUED, it’s debt-free money.

If they create $30 MM debt-free dollars to pay the labor and concrete costs, that money not only enters the economy without creating a debt being owed to anyone, it remains in the economy as part of our permanent money system.

Which is what we’re all about – understanding and remedying the defects of the debt-based money system identified by Robert Hemphill at the Atlanta Fed.

And again, it’s what Bill and Warren and others have proposed.

All money does not need to be, and should not be, a debt.

And since you now say it is a “form” of debt, and that form of debt does not add a penny to anyone’s debt, as the article says, are we devolving into semantics?

Joe

LikeLike

Not semantics, Joe, sophistry.

You said, ” . . . IF THERE’S NO DEBT ISSUED, it’s debt-free money.”

What you call “greenbacks” are known as dollar ib>bills. On these dollar bills is printed, “Federal Reserve Note. The words “bill” and “note” signify debt instruments as in “T-bill” and “T-note.” Greenbacks are debt instruments; the government owes the bearer full faith and credit.

So-called “federal debt” is the total of outstanding T-securities, which are unnecessary, even harmful, in a Monetarily Sovereign nation. As I’ve said for 15 years, the government should stop issuing T-securities.

Here is the point you may misunderstand: There is no functional relationship between federal deficit spending (aka “money creation”) and T-securities, which exist as a matter of law, but not as a matter of function.

We could have deficits without debt and we could have debt without deficits. That is, we could have deficit spending without T-securities, and we could have T-securities without deficit spending. There is no functional connection between the two. Functionally, the “federal debt” is not the total of deficits, a point often misunderstood.

The concerns about the size of what is misnamed “federal debt” are silly. Federal debt could be eliminated tomorrow, simply by crediting the bank accounts of T-security holders. No T-securities = no so-called “debt.”

But if all T-securities disappeared, all money still would be debt. Even if you eliminate banks, bankers, bank lending, non-bank lending or lending to your cousin, you can’t eliminate debt so long as there is money. Why? Because:

All money is debt.

Rodger Malcolm Mitchell

LikeLike

Rodger

Fact: Under the fractional reserve banking system, Dollar Bills are not debt-free Greenbacks as in my examples and definitions, and as in the Kucinich Bill

Under fractional-reserve banking, Dollar Bills come into existence AS A DEBT.

Only coins come into existence debt-free.

So, what it says on a FRB dollar bill matters not to any discussion I am having.

Now, under the Ford/Edison proposal for Muscle Shoals, the Treasury would have BEP print up the Dollar Bills and Treasury pay them directly for services received on the project.

THAT would be a Greenback DEBT-FREE at issuance dollar bill

The first recipient/user of the Greenback DEBT-FREE Dollar Bill is the laborer who deposits it in the bank.

It is NOT a debt-instrument and all the government owes the bearer upon distribution is acceptance of payment in kind.

(It is not the FR member bank who collateralizes it with the Regional Fed).

Subsequent bookkeeping notwithstanding.

And I never said anything about deficits and debts.

I have no such misunderstanding.

But your statements here about having deficits without debts(functionally speaking) belie the very real, very legal fact of the Government Budgeting Constraint(GBC), and are based on MMT, which is only a theory capable of becoming operational by changing many of the laws of the land, including the GBC.

Which, by the way, the Kucinich Bill DOES.

At the Fiscal Sustainability Teach-In I asked Bill and Warren for a list of all the laws that need changing in order to move from theory to reality.

Still waiting.

As I am for your explanation of how your sovereign creates money.

Nuff said..

LikeLike

Authurian,

Your cite is talking about the fact that the Treasury is not required to issue T-securities (i.e. “debt”) in the amount of coins issued. So they aren’t counted in the total of outstanding T-securities, which is misnamed “federal debt.”

However, the coins themselves are a debt of the federal government, just like paper money. If they weren’t a debt of the government, they would have no value.

There was talk recently about Obama doing an end run around the debt ceiling by issuing a $1 trillion dollar coin and depositing it in the Federal Reserve Bank. The bank could issue money against it, and none of that would involve T-securities, so there would be no increase in the so-called “debt.” Legally that would work, but Obama does not have the courage.

See how nuts things become when people who don’t even know what debt is, argue against debt?

Rodger Malcolm Mitchell

LikeLike

Dunno how I missed this thread. Rodger: these are all good guys. They just haven’t made the key conceptual leap, though they are getting asymptotically close.. Your points can’t be made often enough. In their defense, I don’t think most in the know emphasize the centrality of the “money is debt” point nearly enough.

Money is debt the way green is a color. Money is a type of debt. Money is not and cannot be “debt-based”, “backed by debt”, “analogous to debt”, it IS debt. “Money” is definable in terms of the more fundamental concept “debt” [or “credit”, which just means “tbed”; “debt” means “tiderc” 🙂 ], not vice versa. If people read some MMT or monetary sovereignist or circuitiste or creditary or institutionalist or post-Keynesian economist and think the economist has proposed debt-free or non-debt based money, it just shows the reader is not using the words “money” or “debt” properly (or more rarely, the economist).

Of the leading MMTers, Wray is the one who most frequently and clearly makes the point that money is debt and quotes past thinkers who explicated it like his teacher Minsky & Alfred Mitchell-Innes. Edison understood that money is debt – he says so in that quote! So did FDR. Dollar bills and coins are nothing but debts from the government to the holder. (Or rather, they are physical indicators of such a debt.)

Thinking about currency and coins as “not debt” is as crazy, pointless, unscientific and confusing as it would be to operate with $5 bills as normal, but to have a theory that insists that $1s, $20s, $100s etc are all money, BUT NOT THOSE EVIL $5s!!

LikeLike

Cal,

The problem is they seem so different. Money is good and debt is bad. And when I have money, I don’t have debt — or don’t think I have. I can be in debt, when I’m not in the money. To most people, debt and money are exact opposites.

Semantics kills economics because, unlike other sciences, economics does not have an agreed-upon lexicon, but rather has borrowed some words from common, inappropriate usages.

In other sciences, the practitioners want very specific meanings, as witness the argument about “planet” in astronomy.

Rodger Malcolm Mitchell

LikeLike

I agree that it is all about semantics, and the horrendous state of it in economics.

Most people’s understanding isn’t all wrong – money and debt are, can be exact opposites. The dollar bill paid and the tax debt extinguished by it are the exact opposites of one another. The bad way of thinking of money and debt is that they somehow aren’t even completely in the same universe. It’s incoherent, it doesn’t make sense, at best it turns into describing some kind of static barter economy that never existed anywhere.

At a high enough, deep enough level in any science, the real progress is always in the definitions. It’s always philosophical, it’s always semantic – dare I even say metaphysical?. Once you get these usually trivial definitions and concepts straight and understand in your gut what you are saying, everything else is easy, natural and obvious.

Problem is that sometimes science goes backwards, because people stop reading the books that make everything easy, which usually get a reputation as unreadable, filled with useless nonsense or pointless verbiage – especially when they are superconcise. Or the “trivial” things that “everyone knows” are only explained behind closed doors, but nobody really writes them down, because they are too trivial and unoriginal – become things that everyone forgets after something else becomes fashionable for a while, and need to be rediscovered at great cost later.

LikeLike

But neither you, Cal, nor you, Rodger, provides a brief, clear explanation of your reason for saying “money is debt”. Cal, the more often you repeat that phrase, the more I want to say, “It depends what the meaning of the word ‘is’ is.”

I have offered what to me is a clear difference between money and credit-in-use: I pay interest on credit-in-use, and I do not pay interest on money. And (i’ll say it again, Rodger) debt is the record of credit in use.

I have also said things that you could point to and say See, this is what I mean but you guys never say that. Instead, you spell “debt” backwards and call it credit. I think you got nothin.

Show me what you got. Don’t refer me to Wray or anybody. Lay it out. You know, 25 words or less!!

LikeLike

I’ll make it easy. Name a form of money you feel is not debt, and I’ll explain why it is debt. There is a handy reference list, showing forms of money, at: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Money_supply

Rodger Malcolm Mitchel

LikeLike

Arthur: I’ve been writing a number of relevant blog posts which I haven’t yet published. Have not been up to finishing them.

In “Money is debt” “is” is used in the most ordinary way, in exactly the same way it is used in “green is a color”. The problem, as Rodger points out, is the unnecessary and wrong restriction and redefinition of the word “debt”. The reality, the right way is much simpler. The correct way is the way “debt” is used in ordinary language, and in accounting, in the real world, in all languages for time immemorial. Here I disagree somewhat with what Rodger said just above. The inappropriate usage here is coming from bad economics, which unfortunately has become probably the most widespread and lethal plague the world has ever seen.

I happened to have had a real life instance that refutes the redefinition of debt as something where “I pay interest on credit-in-use” while I was writing this. I was paying a credit card by phone, and the clerk presented me with an offer where certain purchases would have zero interest. That debt to the credit card company is real, as is the monthly payment in full for an American Express Card. I would be in a pickle if I never paid it (unless I was smart enough to die first), but by the incorrect definition is not debt.

People say they owe a debt to their parents for taking care of them as children, and they repay it when they take care of them when they are old. That is how “debt”, or its synonyms I wrote on your blog is being used. Everybody understands this meaning of “debt”. For now, I leave it undefined. That is the meaning in good economics. Money is a kind of this correctly understood “debt”, which is the same thing as credit, viewed from the opposite direction. Since credit/debt is a social relationship between two entities, so is money.

Money is just this kind of debt which is the usual, universal meaning of debt, but tradeable in some sphere, standardized by a unit of account, and with arithmetic rules for adding and cancelling. For instance, because Jerry is a very successful comedian, the debt Jerry owes Morty and Helen Seinfeld in Del Boca Vista is very valuable. One could imagine a society in a retirement home where such debts drawn on Jerry, denominated in “jokes”, were tradeable and the definitive money, so that Morty and Helen could use them to get anything he wanted that the other geezers had.

In the real world, the basic kind of money – like coins or government banknotes – is government debt, which has great value and tradeability because of the enormous power of the government to lay debts going in the other direction on other entities and collect on them.

LikeLike

Thanks Roger for pointing out that the issue of WHETHER money IS debt, and only a form of debt, has not been settled by economists for all the time of their being, my respect for Randy Wray notwithstanding.

I get a little testy I admit when misunderstood principles become laughable to “the learned ones” of MMT.

The concept of publlicly-issued, debt-free money DOES need the rigor of economic study, but not as from that of cal above.

First, may we monetary reformers say this: The concept of debt-free money is so extremely limited that perhaps it defies a casual perusal.

The concept is thus limited: it is ISSUED debt-free, directly deposited by the sovereign into a private bank account.

Now, if THAT is possible, then debt-free money is possible.

But, once in those private hands, machinations exist that end its debt-free existence.

Sort of.

Accounting wise – so it MUST BE.

Despite the fact that the Treasury just issued my Social Security check, and did so on the MMT-sanctioned principle that the GBC does not exist, the “money-must-be-debt” folks are not impressed.

Though I owe that money to no one and can turn it into any commodity I choose without creating any real offsetting liability, for some reason – that money is debt.

It is at the point of deposit, as our present system of money has succumbed to the fallacy of double-entry bookkeeping, that notable prognosticators of the “money-must-be-debt” school hail its presence as obviously falling on both sides of the T.

And thus, money IS debt.

And thus, ALL money is debt, even though it was created out of nothing,as the bankers do today, only without issuing a loan, in the debt-money system.

My attitude is this.

Who gives a shit how the bookkeepers see things, and bookkeeping-based economists as well.

You can’t dismiss the obvious benefits of debt-free money, even as Bill Mitchell and so many others call for the issuance of debt-free money, because of the myopic tendencies of the yet smartest kids in the class.

It is because MONEY COMES INTO EXISTENCE debt-free that we can end our government borrowing and pay off the national debt.

LikeLike

Joebhed:, Bill Mitchell is not calling for debt-free money – and neither are you. It’s like calling for a “colorless green”. As Rodger noted, and as in my reply above to Arthur, the problem is using the word “debt” incorrectly, in a weird, unusual way only taught by the bad economics that clouds everyone’s minds.

The money, “directly deposited by the sovereign into a private bank account” IS the debt. It is a debt of the sovereign to the private bank account holder. The account holder is the creditor, the lender. See my answer above – the problem is the truth is “so simple it repels the mind” . The trap is making things more complicated than they are in reality.

Of course you are right. The account holder don’t OWE nobody nothing. The account holder IS OWED something. The sovereign or the bank – to keep things simple, imagine the bank is part of the sovereign government – is the borrower, the debtor. I & Rodger and most MMTers do support more issuance of what you call “debt-free” money, i.e. just “printing money” or directly depositing it.

LikeLike

All,

I don’t really know why we’re having this ‘colorless’ conversation.

I started with Rodger over My Dad’s point that fractional-reserve banking(debt-based money) CAUSED the recession he was referring to, leading to a somewhat nuanced discussion of whether fractional-reserve banking is real or not – and it IS; and then whether in a full-reserve banking system banks can still create money – AND THEY CAN’T.

Then, in response to my call for a debt-free money system, Rodger said – ALL MONEY IS DEBT. And we have been around here ever since.

You guys(?) NEED to first be capable of understanding something as elementary as a national monetary system that IS based on a certain type of money-creation. Then we can have no meaningful conversation.

I already explained my total disgust with the double-entry-bookkeeping straight-jacket that keeps us from having that intelligent conversation, yet here we are with colorless greens.

So, has anyone read Del Mar’s History of Monetary Systems or his History of Money in America?

If so, then can we START from a national economy operating a national monetary system and go from there? How do we create the money?

And if we can’t, then it’s all meaningless.

I tried long ago to get Rodger to read a paper by noted Japanese economist Kaoru Yamaguchi,

Click to access yamaguchipaper.pdf

who will be presenting his paper

“On the Workings of a Public Money System of Open Macroeconomics”

to Congressional staff next week.

Roger refused, noting Dr. Kaoru is first of all an economist, and he compares fractional-reserve to full-reserve banking – and there is no such thing as fractional-reserve banking – in true MMT-endogenousness.

Since Dr. Yamaguchi clearly defines the workings of a national monetary system based on the borders between the debt-based money system of present and the debt-free money system of the future, he provides a framework for intelligent discussion.

It is about how the money is created and brought into existence – either as DEBTS by the Treasury and the private banks, or without debts, strictly by the government.

Now, Cal, you may say, and Bill Mitchell may say, that when he calls for “fiscal spending” of money that doesn’t exist in any form and OUTSIDE the government’s DEBT-borrowing constraint that he is NOT calling for debt-free money, but clearly he is under the meanings in my and Dr. Yamaguchi’s language of money systems.

I don’t want to argue about THAT.

I want to argue about whether (A.) Was my Dad (and Yamaguchi) right in explaining why the continued expansion of the debt-based money system caused this financial calamity, or not.

And, (B.) if so, then what TF do we plan to do about it.

The rest is peepeedickin, and I don’t have the time.

LikeLike

You guys(?) NEED to first be capable of understanding something as elementary as a national monetary system that IS based on a certain type of money-creation. Then we can have no meaningful conversation. We do understand this. We are for it!

Was my Dad (and Yamaguchi) right in explaining why the continued expansion of the debt-based money system caused this financial calamity, or not. Yes, your Dad (and Yamaguchi) is right. But what Yamaguchi calls “public money” is a form of debt. So some of his terminology and categories are not good. He writes about the “legal tender” aspect of “public money”. “Legal tender” has no economic importance whatsoever. Government “public money”/reserves/currency is not, is never, can not be created “from” Treasury debt/bonds/”borrowing”. They are just two kinds of government debt/money, that the government plays silly shell games with, whose main economic function is to sow confusion.

The rest is peepeedickin, and I don’t have the time. The thing is that understanding that “money as debt” makes everything SIMPLER and easier to understand, and saves time. IMHO, even the MMTers could drastically shorten their exposition and papers if they organized them correctly and conceptually.

Thinking of money as “not debt” means using an unusual definition of “debt” that makes everything needlessly much more complicated and confusing. Money, because it is debt, is not a “thing” like a wedding ring – it is a relationship between two entities, like a marriage. I looked at my trusty Oxford English Dictionary for “debt” – basically it just defined it by giving synonyms – but it is clear that the accepted English language meaning of the word has always been as Rodger and I and many good economists use it.

LikeLike

Joe,

Every form of money in M1, M2, M3 and L is a form of debt. When you name a form of money that is not debt, I’ll agree with your premise. As to a dollar bill, which is a federal reserve note, the words “bill” and “note” signify debt. The federal government owes the holder of a dollar full faith and credit.

Perhaps the confusion is this. If you are saying that federal T-securities are unnecessary, I wholeheartedly agree. The federal government does not borrow, does not need to borrow and in fact, cannot borrow, its own sovereign currency.

Exchanging T-securities for dollars (erroneously called “borrowing”) does not create a debt. It is an asset exchange. The debt already existed, because the government owes the holder of a dollar and a T-security full faith and credit. To quote from a previous post ( Why a dollar bill is not a dollar”):

So although the nature of money is to be debt, else money would have no value, the creation of T-securities not only is unnecessary, but harmful.

If you disagree perhaps you can answer one simple question: What form of money is not debt? Here are a few forms of money, from which you can select: Bills and coins, travelers’ checks, checking account deposits, savings account deposits, money market funds — or anything else you can think of.

So if money is not debt, which of the above is not debt? Name one, and I’ll debate it with you.

And yes, fractional reserve banking is real if it doesn’t bother you that no bank ever has, or ever can, run out of reserves, because:

1. Banks create reserves by lending

2. Additional reserves are readily available from the government or other banks. What banks can and do run out of is capital.

Rodger Malcolm Mitchell

LikeLike

Rodger

All you need to do is to start off your comment with –

IN A DEBT-BASED MONEY SYSTEM, ….

And then, start off every new paragraph with,

IN A DEBT-BASED MONEY SYSTEM, …

And then you could finish by saying,

If there IS any other form of money system possible besides a debt-based money system, then I have never really heard of it.

But I have, Rodger.

If you care to, then please have a read of the 1939 Program for Monetary Reform available here.

http://www.economicstability.org/history/a-program-for-monetary-reform-the-1939-document

In a fully-reserved banking system, with government-issuance of money without debt, you have a debt-free money system.

Best,

Joe

LikeLike

Joe,

Please don’t include your videos. This is not meant to be anyone’s Facebook page.

” . . . with government-issuance of money without debt, . . . ”

Five simple questions. In this “money without debt” society:

1. Is that money supported by the full faith and credit of the government?

2. Are there bank deposits?

3. Are there bank loans?

4. Are there bonds?

5. Are there CD’s, and/or travelers’ checks and/or money markets?

Rodger Malcolm Mitchell

LikeLike

Rodger,

Sorry about the video. Never again.

Actually I didn’t know Facebook was about videos.

Learn something new every day. Thanks.

If you read the Kucinich Bill, feeling I surely have sent the link, then you would know that all the answers are yes.

Except if #4 refers to government bonds, which would then be a no.

There is no necessity for issuing government bonds.

Ain’t that what monetary sovereignty is all about?

joe

LikeLike

Whether it is called “debt” or not, does anyone deny the right of the US Government to create and spend any amount of legal tender without borrowing?

LikeLike

Apparently our clueless Tea/Republicans and Democrats, equally clueless President and the supremely clueless old-line economists disagree with you. Thus, this blog.

Rodger Malcolm Mitchell

LikeLike

Joe,

I reviewed the “100% reserve system” paper (written while we were on a gold standard). Here are the key, highlighted by the authors thoughts:

Yes, increased federal deficit spending is necessary to grow the economy. I wish Congress and the President understood that. But . . .

1. Our Monetarily Sovereign nation does not need to borrow. Federal spending is funded neither by borrowing or taxing. One simple law change could end all federal “borrowing”: Eliminate the requirement that T-securities be issued.

2. Servicing T-securities is no burden on a Monetarily Sovereign government, which easily can service any amount of T-securities. The authors of the paper were unaware of that, because at the time, the U.S. was not Monetarily Sovereign.

O.K., history made this prediction look silly. The authors were unaware of what was to happen in 1971. Not so shocking. Happens all the time.

Rodger Malcolm Mitchell

LikeLike

Rodger,

First of all I am very happy that you have read the 1939 Program. We would all gain were you to read it over several more times.

It was the most eloquent statement made on what needed to be done to the monetary system for several generations, and it is incredibly valid today in its observations and its methods.

It is also a document that less than one percent of economics students read over the course of those several generations, to the detriment of us all. Notably excepted here would be Dr. Ronnie Phillips, one of the Levy Institute and Minsky School fellows.

You say the document was written while we were on a gold standard. Which gold standard would that be in mid-1939?

Actually, if you read the Gold-Standard section of the paper you will see its significance as being that, after we abandoned the gold standard, we had NO standard for our currency. Thus, the nation suffered the Federal Reserve’s string-pushing and impotent policies. This is WHY this group of economists proposed the new “standard of stable buying power” for the nation’s currency, and developed a method for its implementation.

As do monetary reformers today.

You raise a couple of MMT points relative to the author’s comments on the benefits of resort TO full-reserve banking. They are irrelevant.

The question that this raises to me, Rodger, is this: do you accept the authors premise for their statement on the benefits of switching to full-reserves, taken from the body:

“”The power of the banks either to increase or decrease, that is,

to inflate or deflate, our circulating medium would thus disappear over

night. The banks’ so-called “excess reserves” would disappear, and

with them one of the most potent sources of possible inflation.””

If you don’t accept that Roger, we can go nowhere. If you do accept it, then you must resist the temptation the next time you are drawn by tradition to say that :

“With full-reserve banking, the banks can still create money.”

Or, “full-reserves and the reserve ratio doesn’t matter because the bankers can go get all the reserves they want.”.

Cause they can’t.

That is what needs to be understood by you, Cal, Neil and ALL the other MMTers. This is NOT our Grandpa’s monetary system we’re talking about. .

Thanks.

joe

LikeLike

Banks can get all the reserves they want, limited only by bank capital. That’s what the discount window is for. More important than the discount window are “overnights” They are overnight loans to banks who need reserves.

My own company used to lend millions of dollars to our bank (then the Continental Illinois Bank) almost every night, and received the money back the next morning. (Banks need reserves only at night.)

A third source of bank reserves is bank lending. The instant a bank makes a loan it simultaneously creates its own reserves.

In short, banks can get all the reserves they need, any time they need them.

Those are the facts. You can continue to disagree, but that won’t change the facts.

I agree that we can go nowhere.

Rodger Malcolm Mitchell

LikeLike

In the debt-based money system of private bank credits created under a fractionally-reserved and capital regulated system , ………YADDA YADDA.

WGAS?

Nuff said for another six months , Rodger.

LikeLike

Take as much time as you need, Joe.

LikeLike

Joe,

Thanks for answering this:

Your answer was, ” . . . all the answers are yes.

Except if #4 refers to government bonds, which would then be a no.There is no necessity for issuing government bonds. “

I agree with your caveat about government bonds. But are you saying, in your “money without debt” system, that:

Bank deposits are not the debts of the bank?

Bank loans are not the debts of the borrower?

Bonds are not the debts of the issuer?

CD’s are not the debts of the bank?

Travelers’ checks are not the debts of the issuer?

Money market accounts are not the debts of the money market?

Rodger Malcolm Mitchell

LikeLike

WGAS, Joe?? I figured out what that is, laughed loud, and I agree with you.

My concern is how the cost of using money affects the economy. My contribution is the idea that as we rely more on credit, the cost of using money increases. I look at graphs comparing total debt to M1 money (at FRED, comparing TCMDO to M1SL or AMBSL) and I can plainly see that since 1947, the debt-to-money ratio has increased significantly — and thus, the cost of using money must have increased significantly.

But I don’t quite get all that out, and somebody comes along and says “All money is debt”.

They might as well say “I insist on ignoring what you are talking about.”

All debt is money? WGAS!

LikeLike

Arthur: I & many others agree that you are doing good work & respect & GAS about what you are saying. But having a novel meaning of the word “debt” in order to exclude “money” does not enlighten.

They might as well say “I insist on ignoring what you are talking about.” No, they might not. Understanding that money is a form of debt means understanding what your blog says better.

Thinking that there is a thing called “money” which is mystically different from “debt” is a major step down the road to bad economics. (Which you have avoided in spite of this fact.) Money is a kind of debt, transferable debt. Thinking about it that way makes it clear that the moneyness of something depends in practice on who issued it. Nobody is saying they are identical. But you have to classify correctly first to understand how moneys differ from other forms of debt, and how say, taxation and loan repayment are instances of the same thing, the “reflux” of credit/debt.

LikeLike

Cal & Art,

As an aside, it was about 60 years ago that a teacher said to my class, “All money is debt.” Of course, I promptly forgot it. Then about 20 years ago the memory popped into my head.

Not knowing anything about Monetary Sovereignty, MMT or anything similar. I simply expanding on that memory by thinking, “If money is debt, then . . . ” That expansion grew to my first book, “The Ultimate America.,” The next book, “Free Money,” was a rewrite.

I first learned MMT existed when Randy Wray saw Free Money and asked me to come down to UMKC to speak to his group. Up ’til then, I actually thought I had invented the concept !!

Anyway, it all began with that short phrase, “All money is debt,” which actually is a tautology. Because all money is a substitute for barter, there is a fundamental requirement that someone owe something to the holder of money, else money would have no value.

Of course, we are a long way from barter now, but the money/debt relationship remains. It’s interesting how a simple phrase can take one on a long ride of discovery.

Rodger Malcolm Mitchell

LikeLike

Somebody way back gave a list of things that he said were money and not debt, including tally sticks.

I read an interesting paper on one of these MMT sites, maybe Mosler or Wray, about the origins of money. Tally sticks were one of the earliest, more formal forms of money. The peper describes how one is created, and how it is broken in half, and by presenting the “creditor’s half” to the debtor, one is entitled to something. The debtor’s half was kept in a safe place, so it could not be “lost”, because in order to be paid off, the creditor’s half had to match up precisely – like matching the rifle marks on a bullet, proving which gun it was fired from.

It was a very clever system, for something so low-tech. Quite an interesting paper.

The tally stick very clearly represented a debt, no doubt about it.

LikeLike

I find it interesting that the Kucinich thing and monetary.org are getting a big following due to the right motive (fix the thing we wrongly fear “US fed. Debt”) but they do it with no real understanding of the current system. They think the system needs fixing, but it is how they think about the system that needs fixing.

They think the US fed. govt. must borrow to spend and this is the root of all our problems.

They then take their own misunderstanding of our current system and propose all types of changes.

If they just said, “stop the requirement of issuing T-securities for deficits”. They would then be able to see the system as it truly is.

They would see that without changing the law this also has to be true: “we currently don’t need to issue treasury securities”.

Which leads to oh treasury securities must then fund nothing.

Which leads to: “Oh, so we already have the system I want, it’s just I and the majority of citizens don’t understand it yet (over 40 years later).

LikeLike

Thanks for recognizing the Kucinich support.

Your train of “uh-oh” thought is kind of cute, but meaningless.

Please explain how WE do not understand the present system.

“They think the US fed. govt. must borrow to spend and this is the root of all our problems.”

The government MUST either borrow or tax to spend. That’s what the GBC is all about, and the cause of our debt-ceiling crisis.

Where is the PROOF that the government does not need to debt-fund its deficits?

But THAT is not the root of all our problems.

WE do say ““stop the requirement of issuing T-securities for deficits”.

Such would end with the passage of the K-Bill.

SEC. 106. ORIGINATION IN LIEU OF BORROWING.

(a) In General- After the effective date, and subject to limitations established by the United States Monetary Authority under provisions of section 302, the Secretary shall originate United States Money to address any negative fund balances resulting from a shortfall in available Government receipts to fund Government appropriations authorized by Congress under law.

(b) Prohibition on Government Borrowing- After the effective date, unless otherwise provided by an Act of the Congress enacted after such date–

(1) no amount may be borrowed by the Secretary from any source; and..””

There is no difference between that and Lerner’s approach to funding the deficit, but Lerner’s approach is not the law. Where is the MMT/Lerner Bill?

Although it is exactly proposed in the Bill, that doesn’t mean ““we currently don’t need to issue treasury securities”. If that were ‘currently’ true, it would not be in the Bill.

Which leads US to conclude that the MMTists are in denial of the legal construct of the GBC on the one hand, and to confirm that we do NOT have the system we want; and to ask the question again to the MMTists – IF the Kucinich Bill passes, what part of the public policy initiatives of economic stability and full-employment would still be missing from the MMT proposal?

Thanks.

LikeLike

It is the game of “Monopoly”, you know the board game that goes on for hours on end that usually ends when someone says “screw this, you win, I’m done”.